Why We Can't Fuhgeddabout It

In 1999, HBO already had a reputation for pushing boundaries with shows like Oz -- which dared to be sympathetic about prison inmates -- and The Larry Sanders Show, a show about the duplicitous nature of the late-night television business. But though the lines between hero and villain were somewhat fuzzier on cable, and cable shows weren't hampered by multiple ad breaks, cable series still looked fairly similar to their network cousins, most of which could be categorized as benign sitcoms or predictable dramas. Then along came The Sopranos. Premiering on January 10, 1999, the show ran for six seasons and amassed a slew of awards along the way, including 21 Emmys.

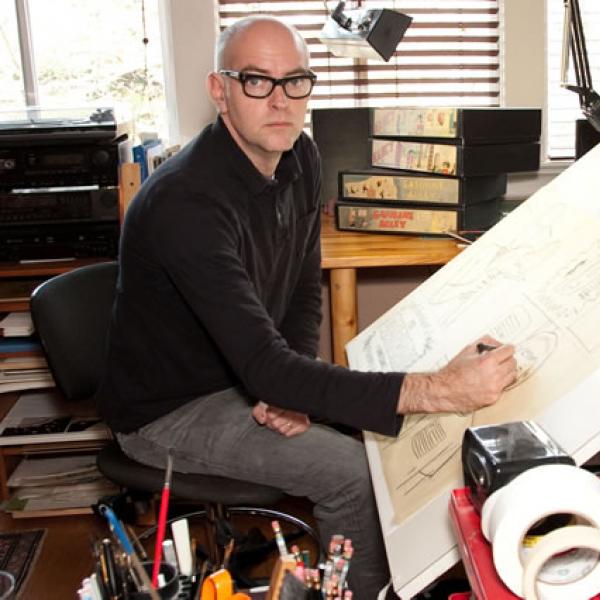

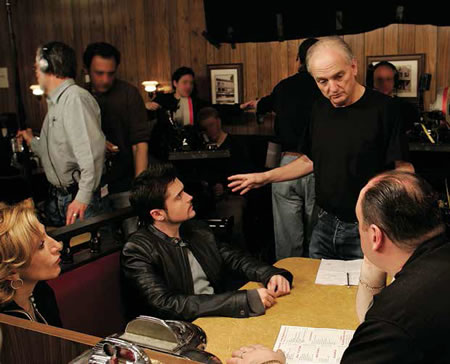

It's difficult to find any media coverage of the series that doesn't include some variation on the phrase "the best-written dramatic series in the history of television," as Vanity Fair enthused in a 2007 feature. The show went on to set a new artistic standard for television, which series like Lost and Homeland have since aspired to reach. Despite what we now recognize as the show's clear artistic merit, veteran producer and screenwriter David Chase (Rockford Files, Northern Exposure), only landed the deal to produce The Sopranos for HBO after being turned down by each of the traditional networks. Chase not only brought a new type of story to the small screen, but he changed the very way in which television stories were told. We spoke with him by telephone to find out what exactly made The Sopranos so groundbreaking.

From Rock-and-Roller to Filmmaker to TV Maker

I was initially interested in rock-and-roll music, and I wanted to be a rock-and-roll singer, a drummer first and then a singer. At the same time, this was early college, I went to school in New York and… I began to go to foreign films. It was there it first occurred to me that a movie was not like a Chevrolet, it was not these things that are produced out in Hollywood, these machines -- which is what they've become.

I saw that there were credits on them and that a movie was directed by so-and-so, and maybe even written and directed by the same person, and I just fell under the spell. I've been under the spell of movies ever since I was little, but [that was when] I thought it was something maybe I could do. I wrote movie scripts and I never sold any. But I did get a chance to write for TV and I stayed in TV and I did okay in TV. But my first goal was to be a filmmaker.

Sometimes a Great Notion

I was working in television, but as I said, I wanted to be in movies, and I thought [the idea for The Sopranos] would make a good motion picture or an interesting motion picture -- a story about a mobster in therapy and his mother who's making his life miserable. This was in the mid-'90s or something. At that time, I was picturing [Robert] De Niro as the mobster and Anne Bancroft as his mother. It turns out later on they went and almost made that movie: they did Analyze This, which is very similar to The Sopranos in concept form. But when I came up with it as a movie, my agents at that time told me, "Oh mob comedies, nobody cares," and, blah, blah, blah. I listened, but I had it in my back pocket. So when it came time for me to do a TV show, I thought, "Maybe [this will] work as a television show since I'm not doing anything with it as a movie."

I may have been aware subconsciously that there was a need in certain parts of the viewing public for something more than they were getting from the networks, something more complicated… something more surprising, something that rolled out at a different pace, something that mixed comedy and drama together instead of keeping them ghettoized.

As a person who wanted to work in TV, there was nothing really interesting that I wanted to work on. And so some part of me thought maybe there's an appetite for this from people, maybe they're ready to just do something different and a little more risky.

On the Appeal of Untidy Endings

As I'm looking back now, [the narrative structure of The Sopranos] all had to do with pace. I didn't want the narrative to unfurl at the kind of pace at which I was used to working. I wanted the story to unfold much more slowly, or maybe even more quickly. I just didn't like that pace of network television. And so in trying to tell a story at a different pace, it kind of affected the things [like] not necessarily tidying everything up at the end.

The chronology's interrupted -- it has to do with time. I think something in me was chafing under the scourge of network time. In other words there were 42 minutes in a [television] hour, not an hour. There were 42 minutes and the rest of it was commercials. I wanted to do something where I wasn't sharing any time with any other stories, with any commercials. I wanted to do a pure television show that didn't talk about Tide washing machine products or anything like that and didn't distract you from the essence of the narrative. I wanted to do that -- that's more like a movie. That is a movie.

When I started seeing foreign films, or films by people that I hadn't really heard of before as a kid, like Orson Welles or even Hitchcock -- if you look at his endings, they're not tidy. And that was something that appealed to me a great deal -- the lack of tidiness. I don't mean that Hitchcock isn't a very tidy man -- he's very tidy and very tight -- but at the end of Vertigo, for example, what is he really saying? I think he's saying a couple of things whereas at the end of The Sound of Music, they're saying one thing. Or at the end of an episode of Magnum, they're saying one thing: they caught the guy.

Using Soundtracks to Extend Narrative

As a pure audience member, as somebody who just went to the movies on a Saturday afternoon or went to the drive-in movies on Saturday night, I don't really think I noticed [the music] very much. I mean, I'd heard of Otto Preminger and [people] like that, but it never really clicked for me that movies were the work of an individual or a group of individuals, and it never really clicked for me that the music was playing while things were happening. But once I started getting into music, I started getting into rock-and-roll music, I started thinking about how rock-and-roll music could be used in movies. I wasn't the only one, obviously. Martin Scorsese was there a long time before me and once I saw that he had [used rock-and-roll in movies], and Dennis Hopper did it in Easy Rider, I began to pay more attention to the music, because I was listening to that music more than I did the scores of [instrumental composers]. The [instrumental] scores to me were kind of inaudible. But using a song by the Byrds was not inaudible to me, because that I related to.

Was I trying to extend the narrative? I was probably trying to amplify it or nail it down or give it a roundness, give it an overview…. That's what I started to feel was possible. At the same time, other people were doing it too. Stanley Kubrick is another guy who doesn't use orchestral scores; he uses existing music. And that's the way it was with The Sopranos.

I very seldom planned anything around a song. No narrative was planned because of a song. Maybe a couple of times, but mostly they were not. The shows were written, and then the song was decided afterward because you could change the feeling of the show by the song you ended it with. You could change the meaning and the feeling. So I wasn't extending the narrative, but I was extending the artistic process, the process of creating narrative. I was extending that by the choice of song.

The Future of Television

I think cable TV is the wave of the future… If you're talking about network television, where does that need to go? It needs to go where it's always needed to go and never has gone, which is taking the risk and the chance that you might insult somehow, or offend or horrify or surprise someone. Once you're relieved of the job of selling Volkswagens, you don't have to be worried that Volkswagen's going to be angry at you because you lost a few customers because they didn't like the episode you did about gay marriage. So then you can do anything you want. In other words, cable television, they're just selling Mad Men, or they're just selling Game of Thrones. Game of Thrones is going to exist or not exist on its ability to gather viewers. And if Game of Thrones does an episode in which some falcon is slaughtered and a certain number of people in the animal rights organization are going to say, "I'm never going to watch this show again," that's only the problem for Game of Thrones. It's not a problem for General Motors or Bristol Myers or anybody else. The product just has to work on its own.