Playing Cops and Robbers

Jinho "The Piper" Ferreira grew up in West Oakland, California, during the crack epidemic. Through sports, he found his way out of the violence and drug-filled streets and attended San Francisco State University, earning a degree in Black Studies. At the same time, his hip-hop group Flipsyde was attracting attention and eventually took off, touring the world and fronting for artists such as Snoop Dogg, the Game, and the Black Eyed Peas.

Then in January 2009, standing in the midst of a demonstration protesting the police shooting of an unarmed black man, Ferreira began to consider a truly radical idea: “If people who loved justice enough to protest brutality were not willing to become police officers, then it was highly probable the change we were searching for would not occur.” It took some time, but from that moment, he decided to become a police officer.

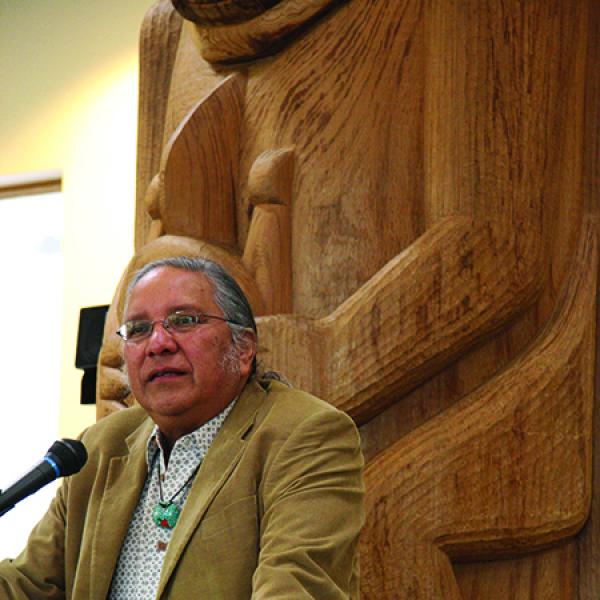

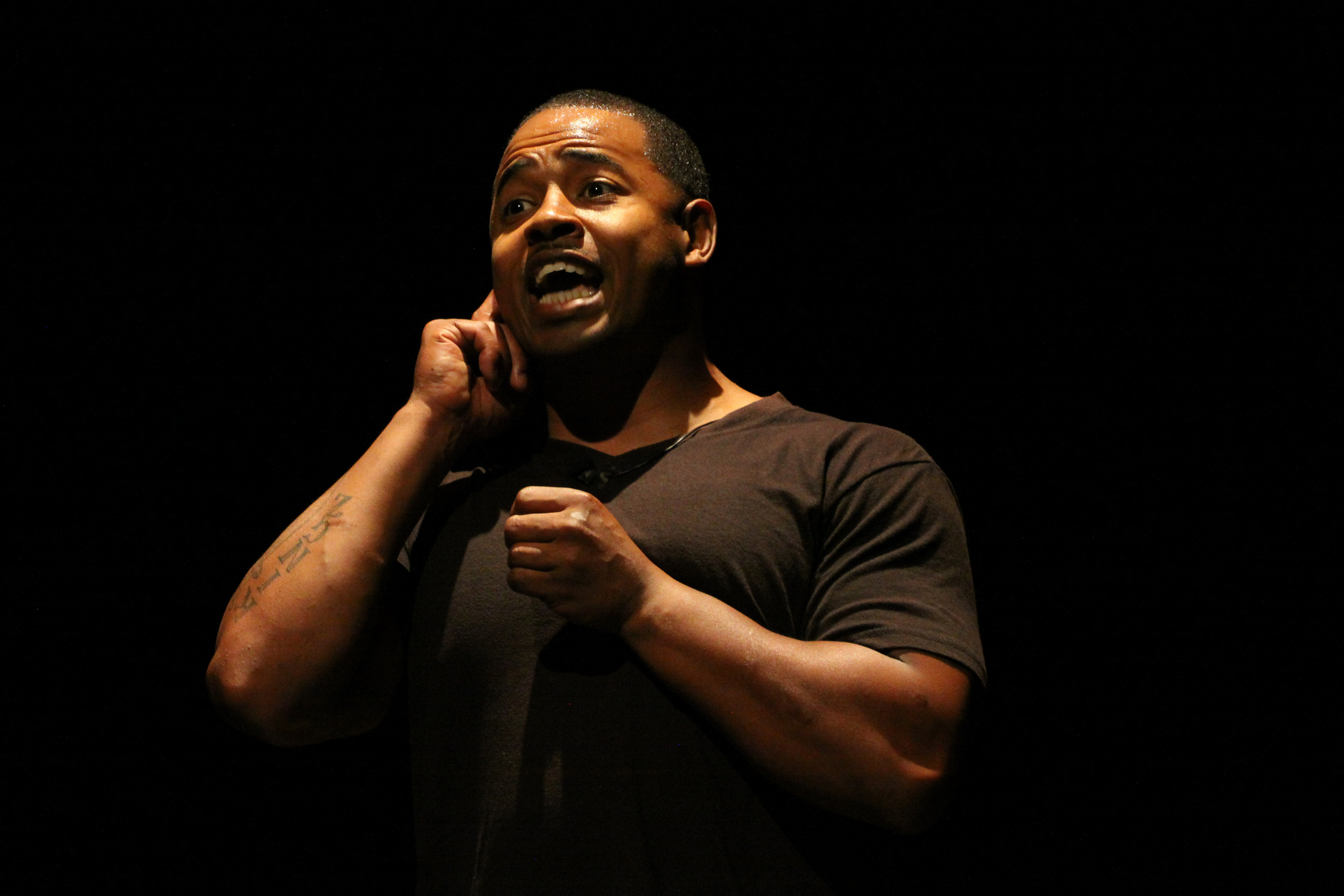

And yet, the arts remain a central part of his life. In fact, his work as a deputy with the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office informs his creativity. In 2014, he wrote the one-man play, Cops and Robbers, in which he plays 17 characters. The play highlights the frequently fraught relationship between police officers, the communities they serve, and the media, and Ferreira played to sold-out shows during the play’s run at the Marsh in Berkeley. Below, Ferreira describes how the play has impacted his police work, and how he believes the arts can move us all forward.

TAKING STOCK OF THE SCENE

When I started [as a police officer], we began having talk sessions with kids. I work in a neighborhood where there are about 37,000 people and about 6,000 of them are ex-offenders with about 1,300 people on probation and parole. I pulled 25 kids into a room and we’re talking about whatever they want to talk about.

But somewhere in the conversation, the thought crossed my mind to ask, “How many of you know a cop personally?” Only two kids raised their hands. One knew a dispatcher; another knew a probation officer. In an area where pretty much every family has a family member that’s been to jail, none of them knew a cop personally. So how could you see the police as anything other than storm troopers coming into your community to take people out of it? That had to stop.

“WHY DON’T YOU WRITE A PLAY?”

I want this world to evolve as much as it possibly can, but it seemed as if everyone was talking past each other. Everyone was just comfortable in their own little silos, preaching to their choir.

I was tired of hearing the same arguments that I heard when Rodney King was beaten. That was 20 years before! It was so depressing, because I’m risking my life every day for change and I don’t want this movement to be wasted. There was just a terrible, intense emotion inside of me. I almost felt like I was going crazy.

I knew I couldn’t fit that [emotion] into a three-and-a-half-minute song. My wife said, “Why don’t you write a play? Just write a play.” I had never written a play before, I had never acted onstage before, but I did it. I wrote the entire thing in a matter of days, the arguments as I understood them. If people could listen to where the other guy’s coming from, at the very least they would be able to strengthen their own argument. So, I got onstage and told everyone what everyone else was thinking.

I began performing. A community-based organization would bring 20 kids to see the play, and sitting next to them would be the chief of police, a city council member, teachers, therapists, probation officers—everyone was mixed in there because everyone’s voice was validated by the play.

It’s not like when you’re riding in the car and you turn on the radio and the guy is stating a political position you don’t agree with, so you turn the channel. When you’re watching a play, you paid your money and you’ve come to the theater. Now there’s this guy stating the position you don’t agree with and you’re all upset, and then in the next five minutes, he’s another character and is voicing what you believe deeply. Then you can compare the two and see how you can strengthen your opinion, or see the parts that don’t make sense and let them go.

|

THE PLAY’S IMPACT

There are a lot of people that I knew before that wouldn’t have even considered attempting to change law enforcement in any way, because they thought that it was unchangeable. Now they’re making strides. They’re making connections.

[Creativity in policing] is thinking outside of the box. Every time you think outside of the box, you’re going to meet with some resistance. But it’s necessary if you want change. We have creative people in law enforcement, and some of them are hesitant to think outside of the box because they’ve proposed ideas in the past that were shot down. But cops are going to listen to cops. The job is so unique that it’s difficult to accept critique or take advice from someone who hasn’t experienced being a cop.

[Developing the play] affected my policing because all of a sudden you have a cop in the newspapers for writing and performing a play about an officer-involved shooting. I had no idea how the higher-ups would react. But I had to make that jump, just like I jumped into law enforcement.

It turned out one of the higher-ups had started a unit called the Youth and Family Services Bureau Crime Prevention Unit, and what he wanted to do was not just fight crime but fight the forces that cause crime. How can we make sure that guys that are in jail are getting the skills necessary to be properly re-integrated into society? If we could create a productive citizen out of that guy that’s just getting out of jail, we’re not just solving a crime today, we’re taking a criminal off the streets for the rest of his life.

He approached me when he heard about the play. He saw it and thought I would be a great guy to get in on the ground floor of building that unit. We created a nonprofit called the Deputy Sheriff’s Activities League where we serve about 3,000 kids in the area for free. We have a state-of-the-art boxing gym. We have basketball. We have about 1,300 kids and about 100 parent volunteers in our soccer program. We have an Explorers program with over 100 kids who want to be cops.

With my arts background, I’ve come here to help some of the kids from time to time. I helped one win a freestyle rap battle down in L.A. I just gave him a little coaching on rapping and then he won first place. A lot of the kids know about my music because it’s all online. I did teach a theater workshop with the kids. Some of them were pretty good. But they know me more as a cop.

WATERING THE SEEDS

I think that music, the arts in general, is an outlet that allows you to express your emotions. If you express your true emotions creatively, then you will find that it’s not just therapeutic for you but for other people as well. A lot of times, as adults, we can do and say things that aren’t productive. But if you allow that energy, that destructive energy, to sit there in you, it’ll rot your spirit away. You even develop health problems. The most beautiful part is when you put those feelings into music, and you find that someone from a completely different walk of life understands what you’re doing, they thank you for expressing that emotion in a way that’s therapeutic to them.

In our society, we’ve been raised to believe that art is separate from everything else. It shouldn’t be. The way that it’s situated, art is on the opposite end of the spectrum from policing and the military, which is nonsense.

In the same way that martial artists combine art and fighting, or dancing and healthy movement for fighting, I believe we could do that intellectually in our approach to law enforcement. Let’s stop the crime before it happens. Let’s be creative and artistic in our approach. We have to water those seeds.