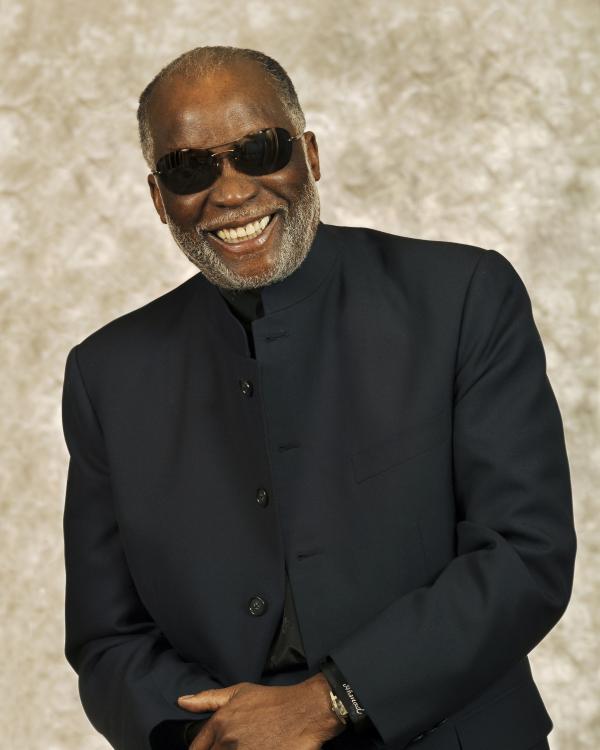

Ahmad Jamal

Photo by Tom Pich/tompich.com

Bio

One of the subtlest virtuosos of jazz piano, Ahmad Jamal's uncanny use of space in his playing and leadership of his small ensembles were hallmarks of his influential career. Among those he has influenced is most notably Miles Davis. Davis made numerous and prominent mentions of Jamal's influence on his playing, particularly in his use of space, allowing the music to "breathe," and his choice of compositions. Several tunes that were in Jamal's playlist, such as the standard "Autumn Leaves" and Jamal's own "New Rhumba," began appearing in the playlist of Davis' 1950s bands. Jamal's textured rhythms on piano influenced Davis' piano players as well, from Wynton Kelly in the 1950s to Herbie Hancock in the 1960s.

Jamal's piano studies began at age three, and by age 11, he was making his professional debut with a sound strongly influenced by Art Tatum and Erroll Garner. Following graduation from Pittsburgh's Westinghouse High School, he joined the George Hudson band in 1947. In 1949, he joined swing violinist Joe Kennedy's group Four Strings as pianist. This led to formation of his trio Three Strings in 1950-52, which debuted at Chicago's Blue Note club, and later became the Ahmad Jamal Trio. His 1958 album At the Pershing became a surprising smash hit, highlighted by his interpretation of "Poinciana." With the popularity of the album and the advocacy of Davis, Jamal's trio was one of the most popular jazz acts in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

For the most part, Jamal worked in piano-bass-drums trios, using the intricate relationship of the band to explore his sound, directing the trio through seemingly abrupt time and tempo shifts. His piano virtuosity was also welcomed by a number of orchestras, and his abilities as a composer are considerable. His approach has been described as being chamber-like jazz, and he has experimented with strings and electric instruments in his compositions.

Among his many awards are the Living Jazz Legend Award from the Kennedy Center and the Officier de L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from France.

Selected Discography

At the Pershing/But Not for Me, Chess, 1958

Free Flight, Impulse!, 1971

Big Byrd: The Essence, Part 2, Verve, 1994-95

After Fajr, Birdology/Dreyfus Jazz, 2004

It's Magic, Dreyfus Jazz, 2007

Interview by Molly Murphy for the NEA

January 11, 2007

Edited by Don Ball

STARTING AT THREE

Q: When did you first begin playing piano?

Ahmad Jamal: I started playing at three years old, which is not a first, but it's very unusual and very rare. Erroll Garner, who was a person from my hometown, also started playing at three. And you have other areas of expertise, like Tiger Woods. His father started him at a very young age. When you start at that young age, I don't think you make the choice. I think the choices are made for you.

Q: How is it that you started at three?

Ahmad Jamal: I just sat down and started playing. And I had a wonderful uncle, [who] passed away, and he was sitting down playing the upright in my mother's house one day and he said, "I bet you can't play this," teasing me, as grownups do to children. And of course, everyone fainted when I sat down and played every note that he was playing. And the rest is history. By the time I got to kindergarten, the teachers were just baffled. They said, "You have to take this boy to a teacher," which my mother did for a buck a lesson. She saved her car fare in 1937 and gave me the lessons at a buck a whop, and that's why I'm just returning from Thailand right now for the 79th anniversary for the king there, because of my mother. I've been all over the world. So that's a success story, because of my mother. One dollar a week in 1937, because she walked home.

Q: When you started playing, you probably don't even remember it.

Ahmad Jamal: Oh, I remember.

Q: You remember being three and playing?

Ahmad Jamal: Oh sure, sure. I have some recall at three, yeah. I also recall a gate that would keep me from falling down the steps at that age, too. Oh yeah, I have some recall, not as vivid as five or six, but I have some recall.

Q: Did you receive instruction on the instrument when you were young?

Ahmad Jamal: I was taught by two masters, one: Mary Cardwell Dawson. Mary Cardwell Dawson, who started the first African-American opera company, and there hasn't ever been one since. She was responsible for many of the Afro Americans being in the Met for the first time. That was my first teacher. When she left for Washington, DC, I had to get James Miller, who was another master. And after that, George Hudson came and made me leave my happy home, because he took me in his big band at 17 and I've been on the road ever since. But I was exposed to all kinds of wonderful music. And I had an aunt, an educator down in North Carolina, who used to send me reams of sheet music, so by the time I was ten years old, I was playing with guys 60 years old, and they couldn't believe it, because I knew all the songs. And I still draw from a large, large body of work because of my aunt. I got this in multiple directions; from my sister, from great teachers, and from relatives who were educators that sent me music. So it was a combination of things.

Q: Do you remember any one or two pivotal experiences when you were young?

Ahmad Jamal: That's an interesting question, because there are some events that certainly were inspiring. Erroll Garner's Savoy recording of "Laura" was pivotal. I heard that in the '40s, gorgeous. It still is gorgeous.

I think Art Tatum's "Flying Home" and my experience meeting Art Tatum when I was 14 years old in a jam session, because he was a phenomenal, extraordinary talent. I was working in a nightclub underage in the very wee hours of the morning, and he came through Pittsburgh and started a session. And he was the last one to play, rightly so, because you didn't play after Tatum. That was pivotal.

And of course, my appearance at Carnegie Hall, my first appearance there with Duke on his 25th anniversary was pivotal. It was Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker with strings, Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz, and myself. I'm the only living headliner. So that was in 1952. That was pivotal.

And there were some things that were revolutionary. There was "Salt Peanuts" and "Groovin' High" by Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. You had to send off for records then, and you waited and waited and waited for the delivery with all kinds of anxiety and enthusiasm to open the package with these wonderful breakables, records that were sent by mail. So those were some of the pivotal things that happened in my life experiences.

PITTSBURGH

Q: When you were taking lessons and learning music, were you gravitating towards any type of music?

Ahmad Jamal: I come from a wonderful place that has few parallels and that's Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. And in Pittsburgh, we don't have that separation of the European bodywork and American body. We study everything. All we do is discard the bad. If the opera's bad, we discard that. If there's some European composer that's bad, we discard that. If some American composer's bad, we discard that.

It's all classical. I coined the phrase some years ago, "American classical music." I'm the one that started that. Duke Ellington didn't call himself a jazz musician. I'm not paranoid about the word, but I'm not a jazz musician -- I'm a musician, and we are multidimensional folk. And if you want to do what we're doing, you have to know the "Etudes" by Franz Liszt. You have to know "Take Five" by Dave Brubeck. You have to know all these things.

So this is a wonderful art form, the only art form that started in the United States besides American Indian art, both of which are pushed way back as far as exportation is concerned. We didn't have that in Pittsburgh. We studied all forms of music. And that's a wonderful place.

Q: Many great musicians came from Pittsburgh.

Ahmad Jamal: Billy Strayhorn, whose family I sold papers to. George Benson comes from there. Stanley Turrentine, Art Blakey, Ray Brown, Mary Lou Williams, Dakota Staton, the great singer, and so many people come from Pittsburgh. It's a really unusual town -- akin to New Orleans, akin to Memphis, akin to Philadelphia. There's some spots, pockets on earth like that, but you can count them maybe on two hands.

All of us come from the same town, but all of us are different, and all of us have a certain approach that's different from other artists in the world. For example, George Benson, he's different. Stanley Turrentine played differently. Erroll Garner played differently. I played differently. Art Blakely, one of a kind, Ray Brown, the same thing. No one played like Ray. Roy Eldridge is also from my home town. Earl Hines is also from Pittsburgh. All these styles indicate there must be something in the water.

THE NEW GENERATION

Q: Do you listen to much music?

Ahmad Jamal: I listen to everything. I turn off that [music] I don't like, though. But I'm also engaged in fostering the careers of some youngsters now. We're co-managing, my manager and I, some incredible talent. We're co-managing Hiromi, who is an outstanding, extraordinary musician. I have a wonderful group headed by a man from Caracas, Venezuela, José Manuel Garcia, International Groove Conspiracy. We have just signed a co-management deal with this incredible Mina Agossi from France. So I'm not only listening; I'm doing a lot of management, something I did back in the late '60s. I had a record company I managed also, but I hadn't ventured into that for about 30 years. But I'm not only listening, I'm fostering some young careers.

These are extraordinary people now I'm talking about, because now you have to be extraordinary or different in order to make it, and these people have both qualities. And it's interesting, because I listen to them and I listen to all these young lions who are out there. Technically, it's amazing what's happening now. But this is what this music has done; this music has produced all these young lions and lionesses. And it's extraordinary, the influence. Well, for example, Berklee School of Music, people come from all over, and that started with just an idea. Now Berklee is welcoming people from all over the globe. This is the strength of this art form.

Q: You said there are so many young lions and lionesses out there. Technically, do you think people are having a hard time finding their own voice today?

Ahmad Jamal: You know what it is now is there's a lot of wonderful, talented musicians, but the emergence of a Art Tatum, or a Dizzy Gillespie, or a Charlie Parker, or a Duke Ellington is very rare, you know. The statements are quite similar that we're making now. The high tech has created a lot of dissemination, but it has created a lot of sameness, in my opinion. That doesn't say there's not going to be some emerging Sarah Vaughans, or Billie Holidays, or Duke Ellingtons, but right now, it's a rarity to find that statement being made, that definitive statement that is so identifiable. I mean like Billy Strayhorn's writing. "Lush Life" is not being written now; "Take the A Train" is not being written now. There's a lot of stuff being written, but statements are another thing, a musical statement that's going to last for centuries, or years and years and years. You know, there are 6,000 kids within a few miles right now still trying to learn Mozart. Duke Ellington's a baby compared to Mozart. And that shows when something is valid, when a statement is made, it lasts a long time. So I don't know if we're making those kinds of statements now, musically.

Q: Do you ever imagine 200 years down the road, are people going to be listening to your definitive recording of "Poinciana"?

Ahmad Jamal: Well they've been listening a long time already. I recorded it in '58.

LIVE AT THE PERSHING

Q: Can you tell me about that recording session?

Ahmad Jamal: That was captured because of my colleagues at that time, my extraordinary drummer, Vernell Fournier, and extraordinary bassist, Israel Crosby, and I had a little something to do with it. And it developed to the extent, I went to Leonard Chess and said, "I have to record this on location. I'm not going to play it anymore, perform it anymore until we record it, because I'm afraid someone's going to take the idea and run with it." So that's how it developed, because I was an artist in residence, which is extremely important. When you're an artist in residence, it means a lot, because you can sit there and develop, and develop, and develop. And we were artists in residence in Chicago at the Pershing Lounge. When I left New York, I went to a man named Miller Brown and I said, "Miller Brown, I don't want to travel anymore. I want to stay in one place." He said, "Sure, I'll pay you $2 a week and you've got a job." He paid me a little more than that. I said, "But you have to get me a Steinway," so we found a Steinway somewhere with a broken soundboard with wood screws in it made in 1890, and it still sounds crystal clear on the record. So we had the Steinway there with the sculptured legs at that time, and I stayed there and recorded one of the most historic instrumental records in the history of our industry.

It was a million seller, which was unheard of. It was on the charts for 108 weeks, not because it was something that was pitched to the public, no, because it was a 7:35 record, which was diametrically opposed to airtime. No one's playing a 7:35 record, forget about it. You were not going to get any airplay. It was too long. We got AM, all the AM/FM airplay we wanted, and not only that, they made an EP from it. And it launched for the first time instrumental 45s. Before it was only Perry Como and Dinah Shore, people like that were getting EPs at that time, extended play records, but this launched the beginning of instrumental EPs.

Q: What is it about the performance?

Ahmad Jamal: It had all the spontaneity and all the excitement that happens when you do a record, but particularly, on location. They called it a live performance. All performances are live, whether they're in the studio, but I call them remote recordings, removed from the studio. The Van Cliburn concerts, what got him over was a location concert, it was removed from the studio, so there are certain things that happen with an audience that don't happen. The studios become very surgical at times. And with the audience, all the mistakes are there. You have to live with them. But the whole setting is one that dictates sometimes the best results.

AUDIENCES

Q: And so when you're performing, do you have a preference between an intimate club setting or a large audience?

Ahmad Jamal: I don't do many nightclubs now. I only do some special clubs. I do Blues Alley [in Washington, DC]. I've been doing that for 25 years. I used to do it every year with Keter Betts but we lost Keter Betts, extraordinary musician. So Blues Alley, I do the Regatta Bar in Boston, because I love Cambridge. I like the atmosphere there. Here [in New York City] I started doing the Blue Note. But right now, we do a lot of stuff in France. We do a lot of venues in France, but they're all theaters.

Q: Why is that?

Ahmad Jamal: Because I think I've graduated to the point that I like that discipline. I like the discipline that goes with working in theaters and venues that are not nightclub settings. But I'm not against nightclubs. There are certain things I enjoy about sitting down, as Ben Webster used to say, "Taking your shoes off for a week." And so I can take my shoes off, according to Ben, for a week when I'm in the nightclub and we can develop certain things, as well.

Q: So it's just a more intimate setting and less pressure. Is that what you mean?

Ahmad Jamal: There's the same approaches involved, whether I do theater, or whether I'm doing Thailand, a big hall there, whether I'm doing Milano, or I'm doing the Blue Note in Milano, because I've done that room before. It doesn't matter if I'm doing one of the great halls in Perugia. It doesn't matter. My approach is basically the same. I am a person who tries to be consistent and this is an acquired skill or something that's acquired over a long period of time. I'm thinking about what I'm going to do on my next engagement, and I'm drawing from a large body of work, as well. I'm drawing from the South. We lived in several eras. I was a kid listening to Jimmy Lunsford, Duke Ellington. And I was a teenager listening to Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. I'm in the so-called electronic age. And I studied both the European body of work, to a certain extent, as well as the American body of work, so I'm drawing from a large body of work, as Gil Evans did when he started writing for Hal McIntyre years ago, and then he graduated up to writing for Miles [Davis]. He was extraordinary. Thad Jones was the same way; he was drawing from all his experiences with the big bands, and Thad's writing used to make your hair stand on end. So these are people that are drawing from a large body of work. So you know, I have the same presentation, whether I'm doing a nightclub or a concert hall, because I have a certain programming technique that I've developed through the years and it works.

THE AHMAD JAMAL SOUND

Q: Can I ask you just a little bit again about your approach or your voice? I think that especially your use of space reveals a confidence. You have to have confidence as a musician. Was that something that you consciously planned, or was it just the way that you communicate?

Ahmad Jamal: Well they call it space. They call it space. I call it discipline. It's part of my discipline. And I acquired this discipline because of working so many configurations. I've played with every configuration known and unknown to man. I've played with just saxophone and piano, when I was growing up, no drums. Big orchestras, big bands, I grew up in big bands. I've played for singers, accompanying singers.

So and then I had to become a leader, so I had to write, because 90 percent of my stuff was written. I used to sit and write for guitar, bass, and piano. My early recordings were written arrangements. Of course, there was a space there for improvisation and soloists. So I think what they're hearing, I call it my discipline that I acquired over the years, a certain amount of holding back. You know it's just like dynamics. I don't think you can play loud all the time. I don't think you can play soft all the time. And I don't think you can play all the time. You have to respect what they call a rest, and you have to respect openness, as well. If it's too congested, when it gets too complicated, something is wrong. I think I acquired that discipline that people call space over the years, because I've worked in so many configurations and I've been a leader a long time. I've had a group for 55 years.

Q: Miles Davis was certainly influenced by your work -- did you two ever talk about it?

Ahmad Jamal: I would rather have an emulation than being completely ignored. Miles is my biggest fan, but that was a mutual admiration society, because Miles was an extraordinary historic musician. You know he used to hang with Charlie Parker and he began very early. He comes from a town also that's famous for musicians, St. Louis. It's a remarkable place for musicians. A lot of guys come from there and ladies that can play. That's another pocket. So Miles's background dictated a lot of his success, just like Pittsburgh dictates a lot of your success in music.

Q: Did he talk with you about your influence on him?

Ahmad Jamal: We had a quality relationship, not quantity. We lived a block-and-a-half from each other for a while, because I lived at 75th and Riverside Drive. He was on 77th Street with his brownstone. But as we needed to hang, we had the mutual respect and I prefer it that way, because Miles was a different kind of guy. And all I knew from Miles was his admiration of what we were doing and his wonderful recording of "New Rumba," and his support of my career at a time when it was very important. But as I said before, I was a big fan of Miles as well.

IMPRESSING ONE'S SELF

Q: Do you aspire for your peers, musicians to perceive you in any specific way?

Ahmad Jamal: No. This is dangerous when you're thinking about how people perceive you. It's good to want to make a good impression, but I want to impress myself first. Then if somebody's impressed further or somebody besides myself, then fine, I'm very happy. I'm still discovering my own potential at 76 years old. I'm still doing things. Of course, you know, you don't ever achieve everything that you have in mind, but you can reach a happy medium, so I'm trying to reach that happy medium. And I'm writing. I'm doing some things I want to do solo-wise in my home. I'm setting up something with my engineer where I can do some solo work, some archival things. But I don't ever think, "I want to impress this guy." You can't be preoccupied with it. To me it's an abnormal aspect of our art form to have to have applause. I mean it's wonderful, but when you don't get applause, it's something that can hurt. And it might be that what you're doing is very valid.

Q: Do you ever find yourself in that position?

Ahmad Jamal: I have been around mild applause. I've been around standing ovations. So I know a little bit about both. It's something when you have to live for applause, you know? That's a little abnormal, but that's one of the things in our business, so one has to be careful about being concerned with impressing others. You have to impress yourself. If you're pleased with what you're doing, if you're happy on a bandstand, people can feel that. There's an exchange between you and your audience, always, without fail, because people say, "Hey, they're having a ball. Let's have a ball with them!"