Deaf Republic

Overview

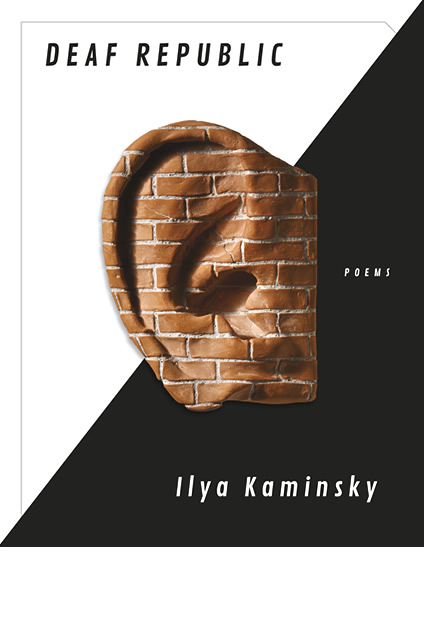

Born into a Jewish family in Odessa in 1977, Ilya Kaminsky grew up in the former Soviet Union, now Ukraine, where he lost most of his hearing because of a misdiagnosed case of the mumps. He left for the United States when he was 16. Deaf Republic, his critically acclaimed second poetry collection, propels the reader forward through a harrowing story in two acts that opens with the shooting of a deaf boy in a public square by occupying soldiers. In protest, the townspeople go deaf, organizing their dissent through puppetry and sign language. A work of “profound imagination” (New Yorker), Deaf Republic is a “cutting-edge, sweeping drama” (Washington Post), "a book of small graces, of resistance, of inordinate, unconditional humanity" (Sewanee Review). "A visit to this republic will not leave the reader unchanged” (New York Times).

“The deaf don't believe in silence. Silence is the invention of the hearing.” — Deaf Republic

Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press, 2014) opens in the fictional town of Vasenka during a military occupation. Public gatherings have been forbidden, and an unnamed occupying force sweeps the city for signs of insurrection. When soldiers breaking up a protest kill a deaf boy, Petya, the gunshot becomes the last thing the citizens hear—they have all gone deaf. In that communal silence, Vasenka’s townspeople invent their own sign language, some derived from existing linguistic traditions, and some governed entirely by illegibility: the need for a language unknown to their authorities. Illustrations of signed words and phrases punctuate the book, offering readers both translation and reprimand: like the occupying soldiers of Vasenka, we are not fluent in their language of dissent.

Primarily structured as a two-act play, Deaf Republic renders a country as a stage and its citizens as its chorus. The first act of the play follows Sonya Barabinski, Vasenka’s best puppeteer; her newlywed husband, Alfonso; and their soon-to-be-born child, Anushka. Together, the Barabinskis lead a rebellion among Vasenka’s people, teaching sign language and arranging silent protests in the town square. Yet, Deaf Republic seems to suggest, a revolution is as much about the private as it is the public. Across Act One, Kaminsky sketches the quiet details of a shared life, small moments that become universal in their intimacy: the press of a palm to a thigh; the smell of familiar shampoo; the shock and jest of slipping on a wet floor; the sounds that disappear when someone dies; the red socks that remain behind, ironed by someone who loved them. In the second act, puppet theater owner Momma Galya takes on the mantle of the rebellion. Poems describe Galya and her puppeteers teaching signs to townspeople, caring for Anushka, tearing through town on bicycles and kissing on park benches. By night, they lure soldiers one by one to their deaths behind the curtain of the theater. Then arrests begin, and the allyship of the townspeople begins to weaken. As Act Two comes to a close, silence, which functioned initially as a form of rebellion, becomes a failure to act. And like translation or a stage, even those shifting forms of silence are a kind of fiction.

“And when they bombed other people’s houses, we / Protested / But not enough / We opposed them but not / Enough,” offers the collection’s first lines in the opening poem titled “We Lived Happily during the War” (p. 3). Situated before the dramatis personae (list of main characters), the poem lives outside of the world of the play. Instead, “...it shows a different kind of so-called happiness, the happiness of living with our backs turned—ignorant bliss,” Kaminsky writes. “The poem is meant to serve as a wake-up call; to prevent people from reading Deaf Republic as a tragedy of elsewhere. Deaf Republics, with their hopes, protests, and complicities, are everywhere. We live in the Deaf Republic” (Slate).

- While most of the poems in Deaf Republic are contained within Act One and Act Two, there are two poems that bookend the collection: “We Lived Happily during the War” (p. 3) and “In a Time of Peace” (p. 75). Why might Kaminsky have chosen to set these two poems outside of the play structure? How would your reading of the book have changed if those two poems were not included?

- The soldiers who march into town and the townspeople of Vasenka both have a shifting relationship to each other’s language. The soldiers arrive “speaking a language no one understands” (“Dramatis Personae,” p. 7) and the townspeople of Vasenka invent their own sign language: some of the signs derived from various traditions (Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, American Sign Language, etc.). “Other signs might have been made up by citizens, as they try to create a language not known to authorities” (Notes). In Vasenka, how is language used to resist? How is it used to oppress? Can you apply this to language that you encounter in your own life?

- In the first poem of Deaf Republic, “We Lived Happily during the War,” Kaminsky repeatedly invokes the idea of houses. “And when they bombed other people’s houses, we / Protested / But not enough,” “I was / In my bed, around my bed America / Was falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house—,” “In the sixth month / Of a disastrous reign in the house of money” (p. 3). How would you describe the different meanings of “house” in this poem? When you consider your own “house” or household, who is included? Who is not?

- Throughout the book, Kaminsky frequently uses metaphors and similes to describe a scene. For example, “spectacles shining like two coins” in the poem “As Soldiers March, Alfonso Covers the Boy’s Face with a Newspaper” (p. 12), or “our men, once frightened, bound to their beds, now stand up like human masts— / Deafness passes through us like a police whistle” in the poem “Alfonso Stands Answerable” (p. 15). In the poem “That Map of Bone and Opened Valves” (p. 16), however, Kaminsky offers an attempt at simile and then denies it: “The body of the boy lies on the asphalt like a paperclip. / The body of the boy lies on the asphalt / Like the body of a boy.” When do you think similes and metaphors can be most effective? Why do you think Kaminsky rejects their use in some cases?

- The townspeople of Vasenka hang puppets from their windows to represent loved ones who have been killed. Alfonso and Sonya Barabinski are puppeteers, and Momma Galya owns the puppet theater in the town's public square. What might these puppets symbolize for the townspeople? Does that symbolism change over the course of the play?

- There are three poems titled “Question” in Deaf Republic (p. 28; 46; 66). What do you make of them and their answers? What other answers might you give? If you were to write a poem in the same structure, what would you ask? How might you answer?

- In an interview with the Massachusetts Review about Deaf Republic, Kaminsky said: “I am not a documentary poet; I am a fabulist. And, yet, the world pushes through, the reality is everywhere in this fable.” What might it mean to think about Deaf Republic as a fable? Have any fables played a role in your life?

- Later on in the same interview, Kaminsky noted: “My job is to make this border between the shelter of fable and the bombardment of reality a lyric moment, I feel.” Can you think of times in your own life when you took “shelter” in a fictional story? What allowed you to do so? What brought you back to reality?

- Across the collection, there are a number of poems whose titles describe a type or a genre of lyric: two poems titled “Lullaby” (p. 27; 64), one titled “Elegy” (p. 38), and another titled “Eulogy” (p. 45). What did you expect when you read each of those titles? Have you encountered these types of lyrics at any other times in your life? If so, did those past experiences affect how you read these poems?

- After his wife’s execution at the hands of occupying soldiers, Alfonso Barabinski agrees to kill a soldier for a box of oranges: “Our boys want a public killing in the sunlit piazza... / The boys have no idea how to kill a man. / Alfonso signs, I will kill him for a box of oranges.” (“Above Tin Roofs, Deafness,” p. 39). How would you describe the relationship between violence and the mundane in this scene? Are there any other moments where this juxtaposition occurs in the book? What might this capture about the tensions of war?

- “Each of us / Is a witness stand: / They take Alfonso / And no one stands up. Our silence stands up for us” are the last lines of the poem, “The Townspeople Watch Them Take Alfonso.” What does it mean to witness? To be a witness? How can we interpret the townspeople’s silence?

- Throughout Deaf Republic, Kaminsky experiments with line breaks and dashes to disrupt conventional grammar or phrases. Are there places in the book where his choices surprised you or changed how you might have otherwise read a particular poem?

- Over the course of the book, Kaminsky explores ways that language can be discarded, chosen, remade, unmade. How has your use of language evolved over time? Can you think of examples in your own life when words or other forms of expression changed in significant ways?

- Across the poems in Deaf Republic, deafness takes many forms: “Deafness passes through us like a police whistle.” (“Alfonso Stands Answerable,” p. 15); “In these avenues, deafness is our only barricade” (“Checkpoints,” p. 22); “A language— / See how deafness nails us into our bodies.” (“Search Patrols,” p. 63). Were there moments in the book that challenged your understanding of deafness? How so? As Kaminsky reminds us in the closing note, “The deaf do not believe in silence. Silence is the invention of the hearing.” What do you think he means?

- Throughout the book, Kaminsky includes illustrations of words and phrases in sign language. What did you make of these drawings? Have you seen drawings like these in other books you’ve read? Did they affect the way you encountered and thought about the poems?

- Though the “I”s of each act in Deaf Republic are adults, the collection offers many reminders of the impact of war on children: from the boys in the piazza to the girls at the puppet theater to the orphaned Anushka. After Vasenka surrenders, “On some nights, townspeople dim the lights and teach their children to / Sign…Don’t be / Afraid, a child signs to a tree, a door” (“And Yet, on Some Nights,” p. 71). How do you understand these lessons? What do children inherit from adults at war? How might this poem relate to other periods of wartime and post-war recovery?

- In an interview with Slate, Kaminsky writes that the poem “We Lived Happily During the War” is meant to serve as a “wake-up call; to prevent people from reading Deaf Republic as a tragedy of elsewhere.” As you consider your own communities, family histories, and lived experiences, as well as news stories from around the world, how do you find yourself responding to that quote?