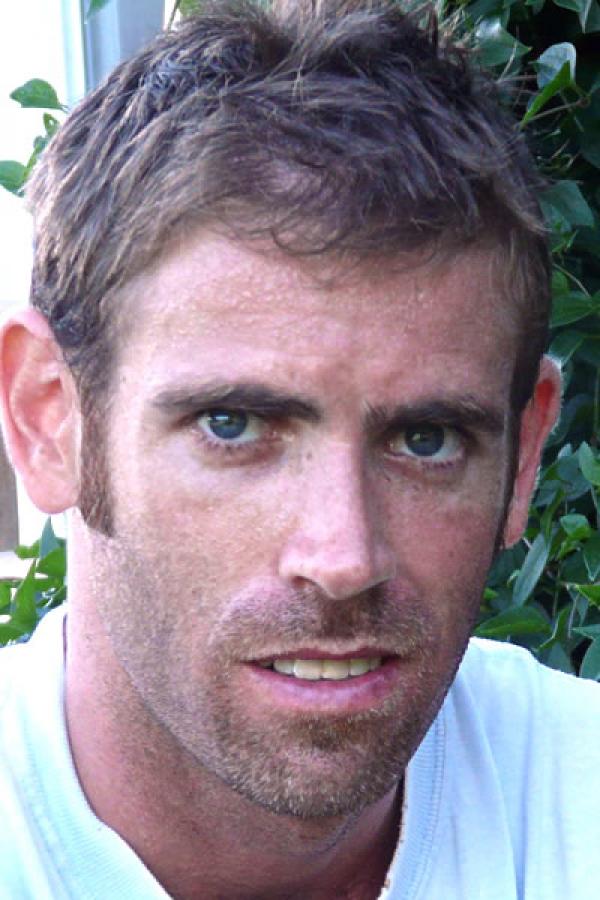

Vinnie Wilhelm

Photo by Zoë Klugman

Bio

Vinnie Wilhelm was born in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1978, and raised largely in Southern California. His fiction has appeared in The Virginia Quarterly Review, Harvard Review, Glimmertrain Stories, and The Southern Review. His current project is Fauntleroy's Ghost, a somewhat historical novel about Hollywood, Leon Trotsky, and the Cuban Revolution, among other things. He lives in Philadelphia.

Author's Statement

I am deeply grateful to the NEA for its faith in and generous support of my work. Spending so much of my time alone in a quiet room, making up stories, for no money and without much encouragement, has often caused me to feel that I might be wasting my life. I'm sure every artist must consider this dark notion once in a while. I believe strongly in the power and importance of art, but this doesn't always translate to a commensurate belief in the power and importance of my art--especially in the face of the power and importance of paying rent, or buying groceries. This fellowship is a tremendous boost to my confidence, and fundamentally alters my practical circumstances. I am humbled by this gift. It will keep me going for a long time.

From the novel Fauntleroy's Ghost

The sky over Westwood was synthetically bright, clouds of noxious smog lit yellow like the center of a fresh bruise. Stucky returned late to his hotel, feeling strangely ecstatic, a lightness in his bones. In the lobby a pretty Latin girl stood near the elevators with a leashed ferret. She smiled at Stucky; the ferret did not. How mystifying and full of possibility the world seemed. True, Raskin was dead, his old pal Raskin, but to feel bad for Raskin was to misunderstand and perhaps dishonor him. This was a man who had smuggled contraband Aztec relics up from Oaxaca in the hold of an old racing sloop and once had sex on an airplane with Feiticeira, the Vanna White of Brazil. To die before his time in a mysterious explosion at a fashionable Brentwood address was a stroke of Raskin's peculiar genius, really. Stucky would die alone in the Lysoled quiet of some flowerless hospitable room, plastic tubing up his urethra and nose. The day nurse comes in whistling a show tune, empties the bedpan before she even realizes--this was how Stucky would die.

But in the meantime: life. Back in his room he felt vital, too wound up for sleep. He drew back the curtain and stood gazing out on the city's long carpet of lights stretching away to the east, toward the mountains and the endless scrub brush desert and the great brutal sweep of America churning away in the dark. Nathalie was so hot. It wasn't even that Stucky wanted to lay her, exactly, but more that beauty of her kind bespoke a fabulous potential swirling gently in the ether. Certainly they had made a connection. In her hour of need, in her moment of desolation and loss, he had bought her strong drink and made her laugh. He was sympathetic but not mawkish--a difficult balance to strike. It was a hazard of his solitary existence that Stucky sometimes forgot how socially adroit he could be. At certain times, in short bursts, he could be very adroit, socially. He could make incisive remarks, he had an interesting mind--interestingly dark. Should call her tomorrow and check in, just to see how she's doing. Though he didn't have her number, she had his. There was noise in the closet. Stucky turned from the window. The closet door opened and Raskin stepped out.

They stood there looking at each other for a few long seconds. Raskin smiled. He spread his hands, palms displayed, and cocked one foot up on its heel in a vaudevillian gesture of ta-da.

"Raskin," Stucky hissed. "I should have known."

- excerpt originally published in Virginia Quarterly Review.