The Making of Lost Freedom: A Memory

Dalton Wells Internment Camp in Utah. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society

As composer-in-residence at the Moab Music Festival, Japanese American composer and musician Kenji Bunch performed a piece he wrote for viola that completely captivated festival cofounder and music director Michael Barrett. The piece was named Minidoka, after a place in Idaho where one of the Japanese American internment camps was located in the 1940s. Barrett had recently learned that the Dalton Wells internment camp had been located about ten miles from Moab, Utah, and an idea began to form.

Barrett proposed that Bunch expand the piece to create a chamber music piece, and Bunch jumped at the chance. Barrett then reached out to actor, author, and civil rights activist George Takei who, with his family, spent four years in two Japanese American internment camps. Takei agreed to become the narrator for the piece, and Bunch and Takei immediately began collaborating on a work that shines a light on what life was like in camps such as Dalton Wells. Funded in part by the NEA, the project culminated in September 2021 with a performance of this new work for string quartet and a narrator, titled Lost Freedom: A Memory. Takei and Bunch talk about creating the work.

GEORGE TAKEI’S STORY

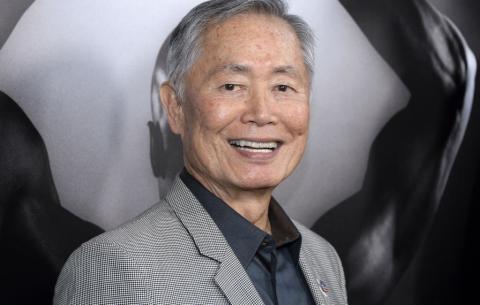

Author/actor George Takei. Photo courtesy of George Takei

On December 7th, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, and the terror of that bombing swept across the Pacific to the West Coast, and it rolled across the country to the East Coast. The next morning, President Franklin Roosevelt declared war on Japan, and for us Japanese Americans, the terror intensified. We’re very familiar right now with Asian Americans being assaulted and spat on. Well, that’s what began happening to us. There was no charge and no trial; our crime was looking like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor.

Right after Pearl Harbor, young Japanese Americans rushed to their recruitment centers, like all young Americans, to volunteer to serve in the U.S. military. This act of patriotism was answered with a slap on the face. They were denied military service and categorized as enemy aliens. We were born and raised here, and yet that’s the category they assigned to all. Approximately 120,000 of us were rounded up and imprisoned.

I had just celebrated my fifth birthday, and it was a few weeks after that when my father rushed into my bedroom that I shared with my younger brother, Henry. He dressed us hurriedly and told us to wait in the living room while our parents did some last-minute packing. And so my brother and I, with nothing to do, were standing by the front window just gazing out at the neighborhood. Suddenly we saw two soldiers marching up our driveway carrying rifles with shiny bayonets. They stomped up the porch and with their fists began banging on our front door. It felt to us like the whole house was trembling. My father came rushing out of the bedroom and answered the door, and literally at gunpoint we were ordered out of our home. That morning is one that I will never be able to forget.

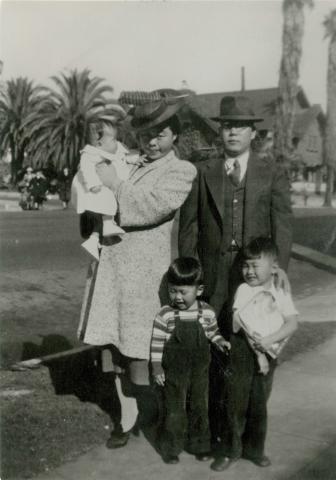

Takei family in the 1940s. Photo courtesy of George Takei

We were loaded onto trucks that morning and we were driven down to Little Tokyo, the Japanese American community in downtown Los Angeles. We were let out at the Buddhist temple there, and the area was crowded with other Japanese Americans who had been picked up. There was a row of buses, and we were tagged and loaded onto those buses, and the buses took us to the Santa Anita racetrack and there we were unloaded and herded over to the stable area. Each family was assigned a horse stall, still pungent with the stink of fresh horse manure. That’s where we would sleep temporarily while the camps were being built. For my parents, going from a two-bedroom home with a front yard and a backyard, to taking their children into a horse stall to sleep was devastating. My father told me about it when I was a teenager, and said it was absolutely horrific, humiliating, and degrading. The government at that time called it a Japanese neighborhood, or relocation center, but it was really a prison camp.

We were incarcerated from 1942 to 1946. From Santa Anita…we were taken to the swamps of Arkansas, to a camp called Rohwer, which, from my childish point [of view], was a magical place. I try to capture that in my narration for the piece that will be premiered at Moab.

I’d never been anywhere like the swamps of Arkansas. Beyond the barbed wire fence was a bayou, and trees grew out of the water. I had no idea trees could grow out of the water, and the roots snake in and out of the water. It was a fascinating thing, and for the new chamber music piece, I talk about the little black wiggly tadpoles that I could catch at the edge of the bayou and put in a jar and see. I’d look at them every morning when I got up, and one morning they seemed to have grown bumps on their sides, and the next morning the bumps looked more like legs, and the next morning the tail fell off and they escaped from my jar. They had magically turned into frogs.

A year [after Pearl Harbor, the government] realized we had a wartime manpower shortage and they needed us, but their dilemma was how to justify drafting people out of a barbed wire prison camp. They came up with what they called a “loyalty questionnaire.” Question number 28 was one sentence with two conflicting ideas. It asked simply, “Will you swear your loyalty to the United States of America and forswear your loyalty to the emperor of Japan?” We didn’t have a loyalty to the emperor, but the government arrogantly presumed that we had an existing inborn racial loyalty to the emperor. So if you answered that part of that one sentence “No,” meaning, “I don’t have a loyalty to the emperor to forswear,” that “No” applied to the first part, “Will you swear your loyalty to the United States?”

If you were willing to bite the bullet and answer “Yes” to, “Will you swear your loyalty to the United States?” that “Yes” applied to the second part of the very same sentence [and] meant you were confessing that you did have a loyalty to the emperor. If you answered “No” you lost; [if] you answered “Yes” you lost. My parents answered “No” as truthfully as they could, and for that they were considered disloyal, and they had to be transferred to the Tule Lake camp [in California], which was bristling with military armament.

Forty years later, there was a campaign by Japanese Americans to get an apology and redress for that egregious violation and incarceration. Congress formed a commission, at which I testified in 1981 and 1988, and my testimony, in part, is going to be part of the text of this chamber music piece at Moab.

REFLECTIONS FROM COMPOSER KENJI BUNCH

Composer Kenji Bunch. Photo courtesy of Kenji Bunch

When Michael [Barrett] mentioned he had worked before with George Takei, it was a sort of pipe dream to me. “Wouldn’t that be cool to work with George Takei?” That’d be awesome, but I didn’t really expect anything to come of it. Then things just seemed to line up, and now it’s happening. Sometimes I have to pinch myself. I could listen to George talk for hours and be enthralled. If I can help in the telling of his story with music that I write [to] access people’s empathy and sense of humanity, that’s my role here—to help humanize the story.

I really focus on the fact that he was just a little kid, because…regardless of our own backgrounds, every adult was a kid, and at some point all of us have felt vulnerable, scared, and confused. George and I [have about 40 years apart in terms of age but we] share the experience of being Asian American. This is George’s story clearly, but I also have a connection to that.

I think a lot about transgenerational trauma. My dad grew up in poverty, and my mom grew up [in Japan] in wartime. Those were both intensely traumatic events, and they were around at a time when trauma wasn’t really recognized and dealt with in a direct way. The upheaval in the last year-and-a-half of both the intense racial justice movement with Black Americans but also the resurgence in anti-Asian hate brings up a lot of this inherited trauma. George will say [that ever] since there have been Asians in America, there has been discrimination, bias, and hate. We both feel it’s really important to tell this story.

The fact that this project has been recognized as something worth supporting by an institution as important as the NEA is huge. It shows that this is a story worth hearing and that this was real. Look at what’s going on in education today with this crazy panic about the way history’s taught. Stories like these are essential for all of us to understand and to be able to connect to emotionally. That’s my job.