The Suburban Canvas

For much of its existence, American suburbia has been considered an architectural wasteland. From shopping malls to McMansions to residential developments, suburbs from Connecticut to California look eerily similar and share a similar pattern of quick, cheap construction that has left little if any room for thoughtful design.

But with the recent foreclosure crisis and growing environmental concerns, new opportunities have emerged to re-imagine the suburbs into sustainable, architecturally innovative communities. Although the other art forms examined in this issue have fully established themselves, suburban design -- traditionally the realm of profit-driven developers -- is only now beginning to emerge as an artistic field. Fueled by exhibits such as the Museum of Modern Art's Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream and Dwell magazine's Reburbia Design Competition, architects and designers are beginning to explore what the suburbs could potentially look and feel like. We spoke with several architects who are leaders within this growing trend, and are quite literally designing new artistic possibilities for all those "little boxes on the hillside." In their own words, here are some of their concerns, projects, and visions.

JUNE WILLIAMSON

An associate professor of architecture at the City College of New York, June Williamson is co-author of the books Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs (2011) and Designing Suburban Futures: New Models from Build a Better Burb (2013). She also served as jury coordinator for the Build a Burb competition, which sought to re-imagine possibilities for neglected or underutilized spaces on Long Island, New York.

You're socialized, in studying architecture, to reorient yourself to cities and the urban environment. But there was always this nagging interest in what was happening in the vast territories that I was taught weren't the concern of architects; that was the concern of production builders. It was business; it was product. It was commercial work.

I think we've moved past prominent architects doing projects that take this ironic stance about suburban commercial development or residential development. There's a much more earnest and engaged dialogue from academics to students, who are interested in this stuff and understand the impact that it can have on their own lives, on their parents' lives, on their children's lives. They get that and are energized by it. I think the development community, in part because of the big blows of the recession, understands that they need to do things differently. They have to be creative about financing. They need to be more cognizant of the impacts and benefits of what they propose. All of that is promising for bringing creative thought to the table and being less formulaic.

A lot of creative people who grew up in these environments and had questions about them are seeing the decay or lost investment in some of these properties. [They are] scratching their heads about what that might mean and what those places could be. It's interesting to see photographers and other kinds of artists, who have a much more nuanced view, I think, of the positive and the negative in these places [imagine new possibilities for the suburbs]. It's stimulating.

There are so many ways in which design can optimize the use of whatever square footage you have in your home. One of the things we emphasize in Build a Better Burb, which is really taking off across the country, is the opportunity to enable second units or accessory dwelling units. [I believe] you should be able to do whatever you want with a house, if you want to carve out an apartment for your adult child or your elderly parents or to rent out to somebody and make a little extra money in an entrepreneurial way or to help you with the mortgage.

Then there's the whole issue of how you use your yard. They could be used with more xeriscaping [landscaping that conserves water] or landscaping of native materials with habitats for wildlife, for growing food. There are all sorts of interesting opportunities there.

Culturally, we need to move past the kind of obsolete, oppositional constraints that it's city versus suburb. We're all knit together in the metropolis, so there's a metropolitan mindset that needs to emerge…. I think design has a significant role to play, both in visualizing this cultural shift to help people better understand the data and the trends and be optimistic about it, to building structures and projects that can demonstrate how it can be done.

PAUL LUKEZ

Paul Lukez is the principal and founder of Boston-based Paul Lukez Architecture, and has taught architecture for 20 years. In 2007, he published the book Suburban Transformations, which highlights ways to develop suburbia into sustainable communities with unique identities. He puts these ideals into practice through his design consultancy Transform X, which uses digital mapping tools to chart a community's evolution over time.

One of the things that's lacking in the suburbs is a sense of space. Everybody does their own thing. They build an object, and their object doesn't relate to another object, nor does it relate to the landscape. It tends to be a very flat world.

What we try to do is create a more three-dimensional relationship, both in relationship to other buildings and the landscape, but also in the Z-axis. So as you're moving up and down through a building, you get different vantages of the landscape, of your neighbors, of [other] buildings. A richness develops, and variety, that wasn't there before.

I think in general there's a greater awareness of the power of design in the public. People are becoming more educated about and aware of the different kinds of options that are available, and that design is an important part of life. Particularly as they start looking around their own environments, people begin to wonder, "How can we improve it? How can we make it better?"

The role of public space becomes really important. Those places that we have to go, whether it's restaurants, whether it's stores, whether it's libraries, schools, places of work -- all those places share a public realm. How those are designed individually, and how they relate to one another, creates a network, both physically and as an experiential network. The stronger those networks are tied to each other as memorable experiences, the bigger the impact they will have on our consciousness. There are many things that we can do to make those really memorable places. We can integrate the landscape in ways that are pleasing, that stimulate our senses. We can create places that are pleasant to work in and to live in. We can create places that encourage social interaction or opportunities to see other people. There are ways in which we can create and form and shape community that can enhance the human experience.

Bigger is not always better. I think the future is about building smarter, more intelligently, and being aware of what we're doing in a way that's connected to the landscape, to our communities, and to our daily lives.

SHANE COEN

Based in Minneapolis, Shane Coen is the principal and founder of the landscape architecture firm Coen + Partners. Coen's work was featured in the Walker Art Center's exhibition Worlds Away: New Suburban Landscapes, and his award-winning designs for the Jackson Meadow and Mayo Woodlands communities have been lauded for their sensitive integration of natural and man-made elements. Jackson Meadow, discussed below, is a residential development in Marine on St. Croix, Minnesota.

[In Europe,] the importance of architecture and design is integrated into the educational system and it's not in ours, anywhere. You don't have somebody that teaches you how to see, and to look at things and to ask questions on why it's beautiful and why you like it and why you don't like it -- our society tends to not think about it at all. I think the type of developers that were attracted to the suburbs weren't interested in design. It was a profit-driven mission that I would group in there with the fast-food movement. Fast-food and malls and housing were all about speed and how much square footage you could offer for less money.

[For Jackson Meadow,] our philosophy was that if we create a sensitive, artistic development, community will actually be partially created because we're going to attract people that care about these issues. And that happened.

The architectural concept was based upon the Finnish architecture of the region; a modern emulation of the Finnish architecture. [The houses] are very contextual and meaningful to the region, and are respectful of the heritage, but they were adapted to the times.

We used a lot of glass; the natural light is invigorating to your daily life. You literally feel like you're connected to the outdoors at all times -- the same with the detached garage. You get to walk to your front door instead of entering your house through a laundry room, and [can] experience your house the same way everybody else experiences it. But you also create space between your garage and your guest house and your main house, so you get a cluster of buildings that is more reminiscent of rural architecture, in a modern way.

Even as a landscape architect, moving into my house out there for the first time was something I'll never forget. Everywhere I turned and everywhere I walked, I was connected to both light and the outside. I still feel like I'm on vacation 12 years later.

[In the future,] I hope that planning is contextual to the land. Most suburbs were planned in an office; they weren't planned by looking at a piece of land and figuring out what that land was really telling you to do with it…. Certainly, I believe, once you move outside the [inner suburban] ring that a public, connected open space system should be a requirement of all suburban development. The land is going to continue to be developed over time, there's no way around it. If we don't focus on it, we're just going to repeat what's already been done.

BING THOM

Born in Hong Kong and based in Vancouver, Canada, and Washington, DC, Bing Thom founded Bing Thom Architects in 1982. A recipient of the Order of Canada and the 2011 RAIC Gold Medal in Architecture, Thom has led the design of residential, commercial, and cultural projects across the globe, including the new Arena Stage in Washington, DC. One of his latest projects is the Blairs Master Plan which will guide the transformation of a nondescript, 27-acre apartment and retail property in Silver Spring, Maryland, into a vibrant, pedestrian-friendly community. Below, Thom discusses the project plans, which were unveiled in February 2013.

I think one of the great problems of suburbia is that the family retreats to this little patch of green space, but they are all isolated. So many social problems occur in suburbia because families are isolated. This isolation is very bad for building community values. I am a strong believer of having people living closer together, but sharing more public space and more open space. It creates a society that is focused on sharing common values rather than protecting private space. We've had this legacy for 50 years now, of families being balkanized and retreating back into their hermetically sealed units.

The new generation is breaking out of that. There is a yearning for being together more and sharing more. They have smaller private space but more public space, and in the end, the social life is better.

[The Blairs Master Plan] is trying to consolidate the emerging town center that is already at Silver Spring. Silver Spring is kind of off-centered; [the town center] is only on one side of the transit line. The Blairs property, on the other side, did not complete the coalescing of this transit node as a major center.

We have created a design that allows people to drift through the Blairs property on their way to the transit station. It's kind of unprecedented that a developer says, "We want to welcome the community to walk through our property." So rather than creating your typical gated suburban community, this project is acting as a very interesting conduit to the transit station.

We provided a significant number of townhouses, which I think would be very good for young working couples with young children. It's an alternative to the suburban house. Of course, the whole idea is of 24/7 activity. So it's not just vacant green space, but it's green space that is active and vibrant on weekends and evenings.

We're trying to create a different kind of town center than your normal suburban town center that is geared toward automobiles. This one is geared toward cyclists and car-sharing. We actually are under-building the amount of parking in the area significantly to encourage people to use bicycles. This way we allow children to cycle, we allow people to walk, we allow people to be together more easily and therefore sustain the communal spaces better…. I think this is a growing trend, which is a very, very good thing.

I think life is about accidental collisions, accidental meetings. Discovery comes from accidents. You go out on the street and you meet ten new friends or you meet somebody you haven't seen in 15 years. You can't do that as well in suburbia because there just aren't as many accidental collisions. But also [in a well-designed suburb] collisions with the natural world become better. When you have a tighter mix of concentration then it's easier to get out to nature. It's the quality of space rather than the quantity of space.

TED PORTER & MERI TEPPER

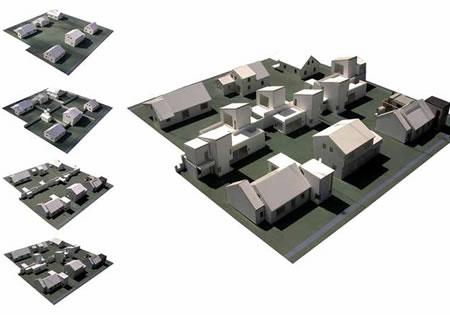

Ted Porter and Meri Tepper practice with Ryall Porter Sheridan Architects, a New York City-based firm that focuses on sustainable design for homes, apartments, and institutions. Recently, several members of the firm were part of a winning proposal for the Build a Better Burb competition, which invited architects to re-imagine possibilities for suburban Long Island. The proposal, called "Sited in the Setback: Increasing Density in Levittown," explored the possibility of building accessory dwelling units on existing suburban lots. These units, or "granny flats," would be able to accommodate aging parents or caregivers for elderly residents, or could be rented out as an additional source of income. Below, Porter and Tepper, who led the project, discuss the rationale behind the concept.

TED PORTER: An inherent problem is the isolation you can experience in suburbs, especially as you age and are not able to drive. That's happening increasingly across America.

MERI TEPPER: There are a lot less options for people who are retiring and want to age in place. There is not enough housing choice for people to live in the same neighborhoods to support their parents, or if you need a caregiver to be with you full-time. The housing choices in the first-ring [suburbs] are forcing people to leave their homes even if that isn't their interest…. And for children who decide they want to move back to the same community they grew up in, the housing choice and affordability isn't there anymore.

[The Build a Better Burb] project, as a primary zoning question, challenged the notion of the rear yard setback where the fence line basically has created the six-foot wall. What if you could redefine the rear yard setback as a place where you could have the option to place an accessory dwelling unit? It would be the choice of the homeowner how that would be developed. But looking at pre-fabrication as a system for construction would minimize site work and disruption.

PORTER: In a nutshell, the goal is to increase density in an existing neighborhood. Through those increases in density, you have the potential for income properties, for families to reunite, for caregivers to be there, for communities to develop, all of these positive attributes.

TEPPER: I think…that most people would welcome the freedom to develop their land to maximize the potential of it economically, socially. It obviously depends on localities, and it would have to be a zoning decision.

PORTER: Before, suburbs developed out of a fear of economic diversity or racial diversity or ethnic diversity. I think that's broken down a lot in terms of race and ethnicity -- not completely but a great deal. But they're still very homogenous economically…. That would be something that this project would help with. If you had small accessory apartments behind your home that you could rent to younger people or older people, then you would change the [economic] diversity of the neighborhood. And I think that would make suburbs better places for everyone.