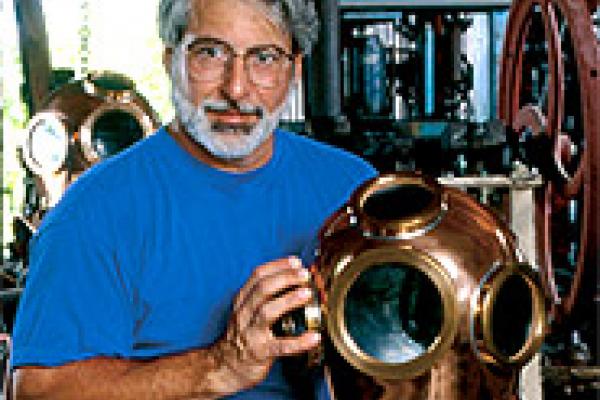

Nicholas Toth

Photo courtesy of the artist

Bio

Florida is the only state in the union where natural sponges are harvested. Tarpon Springs became a center for this commercial activity, attracting sponge divers from the Dodecanese Islands of Kalymnos, Halki, and Symi in Greece. Antonios Lerios, whose father emigrated to Tarpon Springs from Kalymnos in 1905, became a primary equipment supplier for the sponge boats. He created a one-piece diving helmet of spun copper, with redesigned windows, air valve, and breastplate.

Nicholas Toth, Lerios's grandson, decided after he finished college that he should learn helmet making from his grandfather and carry on the family tradition. When Antonios Lerios died at the age of 100 in 1992, Nicholas Toth was the sole inheritor of this specialized tradition. Toth has continued to make innovations on his grandfather's designs. While he continues to receive orders from working divers around the world, his helmets are also appreciated for their remarkable beauty and are sought by collectors and museums. Toth's work was included in the touring exhibition Florida Folklife: Traditional Arts in Contemporary Florida, and his workshop was featured on National Geographic Explorer.

Interview with Mary Eckstein

NEA: Congratulations on receiving the award. Could you tell me about how you felt when you got word.

MR. TOTH: I was basically speechless. I got the call from Barry Bergey around 8:00, 8:30 in the evening so I knew something was up. I really had forgotten all about the National Heritage Fellowship because I had provided the documentation back in '98 when I was first nominated.

My mother hadn't forgotten. In 2000 when I got an individual artist fellowship from our state arts agency, she kept saying, "Well, what about the national award? Why don't you call someone and see what's going on and see if there's something more you need to do?" And I always put it off. Finally, I just forgot about it. So when I got the call I was in shock. I was speechless.

NEA: Which divers prefer your helmets over other helmets?

MR. TOTH: I think a little background would be helpful here. While the use of any kind of diving apparatus for sponge diving began probably 175 or more years ago in Greece, the basic design of the helmet hasn't really changed since. Refinements have been made but there wasn't any other diving equipment for a long time - even here in Tarpon Springs after the first wave of immigrants came in 1905, when they discovered sponge off the coast of Tarpon Springs.

The "hard hat" or the heavy gear was the only type of equipment. "Hard hat" is a slang term for this kind of equipment in the world of commercial diving. If you wanted to dive, you didn't really have a choice - the copper and brass helmets were really the only equipment that existed. Every boat utilized that type of equipment.

It's called heavy gear for a good reason. Compared to other commercial gear it's quite heavy. There's the heavy vulcanized canvas suit that makes the outfit completely waterproof. Then, to keep you down on the bottom, you wear lead weights on your chest and back and shoes made out of steel that fit like slippers. It's all very heavy, probably 150 or more pounds on the diver. Once he gets in the water he's constantly being fed air, which keeps him buoyant.

Now there's lighter gear that doesn't look like the old-fashioned diving helmets. It's basically a triangle-shaped mask that covers your whole face. It looks like a scuba mask, only larger. It's a complete face mask. A lot of the divers now use that instead of the heavy gear.

This new mask was developed because of the economics of sponging. You have more small boats going out now and fewer larg boats. There is one family that still owns three of the traditional 45 foot long sponge boats, which are equipped for this kind of diving, and they do utilize my gear. But most of the boats you see at the sponge docks now are much smaller. Some guys even go out by themselves, others with just one other person as the crew. They're doing it on more of a shoestring budget so they're not using the gear I make, which cost a lot more that the new equipment. The cost of course is a major issue.

There's the issue of experience as well. The divers and the entire crew has to be involved if my gear is being used. There just aren't that many in the business now who have that experience.

NEA: I understand your grandfather made refinements to the original design. Could you tell me about that?

MR. TOTH: He made some modifications. The diving helmets brought over by the Greek island divers and helmet makers in the early 1900s were a more primitive looking helmet. They combined the techniques of the machine shop and the blacksmith shop. They were rather primitive looking compared to what we did here in Tarpon Springs.

My grandfather was a master machinist and engineer with more refined skills and different ideas about how the helmets could be put together. His design was less rough, better looking, and had mechanically superior functionality. And it was an aesthetically superior helmet than what was produced over in the islands.

NEA: Did he make structural modifications?

MR. TOTH: One major thing that he did was tapering the front of the breast plate. The breast plate is the lower part of the diving helmet that fits over the diver's shoulders and around his back and chest. He narrowed it a little, making it less cumbersome. This made it easier for the diver to use his arms to collect sponge more efficiently.

He also moved the faceplate. There are four port holes on it. The middle porthole is the largest one, the main viewing port. The old helmets had them just straight up and down and soldered in very close to the copper sphere. He tilted the top out a little bit so the front porthole, instead of being straight up and down, was tilted down somewhat. He did this to make it easier for the divers to look down at their feet to see the sponge.

He also moved the air exhaust valve which is on the side of the helmet. This is what the diver keeps tapping with his head to let air out of the helmet. This is very important because air is constantly flowing into the helmet and suit - if you don't tap your head every couple of seconds you will become too buoyant and float to the top. To stay down on the bottom you've got to constantly tap this exhaust valve.

He realized that the old-fashioned helmets tended to have the exhaust valve positioned so that the diver had to tilt his head slightly back to tap the exhaust valve with his head. This was taking the diver's focus off the bottom where he's working. So he moved the valve a little bit forward so that you only have to tap your head sideways. This way you don't have to lose focus on the bottom where you're gathering the sponge.

NEA: Have you made any other modifications on those elements?

MR. TOTH: No, I use the same patterns. I use the same everything as my grandfather. I use the same wood patterns. I use the same cast iron mandrel to pound out the breast plate. I use all the same equipment in our shop.

My grandfather's helmets are considered fantastically beautiful. I'll spend a good amount of time to add an aesthetic element to the helmets. The changes I've made -- say like on the port holes themselves, the four lights, you know, on the top part there - I've made them a little bit heavier in the sense of the proportions are slightly thicker compared to what my grandfather did.

But unless I pointed it out to you, you wouldn't be able to tell the difference. I just brought them out a little bit further from the helmet and left the dimensions slightly thicker. I did this just to give an aesthetic balance.

I also spend a lot of time polishing. I use different grades of emery cloth and sand paper to bring out a high gloss to the brass components. I try to create a mirror-like finish on most of the surfaces. It's more of an artistic statement and has little to do with functionality.

I do this to transform the helmet from being just a piece of functional equipment into a piece of artwork that will evoke an emotion and a reaction from the viewer. I want someone to look at it and see it as an object of beauty, and then perhaps at a deeper level consider what it represents. Who wore this helmet? What's the story behind the people who wore this and did this work? And, of course, on another level it has become a symbol of the community and a symbol of our heritage.

NEA: You had watched your grandfather make the helmets and made the decision after college to turn your attention to making them yourself. Tell me a little about this.

MR. TOTH: My grandfather did many other things - he wasn't just a helmet maker. He was a very accomplished engineer and master machinist. He had been doing everything necessary, from an engineering standpoint, to keep the industry going. He made everything from the old-fashioned hand crank air compressors to the parts for the dive ladders to the parts for the propellers. He made the propeller guards. He installed the diesel engines. He would fabricate the propeller shafts, the things called stern bearings and stuffing boxes. You name it, he could do it.

When I was finishing up college, I would come home and help him out on weekends or during the week if I had the time. He decided he wanted to start making more diving helmets when he was 79, 80 years old. He'd had enough of climbing in and out of boats and just wanted to do something else, something that he could pass along to me, I guess. Hell, he had already given me everything but he wanted to do something.

So the idea was that he was going to start making diving helmets and get away from doing the other stuff and I was going to learn. So we started making them.

At first I just sat there and watched. I was familiar with doing different things in the shop but I really didn't know how to make a diving helmet. So I'd watch what he did and slowly over a couple of years I had mastered each step to where I could make a complete helmet on my own. And then when he passed away, I obviously had to do everything, period.

NEA: What was the hardest part of learning for you?

MR. TOTH: It's all difficult at a certain level. None of it is easy.

NEA: DO you have apprentices or anyone learning the tradition from you?

MR. TOTH: I haven't had any apprentices or anything. My 23 year-old son is an actor in Los Angeles. I've never worked with anyone other than my grandfather.

NEA: Is anyone else making this kind of helmet?

Toth: I'm one of the few in the world. I'm very proud of what I do, you know, proud of what it represents. But I'm also sad at one level that there's not more appreciation in our society for this level of craft. It's a world where we've perhaps forgotten the importance of the craftsman, of craftsmanship, of artisans who have the skills to create things that evoke thought and emotion in us. Our focus has gone elsewhere as a society where we don't perhaps appreciate it overall. Of course there are people that do appreciate it but overall, I think we've lost a link in the chain that in a sense helps make our world a little better place.