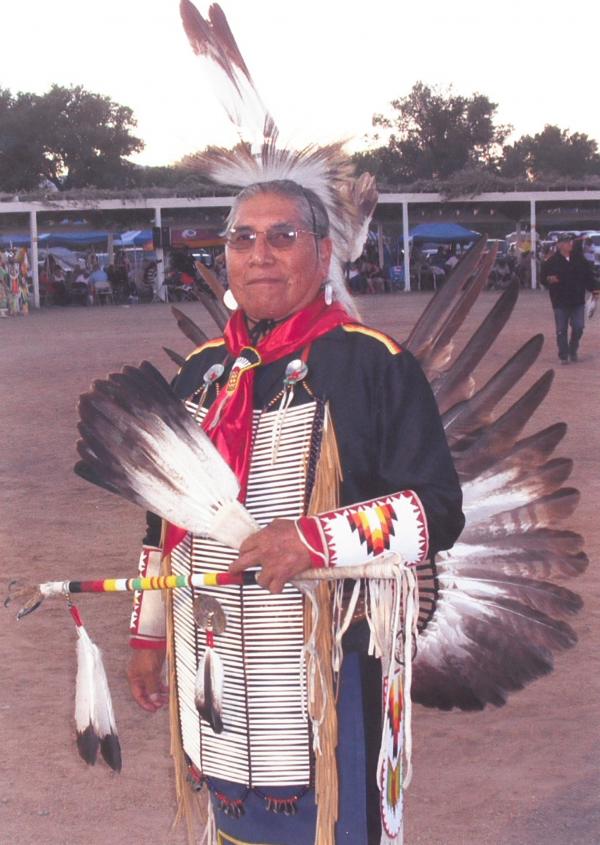

Ralph Burns

Photo courtesy of Ralph Burns

Bio

Pyramid Lake Paiute elder Ralph Burns is a revered storyteller and native-language specialist. Burns grew up on the Pyramid Lake Paiute reservation in Nixon, Nevada, where he learned the Numu (Northern Paiute) language and traditional stories from his family and community members. After serving in the 1st Cavalry Division during the Vietnam War and subsequent years of working in California, Burns returned home to the reservation to devote his life to spearheading native-language revival and revitalization among the Northern Paiute.

At the Pyramid Lake Paiute Museum and Cultural Center, Burns is the cultural resource specialist, serves as a resource for the Paiute language program, and is a frequent storyteller. Burns is also an accomplished traditional dancer who frequently leads the sacred circle powwow dances and has instructed groups at the Pyramid Lake Reservation and Reno-Sparks Indian Colony. For more than two decades, he has taught the Numu language to tribal students, local high school students, and community members, and developed a language curriculum to teach both Native American and non-Native American people. "Without the efforts of Mr. Burns, these traditional arts of the Paiute people and other Indian people would be lost," wrote Sherry Rupert of the State of Nevada Indian Commission in a letter in support of Burns's nomination.

Throughout the region, Burns presents the history, culture, and traditional stories of the northern Paiutes to his community, other tribal communities, and non-Native American audiences. Burns uses storytelling as an integral tool when teaching the language, since traditionally the Paiute language was passed on orally. Catherine S. Fowler, professor of anthropology, emerita at the University of Nevada, Reno noted, "[Burns] never neglects with these audiences to stress the significance of the stories in the Native language as a further show of respect for the language as well as a way to illustrate for non-Native people the beauty and fullness of the language."

Frequently sought-out, Burns has performed blessings and offered Paiute tribal stories at both state and federal ceremonies, including the 2011 Nevada State Governor's Inauguration and the dedication of the Sarah Winnemucca statue at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC. His stories of animals, land, and people are part of the exhibits in the Nevada State Museum in Carson City. In 2011, Burns received the Nevada Heritage Award for his contributions to the many people and cultures of the state.

["Stone Mother" video used courtesy of the Nevada State Museum and producer, JoAnne Peden.]

Interview with Ralph Burns by Josephine Reed for the NEA

September 25, 2013

Edited by Liz Auclair

NEA: You grew up in your grandmother’s house and you grew up speaking Paiute as well as English. Can you talk about your grandmother and her influence on you?

Ralph Burns: Well, my gram, she was born I would say probably about 1884, and at that time they had what they call "boarding schools." And they had people—I guess you would call them Indian police—that went around and literally kidnapped any kids and then sent them off to boarding school [where] they were forbidden to speak the language or use Indian culture. So my gram knew no English and she was young and probably had culture shock. What she did was, her and some other kids ran away from the boarding school –it’s probably a little over 100 miles—and came back. Her parents hid her because they were punished severely [at the school]. So when she became my grandma she still had the language and she had very few English words. When my mom remarried she moved to another state, my mom did, and we were left there with my grandma. So everywhere grandma went we had to go. So we grew up with the language, and that was my first language until probably when I was about six, when I went into first grade. The English-speaking kids that I hung around with, that’s how I started learning English. But I still retained the language.

NEA: Now you were drafted or did you enlist in the Vietnam War?

Burns: I was drafted. In junior year and senior year you choose a vocational trade. And I took some tests and had a choice of being a draftsman, a carpenter, or a painter, and I chose painting. So the last two years in high school part of it was academics and then rest was vocational training. When I finished high school I put in an application to continue. I was accepted in Berkeley, California. I was there about three and a half years, but I advanced quickly because of my previous training. I got into a union and started working and I took a civil service test and I was chosen to paint the Golden Gate Bridge. But at that time they were still using lead paint, so that would’ve affected me. And also it’s pretty dangerous because it’s a lot of wind. So maybe I’m glad that I didn’t go that route, but I was drafted and I got sent overseas. I did my basic training and my advanced infantry training in the state of Washington in the snow and got sent to Vietnam.

I fit right into Vietnam. I see some young kids that were 5’ 10” and taller. In my area where we were sent, they couldn’t survive—they couldn’t make it through the jungle because they were too tall. People who came from the cities, they couldn’t make it. A lot of kids they couldn’t take it out there. They refused to take their malaria pills and their heat pills and a lot of people shot themselves in the foot and stabbed themselves just to get out of the field. But I fit right in. It had no effect on me. Our so-called enemy, they were probably my size, and I kind of look like them; they would come up to me and speak with their language. We had prisoners of war, and I really think about why I’m here now, because I had respect for the enemy. Respect your enemy and just keep going over what you learned on how to stay alive, stuff like that. I think I was blessed by just knowing that being respectful to the enemy because a lot of stuff, bad things happen to the enemy. What I mean by that is I see our soldiers cutting off fingers for rings and knocking out teeth for the gold that’s in their teeth, cutting off ears for trophies. Those things I see and I think what we simply call "karma" now is how our people survived here for many, many thousand years. It is the same thing I believed over there, and I think that’s why I was brought back.

I felt good about coming back, but when I landed in San Francisco I see a lot of people lined up and I thought that was our welcoming committee. At the time I didn’t realize what they were there for; I just thought they were there to welcome us home. But this name-calling started and they were throwing things at us, and I just felt really, really low. And I had nothing to do with the service until about two, three years ago. And I’m glad I came back and I think time healed.

NEA: And when you came back that’s really when you began really wanting to reclaim your language, reclaim those traditions. Is that true?

Burns: Not really at first. I was kind of mad at the world in a way. I started drinking heavily. I was sent to a rehab center in California, and I stayed in that rehab for six months. But I did pretty good there, and I started working for the facility and I worked there for 11 years. And when I was working there we went to the native traditional pow-wows and dancing, stuff like that. At that time I still had nothing to do with the veterans, but I was literally dragged into the circle and was presented with a blanket and was honored for being a veteran, and that kind of started turning my way of thinking.

Where I worked I met my wife and we always go visit her homeland, which is Minnesota, and we usually visit in June, a good time of the year. So I made a comment, “I wouldn’t mind living here.” So that’s what we did. We moved from San Jose area into Minnesota. I only lasted eight months. I never realized how the weather was there—22 below and with the wind chill would get like -40. I lasted eight months in Minnesota and we actually went back to the Bay area because my brother was still living there. We were going to just stay with him and start all over. But we came and visited my mom in Nevada, and we were there about a week and my wife was approached for an interview. She was actually hired and she accepted the job, so it left me there with no job. But I did some volunteer work where I work at now [Pyramid Lake Museum], and they must like me there and so they hired me. Actually, I was the first one hired there and I’m still there 15 years now. People from all parts of the world would come in to ask me questions pertaining to the tribe language.

Back in 1996, they had a survey on the reservation. That’s before I came. And I was told that they surveyed 1,700 people, and of those 1,700 people there was only 71 people that still retained the language, and they were pretty much all over the age of 65. So the people that did the survey told the people there that within 15 years the language was going to disappear if nothing was done about it. In 1997, they created a language program, the year I came. So those two went together. I had the memory. I would say it took me a good two years to have everything slowly come back. A lot of our old people weren't trained or didn’t know how to teach. I wasn’t trained to be a teacher, either, but I guess I could wing it.

And that’s where I’m at today. All the other instructors or the teachers that teach the language today, they all had to have a certification. And I just tell them, “Well, who’s going to certify me?” There’s nobody really that speak the language and know what I’m saying. They got me grandfathered in as a certified teacher. But I think the language really, really took off because they came into the community, went to other communities, and then went into our daycare, our Head Start, elementary school, and high schools. What they did here about seven years ago, they added five new languages to the school system because Spanish and French was pretty much always there in the high school. They added three types of Asian language, the German language, and the Paiute language.

NEA: Now you use storytelling a lot in teaching the language.

Burns: Yeah, there are different kinds of stories. Some stories we only can do during the winter months, or what they say, "after the first frost." I do a lot of mostly short stories that they can grasp because part of the curriculum for the high school is that they have to know one story and they have to do it orally in order to get a grade in their class. So I do short stories for them. They learned single words, animal names, body parts, colors, nouns, verbs, those kinds of [things]. And they start learning to put it together as they advance in their class. But at the end of the school year one of the tests is oral language, and they have to know a song. I was probably one of the first ones that started with the new curriculum, but I was detected with throat cancer and so they had to take out my thyroid. I’m in remission now, but at that time, with the radiation, everything was burnt inside and I couldn’t drink water and I couldn’t really speak.

At that time one of these persons that nominated me was a professor there at the University of Nevada and I worked in her class doing presentations. She allowed some students to get their foreign language [credit] using the Paiute language. Some of the kids now, there’s two that are now teaching the language, and they’re under 30 years old. And I kind of feel proud about that because one’s been with me seven years now, and she had no knowledge of the language, but I went to her literature class and I did a story in the language, and she just liked it so much she came up to me and I told her about the community class. She went and got all her families involved, and she talked to her professor and that’s how she got her foreign language [credit] using the Paiute language.

NEA: That’s wonderful. It’s also great because starting in Head Start it encourages a greater cross-generational conversation. Because of most of the people who know Paiute are over 60 it’s imperative that younger people talk to them.

Burns: Right now I can count three people that started back in 1996 or ’97 that are still living, and that’s just like closing down a library. You know, they’re gone now. We can't get them back. But through the years I think you almost have to know the whole history, how we almost lost it, 1860 wars, two wars, a lot of people scattered, and then when the reservation was created a lot of people didn’t come back. We were actually prisoners of war up there in the state of Washington until 1886. When they released us they didn’t bring our people back to our area or our reservation at that time. We were put on different reservations along with different tribes, and our culture got ripped and also—you might’ve heard about the ghost dance era?

NEA: Yes, I wanted to ask you about the ghost dance.

Burns: In Northern Paiute, there are 23 different bands. We have 13 different dialects in our language. Where this ghost dance started, they use the southern dialect. I learned from my grandma about how it started: that it was a guy, a fellow. They refer to him as “Wovoka.” Wovoka means a cutter, and they say it comes from either cutting wood or the alfalfa. He was invited by his boss to suppertime and they would pray before they eat. He really liked that. He had limited English, but he couldn’t convey the Christian way to his fellow people, so he started using trickery. At the table he probably heard about the eclipse of the sun so he went and told his people that he could make the sun disappear for a while. That happened. People started believing him. He went further than that. He had his boss’s kids take some blocks of ice—in that time they had big blocks of ice—up river in dead of summer, and he said he could make the ice appear. That happened. More people believed him. He wanted to do more things. He even had somebody shoot at him with a shotgun. BBs didn’t penetrate his shirt, and that’s where the war shirt come from up north. My grandma actually see him do things with the fire, and he would have something made up where lead would drop into his hand when he was doing something. Tricky hands, I guess.

NEA: And this is in the late 1800s.

Burns: A lot of people, even up there in the Dakotas, heard about him. And he kind of went into a trance [where] he dreamt about a good place where we’re going to go. That part is true, but I think maybe people add in that [he said] the buffalo's going to come back. And that’s how the tribes in the northern area came down. In those times I think the native people can ride the trains free, so they came down into our area and he gave them the red paint, what we call orchid ochre now, and magpie feathers, and that was supposed to be powerful when they took it. We don’t have war dance. We just have social dances, what we call round dance. It’s just a social dance. It’s used for everything. But they took that power, supposed to be power, up north and they turned it into what we call the ghost dance. We didn’t start it. They did. And, you know, all the bad things happened. But since we’re only less than 150 miles away from the area where it started from, the government, the military, came down hard on us. So from middle of 1890 until 1934 we couldn’t practice our ceremonies, our dances, our songs. That’s where we pretty much lost everything because we were closest to the area where it started. Our reservation when it was created was more like a prison camp, but now it is a good place to be. It’s a remote area, but it’s still serene, our area, the lake.

NEA: You're known as a storyteller as well. Are the stories you tell from your grandmother?

Burns: Growing up with my grandma we were poor. We didn’t have any radios, TVs, anything like that, so our entertainment was storytelling. Some of these stories are actually long. You know, like the coyote’s travels. He does crazy things. They tell me that kids’ attention span is about three to four minutes and adults' is like seven to nine minutes. Also, in a classroom setting I can't do those long stories. So what I’d done was I summarized it. Going against tradition I summarized my stories. And I talked to elders of the things that I do, but I think I’m respected now because I used to ask an elder, “Why is this? What's the meaning of this?” I’d get answer like this: “You’re supposed to know because you’re the teacher.” But now it’s the other way around. Even elders ask me, the people a lot older than me, the people I think that should know. So now I realized I’m the elder now. But I think I learned a lot in the stories, but that’s how I started learning.

NEA: Can you give us an example of a story?

Burns: This is one. It’s about the coyote and the mouse. It’s a short story. They say a coyote was out there hunting one day and he caught a mouse. When he was about to eat the mouse the mouse hollered out to the coyote and told him, “I’m small. If you eat me now you will still be hungry. But if you plant me in the ground later on I will grow up to be big and you will have a lot more to eat.” So the coyote planted the mouse and left. Later on the mouse snuck out. And just the moral on that one is be satisfied with what you have or you will lose everything. And that’s the way I tend to live. I am satisfied, but if something comes to me I’ll accept it.

NEA: How did you find out you got the NEA National Heritage Fellowship?

Burns: Well, I had two professors from the University of Nevada. One nominated me for the Nevada Heritage Award, which I received back in 2011. She came forward and she says, “I’m going to nominate you for the National Heritage Award.” I had no idea what that was at that time. I said, “Sure,” you know, because I didn’t think it was getting [it]. And she went to the [other] professor that I talked about before, a lady that I’d done a lot of work with, she does recordings. I like to share her doing that because if something is recorded for our newer generations it’s going to still be there, so I have a lot of recording done on me with the words and stories and everything. So it’s preserved for our future generation because my grandma did the same thing so I have some of her stuff and people before her. And I gave the songs to my nephew. I worked with a young linguistic person that worked in Berkeley. We have a lot of our stuff stored in Berkeley, so she took some and gave them to me, says, “Use these.” All from way back in 1873, songs, stories. So I gave it to my nephew so now he sings them. So now he’s kind of being called to these old songs. And so I think I’m slowly bringing things back that was once there.

NEA: It’s a long road.

Burns: It is long road. And just talking to the young people, some of them I think will catch on. Even kids maybe like in their 30s, 40s, because to me I’ve noticed whenever a native female reaches the 40-year mark they’re becoming mothers, maybe some of them maybe even grandmothers. They have more responsibility. Maybe kids come to them. “Mom, how you say this?”

NEA: Right. They want to pass that on to their children.

Burns: That’s right. So I’m getting a lot of them, too.