Doing the Coolest Thing

Chris Gerdes might not be reinventing the wheel, but he is certainly reinventing the way we use it. Gerdes is a professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University, and director of the school’s Center for Automotive Research and Revs Program. Together with his team, he studied the brainwaves of race car drivers to develop a car that can travel 150 miles per hour and take hairpin turns—all without a human driver behind the wheel. He is also developing programs that help drivers stay in their lanes and avoid collisions, as well as studying new combustion processes for engines.

Now, he is looking at ingenuity and transportation from an entirely different perspective. Gerdes is the inaugural chief innovation officer at the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), a new position with a one-year term. His mandate? Facilitate creativity within the department, and help it keep pace with innovations like those taking place in his own lab at Stanford. In his own words below, Gerdes tells us about his role at the Department of Transportation, and the creative ways he’s approaching it.

THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX

[At Stanford,] I have a question that I like to repeatedly ask the students, which is, “Is this the coolest thing we could be doing?” One of my colleagues has dubbed that the Gerdes Principle. It’s this need to pull back, particularly as students are working on a PhD thesis. They become very expert in this area. They start to beat their head against a problem. So one thing that I find necessary from the creative side is to pull back and realize, in a university environment, how many constraints we may put on ourselves. Why are we looking at this problem? Is it because we told a sponsor we’d look at the problem? But if there’s a better problem, why don’t we go to the sponsor and say, “Here’s where the value is”?

I think that one of the challenges in government is to get people to think beyond the constraints. We spend a lot of time asking, “What if?” What if we could do anything? The reason this is so important is that a lot of times, the constraints are not as great as they seem. Government is a constrained environment, but the farther that you get away from the actual legal constraints, the more they grow, almost like an urban legend. So there’s this tendency to think, “I can’t do something.” Then as we start to dig into it, it’s like, “Well, maybe we really can.”

So this is something that I’ve been working on—to try to make sure that people think without constraints, and then add the constraints back in.

THE ART OF IMPROVISATION

I think a lot of it comes back to improvisation. I enjoy playing guitar, and enjoy playing music with other people. You go practice by yourself in your room, and then the moment you get together and play with other people, this thing you’ve rehearsed so beautifully—if you’re improvising—no longer fits. It’s too busy of a guitar part to fit with the keyboards, or the drummer’s doing something different. So it’s this ability to think about how I’m bringing something to this, but it has to mesh with what other people around me are bringing. I think that’s just one of the parts of the arts—the encouragement to open yourself up, to stretch and to try things, not knowing if they’re going to work out perfectly or not.

One of the improv techniques I love using here is the “Yes, And” exercise. Beginning every sentence with, “Yes, and...” gets people in the habit of accepting what the other person in this conversation has offered, and then trying to build off that. You get the sense that if I keep trying to bring the conversation back to my thing, and I don’t accept yours, we never get anywhere new. But if I hear you, and I add something, we can get to some really unexpected place, quickly.

The other [technique] I like is called “Word at a Time,” where everybody adds a word as you go around a circle and you try to make a sentence. What’s fascinating about it is that as you’re listening to the words coming, you’re thinking the sentence is going one way, and then the person immediately before you says something totally different. It really sensitizes you to the fact that you’re having the same conversation, and yet the people that you’re having it with have a totally different understanding. Suddenly there’s this need to adapt and reflect that.

Clearly, [the point] is not that you should say yes to everything. But in the idea-generation process, it’s important to have that flow. In government, there’s often the sense that you have to have the idea all worked out before you bring it up. This has people hold back. They’re not sharing, so you miss this opportunity to find the “and” between people’s ideas. It also creates an artificial value on ideas—people are very personally attached to whether their idea is accepted or rejected. It can slow down the process. Whereas in this improvisation, the sentence isn’t going to be perfect, the conversation isn’t going to be perfect, but it’s interesting, and we accept it.

THE ROLE OF CHIEF INNOVATION OFFICER

I’m the first chief innovation officer, and we’re trying a few different things to figure out what works. The first is to promote the culture of innovation within the department. I find that the Department of Transportation has a huge number of innovative people trying new things. And so part of it is to celebrate that, to shine a spotlight on that, and to figure out how those ideas that individuals are generating can propagate throughout the organization.

The second part is to look at where the barriers to innovation exist within the organization and how we can lower some of those barriers.

The third is looking outside at innovation. There’s a huge amount of innovation going on in things like automated vehicles or unmanned aircraft systems that the private sector is leading. [This type of innovation] can really achieve the mission of the department to provide safe, efficient, affordable, accessible transportation. So the question is then, how does the department respond to these things? It’s not the traditional role of, “We’re building the highway,” but we want to encourage that innovation, we want to ensure safety, and we want to ensure access. [DOT Secretary Anthony Foxx] is very focused on making sure that transportation is a ladder of opportunity for people. The private sector isn’t always going to provide that. They will perhaps target the most profitable sectors first.

TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNITY DESIGN

One of the things that Secretary Foxx is very focused on, and really involves innovation, is this ability of transportation to either connect people or to divide people. When you look at the history of the development of the interstate highway system, a lot of low-income and minority communities were devastated as the interstates ran into the cities. So you managed to connect a lot of cities to each other, but you really managed to cut off a number of communities. If you look at some of what was written at the time about these decisions, you realize that a lot of this was deliberate. This was not simply a matter of these communities lacking in political power or voice; there were some actual deliberate efforts to divide them. The secretary has pointed out that we need to recognize this. As we rebuild infrastructure, it's our opportunity to do better.

It becomes a real question of how do you engage communities? How do you get people to understand the possibility of the transportation system to connect or to reconnect? There’s been a wonderful effort, led from Stephanie Jones, who’s our chief opportunities officer, to have design charrettes in different cities, to walk the neighborhood, to get people talking about what their aspirations are, and then to have designers and engineers together in the room, to put their ideas on paper, to sketch it out, and help them realize that.

As an average citizen, if somebody proposes a highway design, you may see the flaws, but how do you propose a different highway design? How do you have the ability to do that? I think that’s a huge area where innovation and creativity can help. How do you give communities the ability to vision their future, to think about what could be, and to do that early enough in the planning process where that can be taken into account? All of the money that we will hopefully be spending to rebuild infrastructure in the coming decades not only provides a good place for cars, but provides the spaces where people will want to gather. It can help provide community centers, and it can help make sure people are connected to healthcare and to food.

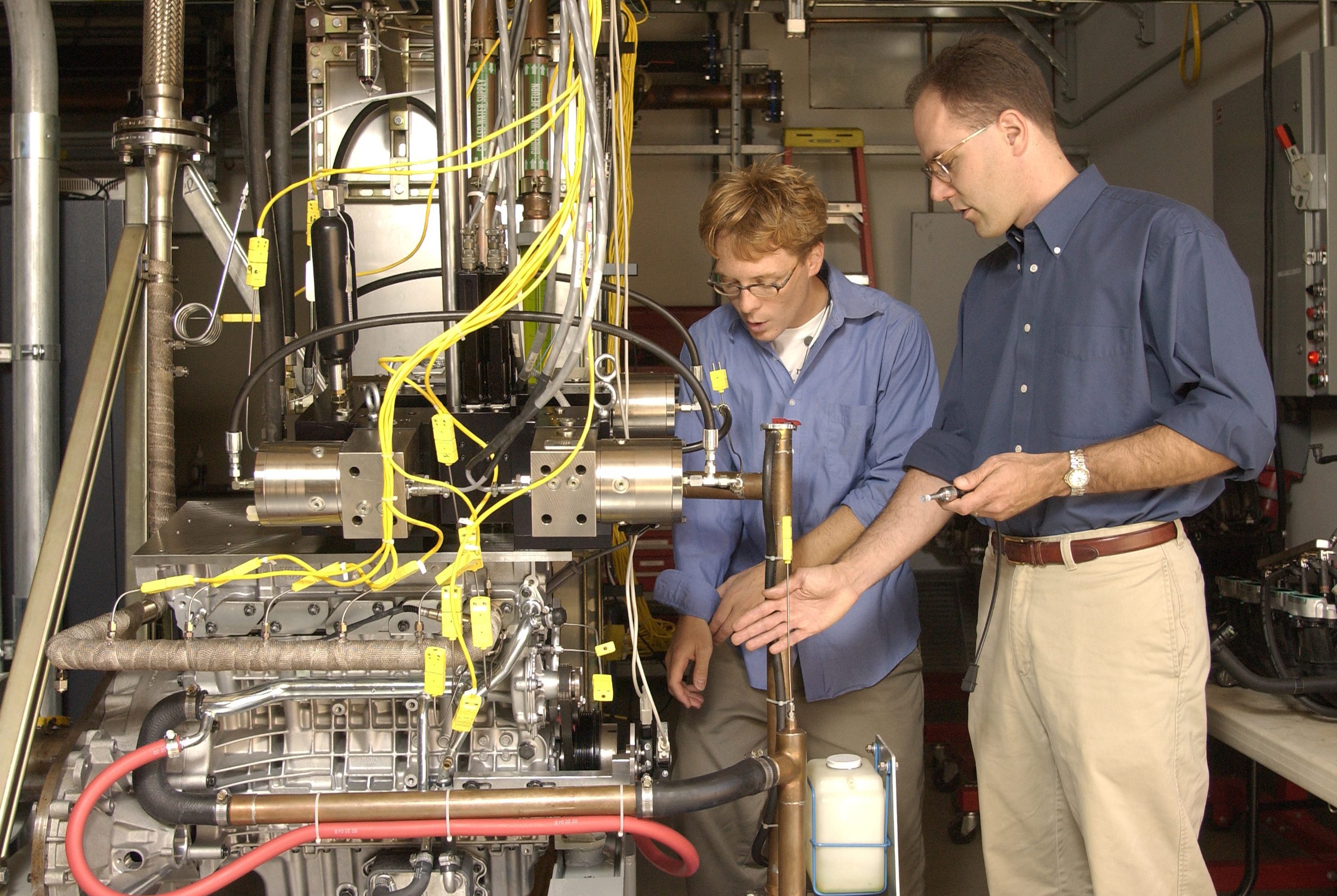

Associate Professor Chris Gerdes, right, and graduate student Matt Roelle employ a five-cylinder Volvo diesel engine to develop a fuel-efficient technology called homogeneous charge compression ignition, or HCCI. Photo by Linda A. Cicero/Standford News Service |

BALANCING CREATIVITY WITH PRACTICAL NECESSITY

[In our lab at Stanford,] one of the things we balance is big-picture, blue-sky thinking with very rapid prototyping. Always take the next step.

I like to use the example of the Space Program a lot. As an engineer and a science geek, there’s nothing more impressive than what came together to put a man on the moon. But from a management perspective, it’s also a huge accomplishment. It was a sequence of missions. The delta between any two missions was not that large, and yet we achieved this great innovation. I think a lot of times, when people hear “moonshot,” they think, “We need to go directly there.” But NASA was smart enough to say, “Not only can we not go directly there, but we need to think in terms of multiple programs that make us smart enough to get there.”

With folks from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, we did a program to have them think about what life would be like in 30 years; to think about the job description that they would be writing six years from now; and then to think about what can they do in the next 30 to 60 days, in concrete fashion, to get smart about these things? So I think that’s the balance. That’s what we always have in a lab: “What’s our big-picture goal?” But then, “What can we put on a test vehicle and try out this week or this month?”