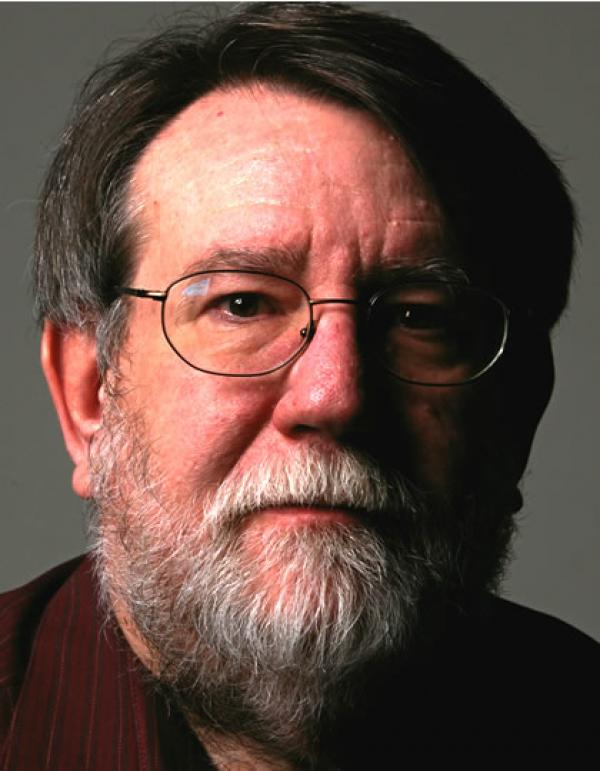

James Reed

Photo by Anna Reed

Bio

James Reed received his MFA from Warren Wilson College and is a former instructor of creative writing at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, where he also served as Fiction and Managing Editors of The Nebraska Review. His short stories have appeared in a variety of literary magazines, including Bat City Review, Brilliant Corners, River Styx, and West Branch as well as the anthology Tribute to Orpheus (Kearney Street Books). He received the Charles B. Wood Award for Distinguished Writing from Carolina Quarterly and an Individual Artist Fellowship Master Award in Literature from the Nebraska Arts Council. His work has been a finalist in competitions for the Spokane Prize for Short Fiction, the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction, and the Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction. He lives in Omaha, Nebraska with his wife and children.

Author's Statement

The immense honor of receiving an NEA Fellowship is a deeply gratifying gesture of encouragement. Aside from the obvious and enormous practical benefits the award confers, the most important boon is the boost in morale. It is so easy, with acceptances often few and far between, to feel a great deal of effort is being expended to no particular effect. What a treat it was, on notification, to hear someone discuss my work in terms of a career. The vote of confidence represented by the Fellowship is an extraordinary gift.

From the short story "A Few Minutes of Your Time"

"I'm sorry to say you're overqualified. Terribly so, really. We wouldn't know what to do with you."

Guy learned early that in offering a suggestion he made himself sound desperate.

There was little else more impolite.

The resulting silence was the express desire that he have the manners to vanish.

"You put someone on the spot that way, the interview's over," said Dori. "Who's going to hire the likes of you?"

He was long past having problems he thought sex could fix.

Still, it couldn't hurt.

Probably.

College kid jobs, college kid wages.

He was tired of making do. He wanted to buy a snowshovel without worrying, without thinking about it first. He wanted to sign a check and not subtract it to the penny before handing it to the clerk.

He wanted Fred Stottelmayer's liquor tab, a month's worth, to be his own disposable income.

He would buy Dori a new coat. It was the one economy she did not mind, owning the one cloth coat for the most bitter cold. It was fifteen years old and worn only a few days a year. Replacing it would be a luxury bordering on lunacy. She would not in her wildest dreams credit the thought.

He wanted a coat roughly the cost of a small car. He knew the right stores. Extravagance this grand was the only possible gift. Anything else, anything smaller, and she'd be annoyed, and rightfully so. Why should he gut their budget for something so foolish? He was trying to fail. He was sabotaging her.

She wished he'd give her cause to say it. He could see it in her eye, and she knew he wouldn't. He was as careful as careful could be.

Do something to let me hate you.

Life could turn so easy.

His mother pondered the question so long that Guy knew she wasn't stalling. She wasn't fabricating an answer she thought either of them would find acceptable. The idea simply hadn't been presented to her.

"Anymore," she said, "I'm not sure it's a matter of missing him, quite."

"Do you think about him?"

"Yes," she said, "but you have to add it up. We were married for thirty years. Twenty-nine, but close enough. He's been dead for twenty, and my first twenty years I didn't know he existed, so it's thirty with and forty not. He's in the middle of it all."

Guy thought of his father's picture on the end table. She picked it up while dusting and returned it to its place, same as the ash tray and the porcelain owl.

She pulled her keys from her purse. "How odd that you should ask," she said. "It puts such a temper on the day."