Ages of Discovery

Rob Giampietro's early passion for design was catalyzed by an interest in computers. Giampietro, who is creative lead at Google Design, said that working with design programs as a teenager “felt like playing computer games.” He has managed to fuse these interests throughout his career, bringing together design, culture, and technology for projects in settings from museums and art galleries to public health organizations and New York City’s bid for the 2012 Olympic Games.

Giampietro began his career working with designers Bill Drenttel and Jessica Helfand before opening his own studio, Giampietro+Smith, and then practicing as principal at design studio Project Projects. He has served as president of AIGA NY, the New York chapter of the professional association for design, and was a 2014–2015 Rome Prize Fellow. He currently leads Google’s Material Design studio in New York, along with its design outreach initiatives. He began this role, he said, envisioning how Google could “behave as a cultural institution, alongside behaving as a commercial institution.” Below, he discusses his passion for interactive design, the power of interdisciplinary colleagues, finding balance in technology and the creative process, and the contemporary relationship of science and culture.

BORN DIGITAL

I have been in design my entire life. It has always been a passion of mine, in large part because of my interest in computers. I was part of the first generation that could really use computers to make design. There were programs like PageMaker and QuarkXPress that, to me, felt like playing computer games. I was always really excited about being able to actually make things on my computer, and to do so in ways that would help friends of mine. There was always an inherently social aspect to being a designer that involved being out there in the world, helping projects get off the ground, which I really enjoyed.

I grew up in Minneapolis, and when I was a teenager, the Walker Art Center rebranded. They asked Matthew Carter, later a MacArthur Fellow, to work on the Walker’s new brand. His solution was to design this typeface called Walker, which had snap-on serifs that you could only do with a digital typeface. Within a year, designers at the Walker were using it in these incredibly engaged and subversive ways. It was fascinating to think about what a font could be if it was born digital.

I found that tremendously inspiring, thinking about becoming a designer myself. Many years later when I was at Project Projects, we got the opportunity to design the identity for the museum SALT in Istanbul. The Walker project was very much in our minds, because we were interested in the same [themes] of permeability and change that Carter was interested in. What we wound up doing was essentially making the letters S-A-L-T in the typeface almost like temporary installation rooms in a museum. We would invite typographers to come to Istanbul to draw those four letters, install them in the typeface for a series of months, and then the next typographer would come and reinstall new letters. SALT would use that version of their typeface for everything they made in that four-month period. So you see change over time, and have a typeface that’s programmed the way that a gallery or an exhibition space is programmed.

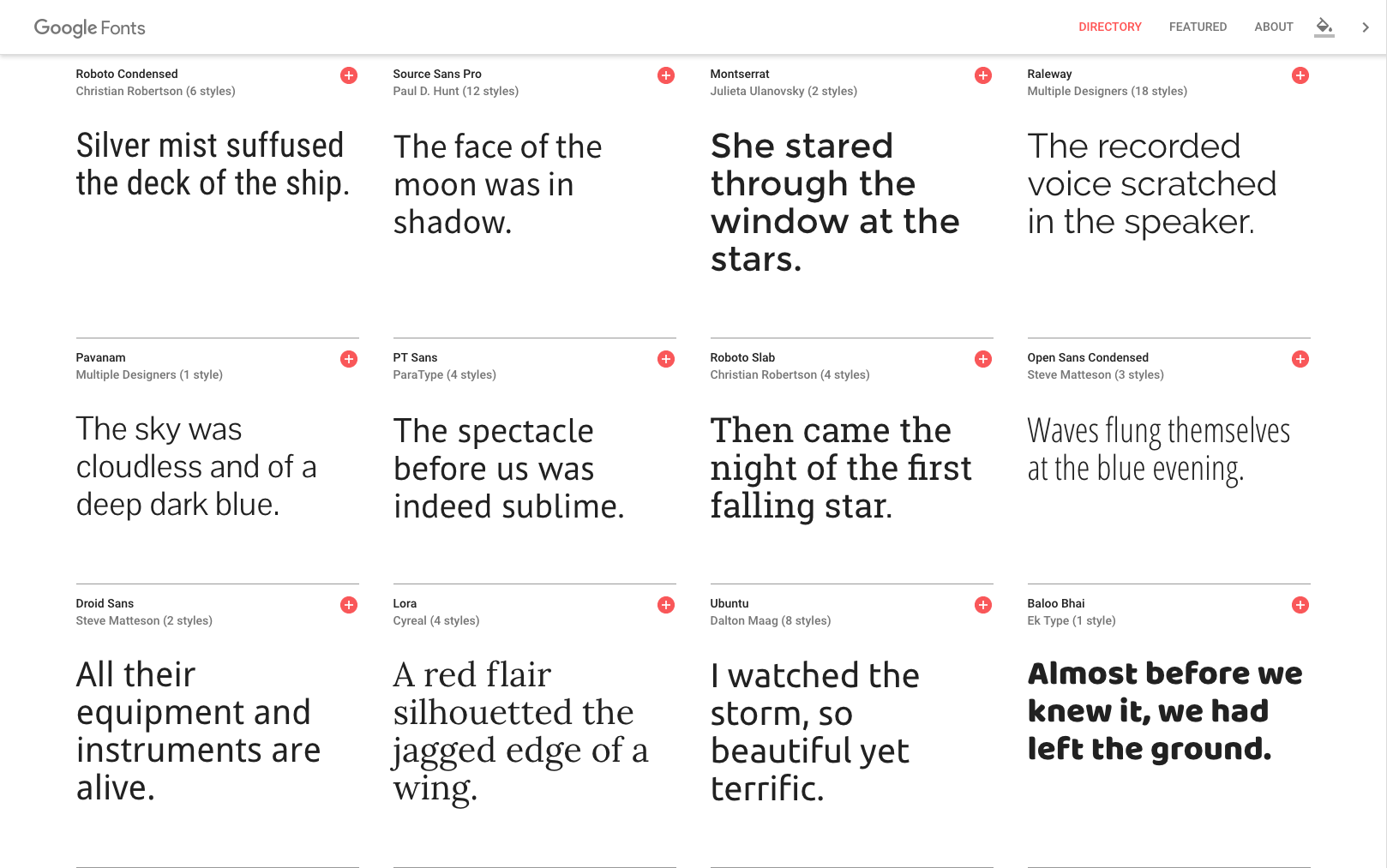

It’s really come to full fruition with the re-launch of Google Fonts [a directory of open source designer web fonts]. It was the first product that I worked on, and it was fun to bring my passion for digital type to Google. Google already had the largest font service on the Internet, and was hosting over 250 billion font views a day, a staggering number. We just hit our ten trillionth font view the other week, and support non-Latin alphabets in over 130 countries. From this small museum in the Midwest that commissioned this very particular typeface at the dawn of digital typography, all the way out to Google being able to make language and expression available to the entire world through that same tool, it really shows the range of what these things can do.

FINDING YOUR WAY

The job I’ve had the longest is being a teacher, at the Rhode Island School of Design for over ten years. I think teaching is the place you go to replenish and reframe your practice, because your students are always asking new questions, and forcing you to relate to them in new ways.

I think it’s really important to learn how a lot of different processes work in general, but also to be a specialist. I think one of the ways you can add value to a team early in your career is to know something really deeply. There are motion designers at Google who are right out of school, and they’re great aestheticians who make beautiful work, but they’re also so valuable for their intensely deep knowledge of the tools that they use. As a young designer, I immersed myself in typography. I remember working on a project with Bill Drenttel and Jessica Helfand to redesign The New England Journal of Medicine, in which we had to give really exhaustive specifications around typographic standards and practice. I saw older designers working with high-level, more abstracted concepts, and it’s tempting to feel like you need to move toward those things in order to get recognition. I think it’s often the people that are intensely detail-oriented who begin to find their way to bigger problems through being able to sweat those details initially. Even if the tools are going to change five times in the course of your career, take the time to learn the tool deeply and use it expertly if you can.

A selection from Google Fonts, one of the first products Rob Giampietro worked on at Google. |

THE POWER OF INTERDISCIPLINARY PERSPECTIVES

Between Project Projects and Google, I won the Rome Prize, and [was able] to go to the American Academy in Rome for an independent project. It was a wonderful opportunity to write and reflect on that city as a design space. [Until that point], I had only worked with all designers in a design office. Suddenly I was sitting with geologists and restorers, painters and composers, and different types of archeologists. One of the things that made going to Google so exciting for me was it really hit all of those buttons that were so stimulating for me in Rome. There’s an aspect of the Academy [at Google], in that it’s really encouraged to follow your passions and to work on the things that will have impact to our users. Within my own team, I work with a couple of writers, a motion designer, with engineers, type designers, and book designers. It’s really a huge range of disciplines. The skill sets are so precise that, really, my job is to help remove obstacles and get out of the way, and encourage all these people to do their great work.

TECHNOLOGY AND THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Authoring something with a group of people at Google is different from doing it for a museum or a gallery as an individual, and I think it’s important to recognize that. One of the guiding principles we have at Google is when we’re applying things like machine learning and using them for creative purposes, we really want that to be aligned to a clear user benefit.

What’s important in the case of any new tool is to really understand your context, and what the possibilities and discussions are within that context. With machine learning, we try really hard to do it in a way that improves the user experience, just as we would any design gesture. Whether you’re making something smoother because it feels nicer in the hand, or you’re applying machine learning to it because it reveals more beautiful imagery, if it’s a design gesture, you should make it with the user in mind. If it’s a mode of self-expression, then you’re not beholden to those same restrictions. In that case, your obligation is really to be interesting and engaging to an audience, and to be true to your own vision of what’s interesting to you about that technology, to ask questions about it.

BRIDGING SCIENCE AND CULTURE

[At Google Design, we hold] a conference called SPAN whose tagline is “Conversations about design and technology” as an attempt to bridge those two cultures. Thinking about ways to synthesize them and bring them together is important. History is very cyclical, and there are times in which culture is dominated by scientific observation, and times where it’s more dominated by aesthetic or artistic observation. It’s not that they’re mutually exclusive, but maybe they’re two oxen in a yoke, where one is pulling more and the other is pulling more at different times in the journey.

We are in a moment where tech is such an important part of our culture that it’s impossible for science not to behave and be super inspiring culturally, in the way that the Apollo missions, for example, might have been in another time. There are periods of history in which there’s great artistic flourishing, and periods of history where there’s great scientific flourishing, and we’re really in one of those periods right now. I don’t think there needs to be as much anxiety about what role science has to play in culture. I think science should just be confident that it is culture, and really move from there.

I remember one of my first weeks at Google, riding home on the subway, and realizing that every single person was looking at their mobile device, and what a cultural responsibility we had to make those experiences great. It’s the same when people looked up at the heavens and started discovering the planets. There are ages of discovery.