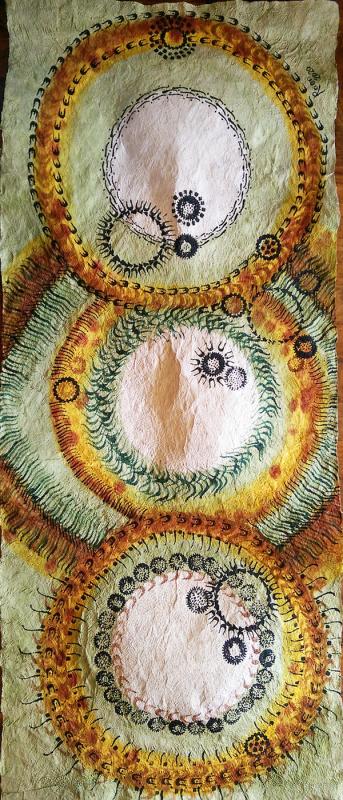

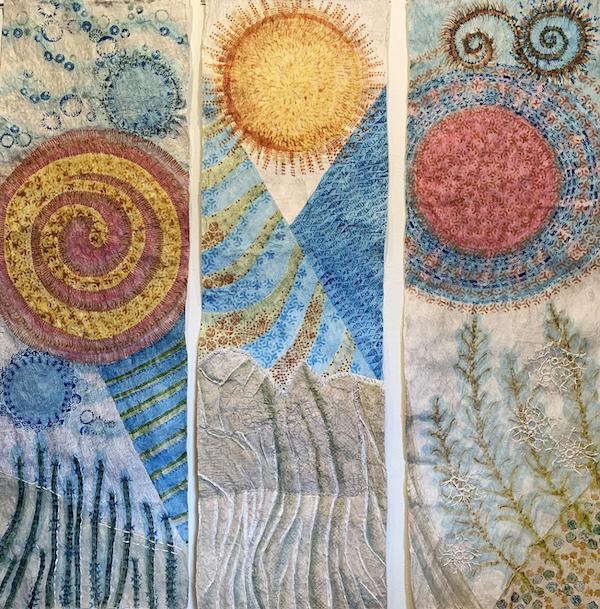

Roen Kahalewai Hufford (Hawaiian)

Photo by Lynn Martin Graton

Bio

Of Native Hawaiian descent, Roen Halley Kahalewai McDonald Hufford carries on the art of ka hana kapa (making barkcloth) and is a leading figure in the reclaiming of this nearly lost art. Barkcloth is made in many parts of the world, but in Hawai’i, has reached levels of remarkable refinement and was once as essential to life as food.

With no loom-woven fabric, barkcloth once swaddled newborns, served as clothing, was made into blankets, adorned sacred images, and was used to prepare burials. So important was wauke (Broussonetia papyrifera), the plant that provides the strong bast fiber, it was carried to the Hawaiian Islands on canoes by the first Polynesian settlers. Kapawas made throughout the year and it is said you could hear the beating of kapa before you saw a village. With the introduction of cotton in the 19th century, kapa fell out of fashion, and the skills nearly vanished.

Hufford was born on the island of Molokaʻi and grew up on the windward side of O`ahu. From an early age, she was immersed in Hawaiian values—respect for the land and the importance of kokua (helping) family and community. After graduating from the University of Hawai`i Mānoa, Hufford spent many years as a florist. In 1990, she and her husband Ken moved from Kauaʻi to Hawaiʻi Island to grow organic vegetables on her mother’s farm in Waimea.

The 1960s to 1980s was a time of intense interest in recapturing traditional Hawaiian music, dance, crafts, and values. Hufford and her mother Marie Leilehua McDonald (a 1990 NEA National Heritage Fellow) became important participants in the movement. Hufford helped her mother research and document traditional lei and publish Marie’s two seminal books on leimaking. From there, they focused on retrieving the skills of ka hana kapa. They planted patches of waukeand dye plants, studied museum collections, and collaborated with woodworkers to make the needed tools. With her mother’s passing in 2019, Hufford inherited the legacy.

Making kapa is a labor intensive process. After peeling and cleaning the bast from 7- to 10-foot stems, the fiber is soaked in sea water, beaten with wooden mallets into thin sheets, and then felted into larger pieces. In Hawaiʻi, delicate watermarks are imprinted by patterned beaters and the dried kapa is decorated with natural colors derived from flowers, fruits, bark, and soil. Dyes are applied with handmade stamps, brushes, bits of wood, and even leaf stems.

Over the last 30 years, interest has grown in ka hana kapa and Hufford is a leader in the effort, widely appreciated for her artistry, skill and generosity. She hosts a weekly kapa hui (kapagroup) at her farm where students of all ages, backgrounds, and skill levels come to learn and share with each other. She is one of the few kapamakers in Hawaiʻi with enough wauketo share, and provides wauke “starts” for others. For Hufford, farming and making kapa are inseparable. “If you are going to beat kapa,” she says, “you have to know how to cultivate the plant.... Were it not for the resources the land gives us, we couldnʻt do this.”

Hufford’s work is collected and exhibited widely in Hawaiʻi and internationally. Like her ancestors, she finds inspiration for her designs in the richness of her environment. With her students, Hufford demonstrates locally and beyond. She collaborates with other Polynesian barkcloth makers, helping to bring renewed recognition and relevance to the tradition of ka hana kapaacross the Pacific.

—By Lynn Martin Graton, folklorist, arts consultant and fiber artist, Waimea, HI

Kapa 2. Photo by Lynn Martin Graton

Kapa 5. Photo by Lynn Martin Graton