Military Veteran, Artist, and Art Therapist Peter Buotte Shares Significant Works from His Artist Journey

Peter J. Buotte, MFA, MPS, ATR-BC, is a lifelong artist whose career intertwines visual art, military service, and participatory art experiences for communities. Buotte’s journey includes 26 years of combined active and reserve military service in the U.S. Army, culminating with eight tours overseas, five in combat.

Buotte is currently one of 11 art therapists in the U.S. Department of Defense and the only art therapist that is a combat veteran. He is part of the Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network at the Intrepid Spirit Center/ TBI Clinic at Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center in Fort Cavazos, TX, where he has worked for the past seven years. He leads art therapy sessions with a clinical approach of strength-based cognitive processing. “I create a safe, supportive space that gives active-duty service members permission to explore creatively and therapeutically," he said.

“My early artworks seem to show a formative identity as a therapist. In many projects, I worked conceptually with individuals and groups,” Buotte explained. “I’ve since realized that this was preparing me for individual and group art therapy sessions. Artistically, curiosity drives creativity, and clinically, the art intervention drives the therapeutic effect.” Buotte’s work has been featured in individual and group exhibitions across the U.S. and internationally. We asked Buotte to discuss eight key artworks that have been meaningful in his journey to becoming an art therapist.

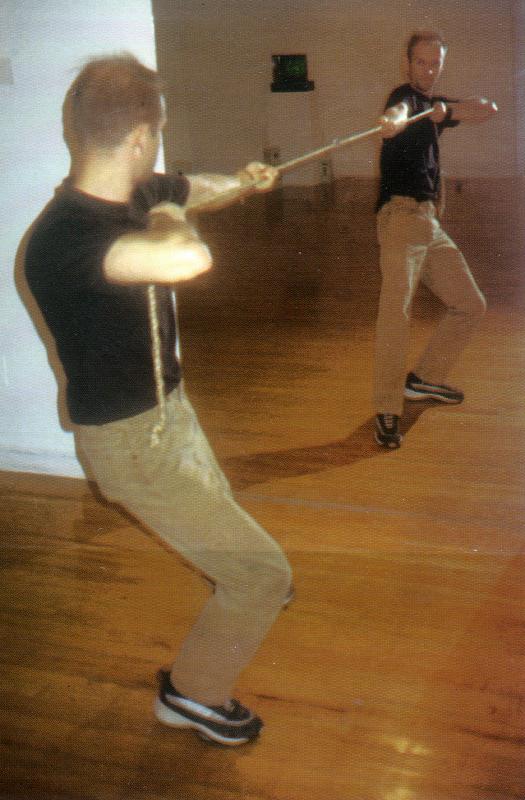

Self Struggle, 1999

Self Struggle, 1999. Photo courtesy of Peter Buotte

This interactive sculpture included a full-length mirror with a hole drilled into the mirror about chest high. There was a rope going through the mirror and anchored behind the wall. It was constructed so that you could have a tug-of-war with yourself. On a piece of paper next to the sculpture, I invited visitors to anonymously write their personal struggles. This was my first substantial sculpture; it opened up new approaches to future artworks. I was offering self-examination and a physical interaction with the art. This work was completed while pursuing a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts at the School of Visual Arts in New York City.

People Puzzles, 2001

People Puzzle installation, University of Maine at Augusta, 2006. Photo courtesy of Peter Buotte

People Puzzle, in process in the studio, 2001. Photo courtesy of Peter Buotte

People Puzzles are modular, changeable, figurative mobiles. They are made with large sheets of extruded polystyrene home insulation. I originally made them to address September 11. I had visited New York and left two days before the tragedy happened. When the buildings fell, it was tragic; even more tragic were the people who decided to jump. The floating, flying figures of the sculpture are based on that event.

Subsequent sculptures became an opportunity for collective work. As a visiting artist at the University of Maine at Augusta, student artists created their own figurative silhouettes to best express their identities. One participant traced herself in a yoga position, one included his skateboard, two did dance poses, and one was in a skiing position. The group assembled the sculpture in the campus student space. It seemed they were trying to find group harmony and balance.

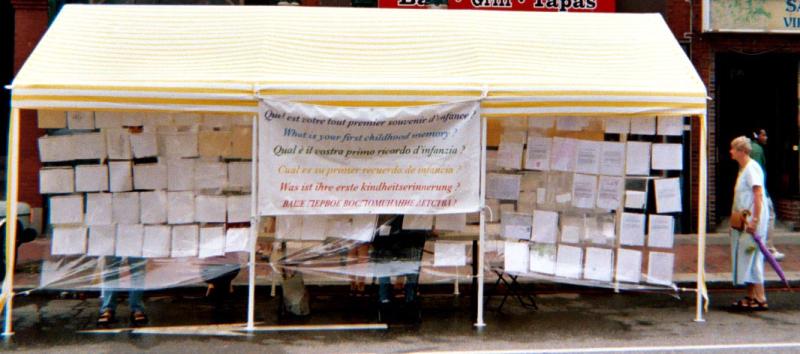

First Childhood Memory Project, 2002

First Childhood Memory Project, public installation in Portland, Maine, 2002.

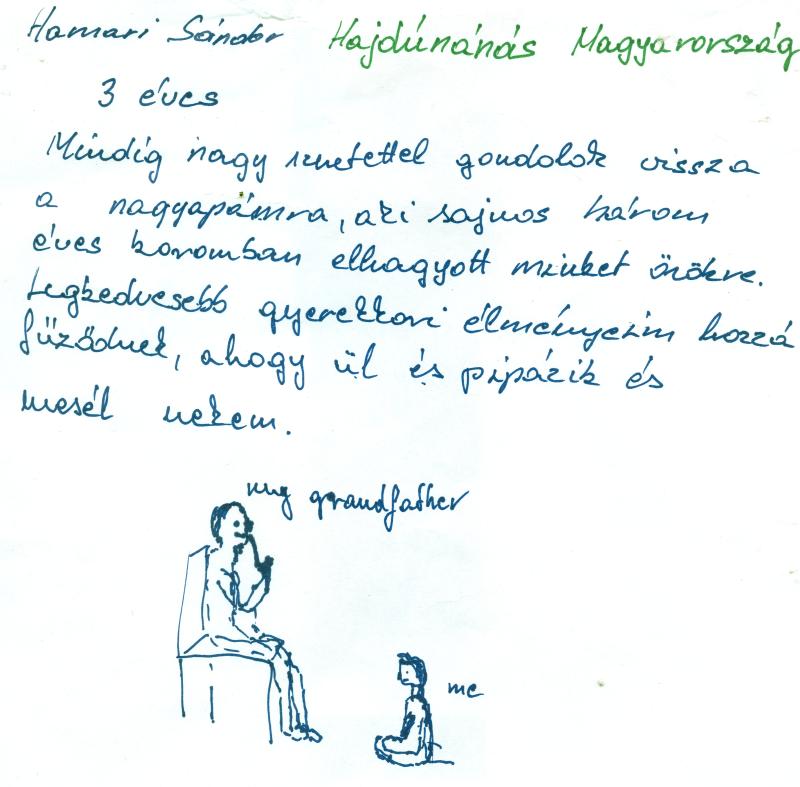

Artwork that includes a memory written in Hungarian in First Childhood Memory Project.

First Childhood Memory Project is a 10-year project that collected and installed over 600 written and drawn childhood memories in 35 different languages.

It is based on my earliest childhood memory and the feeling of separation anxiety I had at age 2½. My mother was leaving to go to university in her car. I was crying. My grandmother, who was babysitting me, said, “Peter, she'll come back.” I didn't believe her. Years later, I drew a picture of this early experience.

This memory made me wonder, “What is the first event in other people’s minds?” I asked my immediate family to draw theirs. It was so fascinating that I then asked cousins, other family members, and friends. It became a social initiative with anyone I encountered. I’d explain the project and simply ask, “What is your earliest childhood memory?”

I studied at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris in 2000. I hung a banner in multiple languages inviting people to submit their memories. I also placed a mailbox at the main entry. In addition to humble sketches, there are memories written in Polish, Russian, Greek, Chinese, French, Somali, and 30 other languages. These memories are drawn on envelopes, paper plates, cardboard, and sheets of paper. When shown in gallery spaces, more memories are written, drawn, and immediately added to the ongoing collection. This project allowed entry for a wide range of people to participate.

Grenade Head, 2005

Grenade Head, digitally milled aluminum, 2005

Grenade Head is a self-portrait milled from a block of aluminum. It is a visual response to my first tour in Iraq in 2003. It is also the first foray into digital art rendered from a scan of my head. Threaded on top is a detonator fuse from a training grenade. It was a challenge seeing the impact on Iraqi culture, government, economy, and families living there. This sculpture allowed me to visually speak about frustration with the situation.

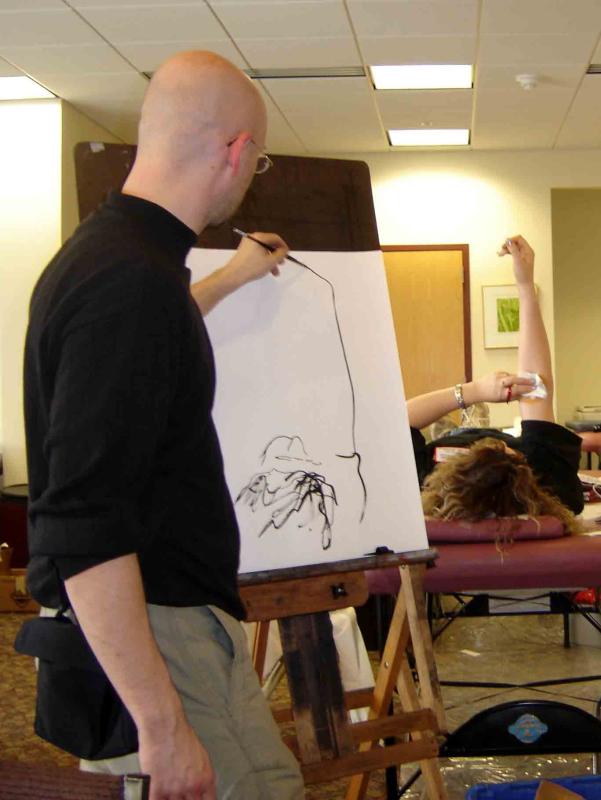

Drawing Blood, 2006

Drawing Blood, 2006. Seen here is a drawing session during a blood drive in memory of Peter Buotte’s mother.

Drawing Blood was a public service that merged a figure-drawing session with a blood drive.

Prior to my return from Iraq, my mom had been diagnosed with stage four uterine cancer. She had already had surgical removal and radiation treatment. Upon arriving home, she was in the process of starting chemotherapy. I got to be her caregiver for six months. I just stayed home with my mom and made art, processing my combat experiences and her health condition.

While receiving chemotherapy, Mom would typically receive a blood infusion. Having been a blood donor for four decades, my mother became the face of all the anonymous recipients. She was hospitalized for the last two months of her life. I asked her, “Can I organize blood drives in your name, in your memory?” And she said, “Yes, dear.”

With the help of two radio stations providing free public service announcements, I organized two concurrent blood drives at college campuses in Maine. During each event, artists created portraits of the donors, making them visible while still anonymous. By the time they finished giving blood, they also received a portrait. Art was becoming therapeutic for me. It helped process loss and enabled me to grieve in public.

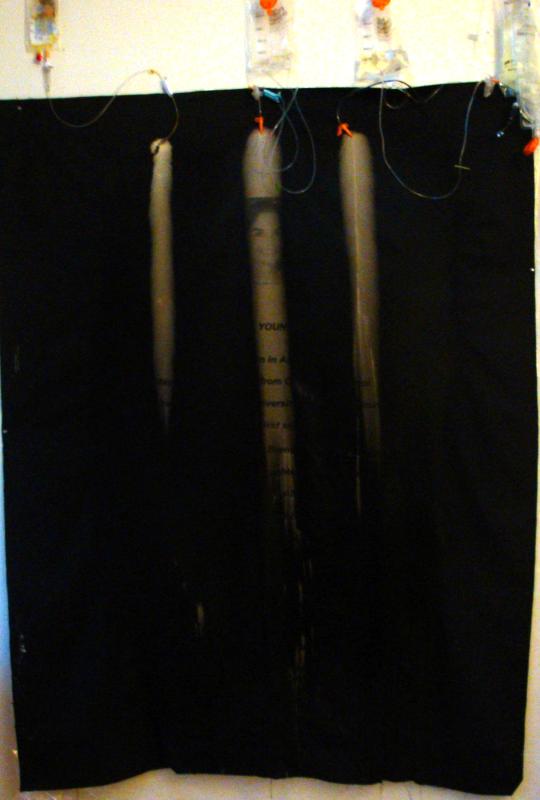

Bleeding Canvases, 2008

Bleeding Canvases, silkscreen on military medical stretchers, 2008, on exhibit at the School of Visual Arts Gallery, New York City.

Detail of Bleeding Canvases, 2008

Bleeding Canvases are self-performing sculptures that make themselves.

From my first day in Iraq in April 2003 to the end of my second tour in 2008, over 5,000 American military forces had passed away in the combat zone. These sculptures memorialize this collective loss of life. I was able to find a list of all of them chronologically, along with rank and branch of service. The information was silkscreen-printed onto both sides of each military medical stretcher. The silkscreen ink matched the color of the olive-green fabric, so names were not perceptible or readable. I also wanted the medical stretchers to stand upright.

As an attempt to infuse life, the intravenous (IV) tube is an important symbol. During the opening night, we let them drip. As the canvases were infused by the IVs, the fabric blanched, and the names were revealed slowly over time. In a way, I figured out a way to keep their memories alive.

Bleeding Canvases were exhibited at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) Gallery in New York City. During the exhibit, a woman asked, “Have you ever thought to become an art therapist?” That woman was Deborah Farber, chair of the SVA Art Therapy Department. She encouraged me to apply. I started the program in 2010.

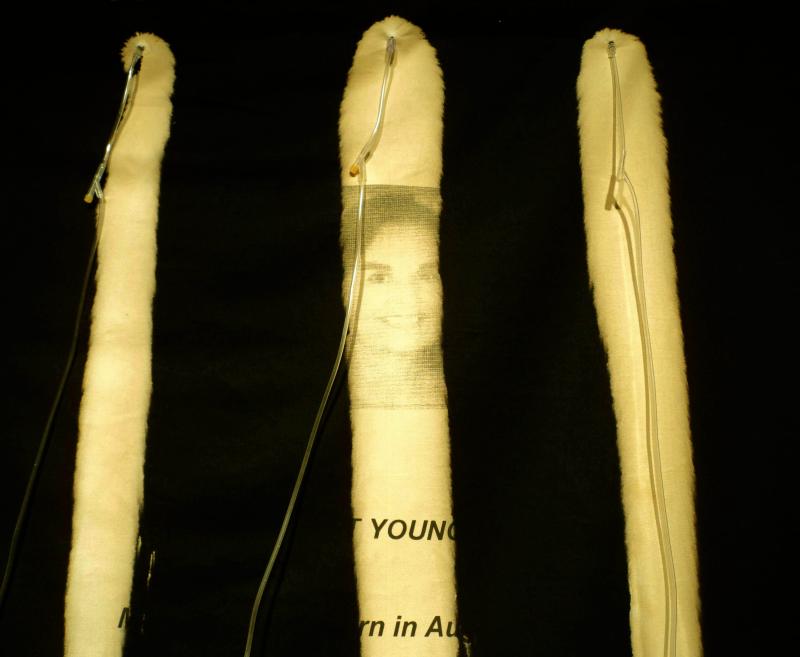

Memorial to my Mother, 2009

Memorial to My Mother, infusion into silkscreened text and image on canvas, 2008.

Detail of Memorial to My Mother, infusion into silkscreened text and image on canvas, 2008.

After creating Bleeding Canvases, I figured out how to symbolically process grief and loss. I decided that I could finally honor my mom. Memorial to my Mother is a work that creates itself using IV bags, and it addresses losing my mom to uterine cancer.

I had three large black canvases silk-screened with my mom’s obituary in black ink. My mom was getting morphine in her final days when she was in pain. I saved her IV bags. I took one of those I saved and, in my own apartment in New York, attached her IV bags, three of them, and for an hour, I just let them gently drip and slowly run out. That was my process to figure out how I could use IV bags to create. And I just cried the whole hour as they ran out, and it was wonderful. The IV bags were used to reveal her obituary.

After this experience, I stepped back and wondered how I could apply what I had learned. How can I be ready for others and handle their mourning, grief, and loss beyond just an individual scale but on a complex scale? In my group art therapy sessions, service members choose processing grief and loss as their number one therapeutic goal. The process of creating two pieces of art that allowed me to process my own grief prepared me for the next step to becoming a therapist.

Spirit of Survival, 2008-present

Spirit of Survival, pigment-impregnated ceramic on granite base, 2022, part of an ongoing digital sculpture series.

The Spirit of Survival sculpture series was conceived during my second tour in Iraq and continues today. My lead question for this project is, “How can the deployed military experience inform art-making?” My mind went to sculptures of ancient Greek and Roman warriors, which are often incomplete or broken sculptures without names or stories. This project will work in the space of continuing to honor contemporary warriors, not as heroes nor as victims, but as people who carry visible and invisible wounds.

The first phase of this project is Invisible Wounds, which features digitally scanned heads of service members who experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injuries (TBI). I asked a formation of service members at Fort Belvoir, “Who would like to be a sculpture?” I then took a group of ten service members to an advanced scanning site. The prompt to each of these service members was to “consider your current physical and mental state and make a facial expression of it.” Each participant was circled by an array of 96 cameras, and with a press of one button, 96 pictures were taken at once. The digital images were then sewn together into three-dimensional sculptures.

Each sculpture has its own military Pelican case. It’s very common parlance that things in the military are transported in these heavy-duty cases. Each sculpture is mounted on granite. In this first phase, I wanted to deal purely with the non-visible wounds ... TBI and PTSD.

The next phase of the project will feature American veterans who are also burn survivors and amputees. The participants have selected their poses for the sculptures. Two people who are missing one leg have decided they are going to be each other’s supporting leg. Without their prosthetics, they are going to be on their own natural leg and then a missing leg in the middle, connected arm in arm, which is incredible. Another person who is on one leg is going to carry a medicine ball, and he will be posed like Atlas, the Greek god of strength and endurance, carrying the world on his shoulders.

Another person competes in the shot put in the Paralympics. We will photograph him as the Discobolus Greek sculpture, the disc thrower. This version will now be the Discobolus in the wheelchair. With this phase of the project, we’re updating Greek sculptures through these athletes and warriors and merging history.

In the fourth phase, I plan to go back to Iraq and work with an Iraqi sculptor. We will scan Iraqi survivors who have PTSD, burns, and amputation. I intend the work to say that PTSD does not discriminate against gender, rank, branch of service, or country. It’s an equalizer.