Mixing Words and Pictures

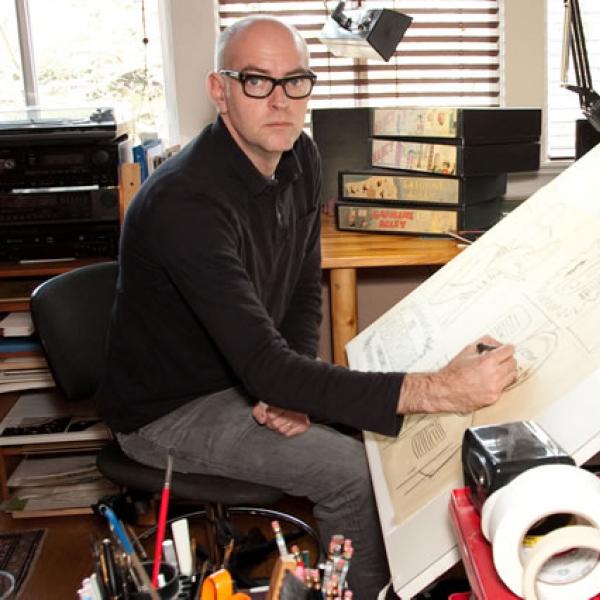

For much of their history, comics have enthralled kids and adolescents with cheap, pulp tales of superheroes and villains. And yet, despite their popularity and often-intricate illustrations, they were always considered to be entertainment rather than art. Things began to shift during the underground comic scene, when cartoonists such as Art Spiegelman began to push the boundaries on what could be held within the rectilinear panels of a comic strip.

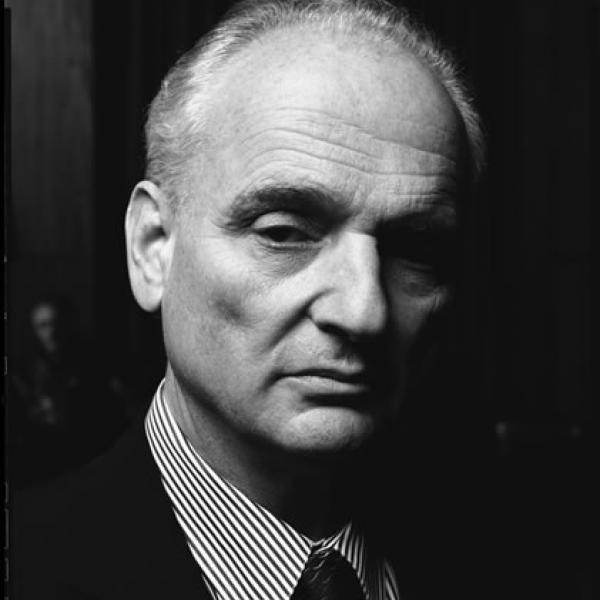

Then came Maus, which tore away whatever artistic boundaries may have remained. Serialized in Raw magazine and published in full in 1991, Maus was arguably the first critically acclaimed graphic novel, and established Spiegelman as the man who helped elevate comics into an art form. The two-volume work is a cartoonist's account of his parents' lives as Polish Jews during World War II, featuring Jews portrayed as mice, Poles as pigs, and Germans as cats. Part history, part fiction, and part memoir (Spiegelman's father was an Auschwitz survivor), Maus became the first graphic novel to win the Pulitzer Prize, and laid the groundwork for what has become a unique genre in its own right. Here is Spiegelman, in his own words, on the evolution of comics.

In the Beginning

The first [comic] that imprinted itself on me was Mad. I even did a sequence about it in my book Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! where I can barely read. I'm with my mother in a drugstore. I pick this thing up. I open it and it was like this was a like a secret message from the gods, and I had to have it no matter what response my mother had to this thing. And then I studied it like some kids studied the Talmud, as the punchline to that sequence goes.

At about the age of 12, a book called Comic Art in America by Stephen Becker [was published]. That book was really important to me—despite it being incredibly error-laden—because there were pretty much no histories of comics. Comics haven't had a history until recently. So I'd see these things and it'd be a little window to this impossible world and I'd want to know more about it. That got me to start going to libraries and living in old newspaper stacks, which were still bound volumes rather than microfilm reels, and pursuing those comics I liked and copying them. Copying all of this stuff was part of what makes one a cartoonist. It was the equivalent of a comic school. I see an ear can just be a little half-circle with a line it, or it can be a backwards three inside that—all the different vocabulary marks of what comics are were part of that exploration.

It never occurred to me that comics were anything other than worthy. They were in fact among the most worthy endeavors I could imagine. They were how culture got introduced to me, more than through other media…. I always assumed they were a container big enough to hold whatever I could hold.

The Underground Scene

My comics got stranger and stranger. There wasn't any obvious place to present or publish such things…. [They] were tending toward surrealism and stuff that can only be called experimental—a comic that didn't have to worry about the obvious forms of communicating either a gag or a suspense story of some kind. That had me puzzled about what I was up to.

[My first magazine Arcade emerged at] the moment where the economic realities of comics were shaking. The work was interesting. It was getting somewhat less interesting as it got more and more focused on sex and drugs…. the field was sort of bottoming out a bit. And with an underground cartoonist I was very close with in San Francisco, Bill Griffith, I started Arcade as a kind of lifeboat for what we thought was important about our scene with the hopes of turning it into a quarterly newsstand magazine.

I moved back to New York [from San Francisco]…. There was nothing going on in New York. It wasn't like a cluster of artists where in retrospect, San Francisco felt like Paris in the ‘20s. People came from everywhere because that's where the underground comics were happening. In New York, everything was much more organized around trying to appear in the existing magazine structure. There was, again, no place to publish the kinds of things that I was interested in.

It was in that world of underground comics seeming more and more predictable that Raw grew up because [my wife Françoise Mouly] naively said, "Let's do a magazine!" I had enough, thank you, after Arcade, but she dragged me into this thing because there weren't any other prospects…. Everybody in the book had a certain degree of real ambition of making comics that hadn't been like anything made before.

The Faustian Deal

At that point I figured it was time for the Faustian deal, meaning comics were still a mass medium, but not as mass as they used to be. Therefore one had to set up a situation where comics could be invited into museums, bookshops, libraries, and universities. Then we could get grants just like poets do who aren't in the commerce business. That was a very specific articulation that developed in the period when we were starting Raw. It was at that time that I was applying to places like the NEA and [New York State Council on the Arts] programs and meeting no interest whatsoever. I remember I was applying for some grant to work on Maus. Invariably in these attempts, I'd be told, "Well, you can't apply in the drawing category. It's got writing. You can't apply in the writing category. It's got drawing. I guess we put it in mixed media."

What's interesting about comics is they really are a separate medium for anything else…. They're their own medium that synthesizes these two different strands of expression and ties them together. Every great comic is the result of finding a new cocktail for how these things fit together.

An "Amazing Distillation"

I think of comics as a kind of amazing distillation. One's allowed only a few words, and relatively few marks to make the picture compared to oil paintings or something that's more overtly visual. You're forced to strip it down just by the nature of what it is as a medium. One of the attributes that I like in comics is how things can be distilled to their furthest point, and then re-expand once they hit your brains through your eye. So the process is one of distillation, and it's usually seeing how efficiently one can make something incredibly inefficient and complex, like an emotion and a thought, happen.

For me, every strip has its own need to look a certain way, whether it echo the modernist adventure of the '20s, the Cubist look, something that looks incredibly grotesque, or something that looks more streamlined and modern. Each strip had its own needs.

The Making of Maus

I had done a three-page comic strip called Maus in an underground comic calledFunny Aminals back in '72. That made a bit of a stir in so far as within that small teacup there could be a stir. I knew I had made something that wasn't like other things. It was rather different than the longer version of course, but it already was, by underground comic standards, quite sober. I knew I was working on something that was important to me and that people could respond to.

I returned to the three-page Maus and was expanding it, partially because I just moved back to New York. I had to be in touch with my father anyway, and a microphone would be a handy defense weapon. I started doing this in no context whatsoever, just thinking it would be interesting to make a very long comic book that would need a bookmark and ask to be reread.

During the ongoing interviews with my father, I was trying different ways of drawing, and at the same time, without thinking about it, making these very rough sketches to indicate the panel breakdowns and how much language would fit in a panel and how the pages might structure themselves. Eventually it became clear to me that the problem with drawing this large size and bringing it down [to scale] was that it was a way of minimizing the personal errors, and thereby giving oneself extra authority as the artist…. The sketches I was making felt much more vulnerable. All of my mistakes were at full size. I didn't like seeing the work blown up, because then it magnified the mistakes. The problems that that style brought up had to do with clarity. It was also important with a story this complex that I not get in the way by [causing somebody to] stare at it for a long time to find out if that was a foot or a tree. I had to eventually synthesize something that looked like my first sketches but had the clarity of a typeface.

What [the success of Maus] has been like for me is it's led to images like being chased down a corridor by a 500-pound mouse, walking in the shadow of an Easter Island-sized statue of a Vladek Maus…I got, in some ways, both the benefits and the trap that came with a singular work that's admired…. It would be like some blues musician, and then all of a sudden you have this blues song you did that's playing behind a Lexus commercial, and wherever you go for the rest of your life, they want to hear that three minutes.

Comics as a Medium

A critical mass was reached, not when Maus first came out but within ten years—critical mass meaning enough work that critics would have to pay attention to it. The weight that comics could achieve was present. It was the culmination of that Faustian deal.

Now it's something one can slow down and consider as a medium, but the full range of what's available, possible, and can be made in comics is now probably flowering like never before in the history of the medium…. As a result, the people drawn into making comics come from a more sophisticated gene pool of people who have a wider set of options often, and the readers are not only ones who can't read books without pictures.

[Comics are] now firmly enough entrenched that they're going to affect all future making. Because the conventional wisdom might be right, which is that we do live in a more visual culture, and therefore for information to come at us visually and be able to decode those visuals is kind of urgent. Comics have the advantage of existing between the two languages so that they'll stand still long enough for you to contemplate them rather than be part of the laser-beam barrage, and that gives them a certain potency.

The Terminology of Graphic Novels

The respectability that came with the phrase "graphic novel" is a thoroughgoing annoyance to me, because it leads to books that are made to be studied in academia, and that's no less of a marketplace than making comics to appeal to 12-year-old boys whose prepubescent stirrings are beginning and they have to be titillated with action and sexualized images.

It's a great marketing term. What I called Maus while I was working on it was a long comic book that needed a bookmark and has to be reread. I don't think that that would make a great subtitle for a category for a library or a bookstore…. In general, if there is a need for the phrase, it's because people are embarrassed to read comics, but they're not embarrassed to read graphic novels. They even get hipness points for it.

I'm fine with the word "comics" even though it's a total misnomer, but it's the misnomer that got there first. I've been spelling it "co-mix"…Comix with an X was what the underground comics were called because they were X-rated very often. And if you mispronounce it "co-mix," then you get to mix together the words and the pictures and you have something that's actually sort of accurate and belonging to its roots. But I'm not pitching for another marketing term…. Whether I like it or not [the term "graphic novel"] is useful, because it communicates to people the notion of an ambitious work that stirs words and pictures together. Me, I just call myself a cartoonist, and I'm making co-mix.