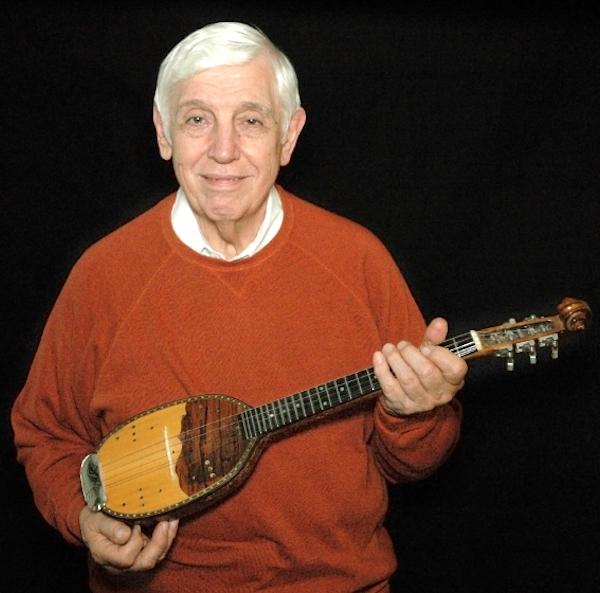

Milan Opacich

Photo by Alan Govenar

Bio

Milan Opacich, born to a Croatian mother and a Serbian father from former Yugoslavia, grew up in the Calumet region of Indiana, home to South Slavic workers in the steel industry. Opacich became interested in string music at the age of four and by the time he was fourteen was playing country music with other members of mill working families. At eighteen he took up the tamburitza music of his familial heritage, an ensemble form of playing string instruments ranging in pitch from soprano (prima) and alto (brac) to cello and bass (berda). After he realized that few people could make this complex variety of instruments, Opacich applied his skills as a tool and die maker to the construction of quality tamburitza. In 1958, after the steel industry began to decline, he joined the Gary Fire Department and set up a small workshop in the basement of the firehouse in order to carry on his instrument making during down times. Today he is recognized as this nation's premiere tamburitza maker. Incorporating ornamental mother of pearl inlay and intricate carving, his instruments are sought after for their visual and musical quality. His instruments have been exhibited at both the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution and at the Roy Acuff Museum. In 2002 he was named to the Tamburitza Association of America Hall of Fame.

Interview with Mary Eckstein

NEA: Congratulations on receiving the Heritage award. Could you could tell me about your reaction when you heard the news.

MR. OPACICH: I was in my shop where I am now when the phone rang. A gentleman congratulated me. At first I didn't know what the congratulations were for -- I thought it might be a salesman congratulating for being the recipient of an insurance policy or something. Then he started talking about the Heritage thing and asked me if I was aware of it. "Yeah," I said, "I'm very familiar with it." He congratulated me again and said, "Well, you are one of the ten recipients of the award this year." I'll tell you it was a strange thing. Right away I thought of my mom and my dad and my late brother and thought to myelf, "Gee, if they were here, how happy they would be." I knew my wife and my daughter would be proud. We talked some more and after we hung up I went into the house. I'm kind of an emotional person, so I had tears in my eyes. But I also had a big smile on my face so my wife knew that it couldn't be too serious. After I told her, well, then we had more tears.

NEA: That's wonderful. Would you tell me a little bit about your experience learning to make tamburitzas and perform the songs?

MR. OPACICH: My parents exposed me to musical instruments very early and I destroyed a few of them in the process. At eight they had me take Hawaiian guitar lessons and, I’m sorry to say, I didn't take to them but I inherited the guitar because you got the guitar with the lessons. When I was 14, we had a neighbor move in who was a country western addict - he played guitar for hours at a time on his front porch. One day I got the nerve to go over. I told him I had a guitar and he asked me to bring it over. He tuned it up and asked if I would like to learn how to play and I said I would. That's how I got hooked on country western music, really, really hooked on it. I wanted to go that route.

I go into a group called the Opossum Hollow Ramblers. There were four of us -- two guitars, an electric mandolin and a washtub bass. We played a few jobs around the area. Then the war ended and a number of veterans from the church I belonged to came back and needed someone to play rhythm in their group. The instrument they wanted me to play was totally unfamiliar --though it played rhythm like a guitar, it was tuned differently. It was easier to chord because there were only three predominant notes to deal with. So I learned that, but at the same time had my eye on the fellow playing the lead instrument, the lead tamburitza, which was made out of a turtle shell. Boy, that really blew my mind. So I formed my own trio and bought a tamburitza by mail order through one of the ethnic papers. It wasn't a turtle shell but it was basically the same instrument. I played in a number of groups over the years. It was a real blessing for me because I love the music.

|

|

NEA: How did you get into the instrument making?

MR. OPACICH: That was always in the back of my mind because as a youngster I destroyed two or three ukuleles. Since it was during the depression my father couldn't afford to buy me another one, so he found a piece of plywood and fashioned out something with a hacksaw that resembled a ukulele and put rubber bands on it for strings. I think that was an inspirational thing – it stayed in the back of my mind. After I left high school, I didn't feel I was college material so I went to work in the same plant that my late brother worked in. He got me a journeyman's apprenticeship for tool and dye. That's where I learned to work with my hands and learned some skills.

While working in the plant I told him about my wanting to make an instrument out of a turtle shell. He was an expert marksman from World War II so we ventured into Michigan City, Indiana, where a friend had a farm with a huge swamp where he swore there were turtles. We sat on the banks of this swamp and lo and behold a turtle raised his head and my brother ringed him. He ran into the water to retrieve him and he hollered for me. Now, I had those waist high rubber boots, you know, and boy, it was a creepy looking swamp. I thought, hey, if there are turtles in there, there's probably also poisonous snakes. But I went in and the water started pouring into the boots the farther in I got, but he located the turtle with his foot, dove down and pulled it out.

We brought it back to Gary, Indiana where we lived. My brother, being a hunter, believed that whatever you shot or killed was for eating purposes. But my wife didn't want to cook it. My sister-in-law didn't want to cook it. So my mom, my dear mom, to keep peace in the family, stewed it for us in a big pot. After two hours I looked into that pot and there were these legs churning and I said, "This is not going to be my kind of a meal." But I did get a shell out of the deal!

The shell serves as the sound body for the instrument and I made it. It was kind of a dud. I made another one after it, a wooden one, and it was a little bit better.

You know that first instrument got away from me and came back to haunt me 30 years later. The fellow that had it knew it was my first instrument. I offered to buy it from him but he wouldn’t sell it. He teased me for about three or four years with it and then one day showed up at my shop and asked if I really wanted the instrument. I said, "Yes, I'd like to have it." He said, "Is the offer still good that you will make me a guitar to replace this?" And I did. I made him an East Indies rosewood-body guitar, much like the Martin guitars, and got my first instrument back. I'm looking at it now as we speak. It's hanging right here in the shop. But like I said, it's a real dud. But this is what happens when your heart rules your brain.

NEA: Can you tell me about the designs that you use?

MR. OPACICH: I make seven or eight different varieties in this family of instruments. The one I play, the prima, plays the lead and is very much like a mandolin. A little different tuning but basically almost the same sound. Then we have a thing called a brash, which is a small rendition of a guitar and this is used to play the harmony. Now you can have three of those in an orchestra and you'll have them playing harmony and melody and the third part. There’s also a thing we call a bug, short for bugatia, which is also very much like a guitar. This keeps the rhythm. Then we have another one that looks very much like this instrument and we call it the tamburitza cello. It has four strings and plays the obligato and little riffs. Once in a while if the guy playing it behaves right we let him play a solo. Then, of course, you have the bass violin.

When I started to do repairs, people would bring in wonderful instruments that had been made by the masters. I recognized them as masterworks, so I would make patterns of them in complete detail. I made my own molds for the bending of the sides. I have about four or five different ones. You can come in and request one by Grosell or ask for a Lot. The few makers that I knew always stuck with one pattern, but I was so infatuated with the different shapes and sizes that I figured that was the way to go, to do a number of different shapes and body styles. I do adhere to using good wood like the masters did. I do not like plastics. Some of the newer, younger makers insert plastic and I don't like it. It looks cheap and has a dulling effect on the sound.

NEA: Have you noticed many changes within the tamburitza tradition, both the instrument making and the music? Have you seen a lot of change?

MR. OPACICH: Yes, there have been a lot of changes. Groups from Europe have changed the tuning -- they’ve upped the tuning on every one of the instruments. Where we used to have a G they’ve taken it to A. They believe that it makes a brighter, more appealing, sound. Well, I just don’t buy that. And the instruments made over there are not made of quality wood, even though they have the finest spruce in the world. Stradivarius himself used to get his spruce from Yugoslavia but it's not available to the common folk. The German wood industry buys the wood and doles it out to the rest of the world. It's not cheap. But if I'm putting in 80 to 100 hours building an instrument, I sure don't want any inferior wood on it.

This has never been a money thing with me. I'm dealing with my own ethnic people, the Croatians and Serbians - they are rather frugal and will not pay high prices. Like I say, it has never been a money thing. The money that I do make just goes back into buying more supplies. But it sure has pulled me through some tumultuous times in my life.

I worked as a city fireman for 20 years. I had the misfortune of always working in the ghettos which meant many fires and a lot of troubling situations. But because of this I was allowed to pursue my hobby in the basement of the fire station which sort of took the sharp edge off for me. I did a lot of building in the stations. And when they changed our system to work one day, off two days I was able to do this at home and enlarge the whole system of building.

NEA: I understand you also perform in an orchestra, the Drina.

MR. OPACICH: That’s right. The personnel has changed over the years because of musicians dying or leaving the area, but presently I have five other fellows with me. They're all 25 years younger but I'm very proud of them because they're third generation. They play the instruments real well and sing the songs with correct pronunciation and everything. I'm very fortunate because my playing days are numbered. I had my tamburitza heroes. We had a group of brothers here in South Chicago called the Popavich Brothers who were my heroes and mentors. I used to go listen to them while courting my wife. They had a place in South Chicago and every Sunday we would go there and I'd sit at that front table listening, learning the songs, picking up little odds and ends. They're all gone now so I'm probably the last of the Mohicans as far as the older set is concerned. I'm hoping that these youngsters in my orchestra -- well, they're not youngsters, two of them are 50 and a couple others are in their mid 40s -- I'm hoping that they're going to keep this movement alive.

NEA: Do you think that there are challenges to carrying on the tamburitza music or do you think that it's a strong tradition?

MR. OPACICH: Well, it's a strong tradition and I am so thrilled because about four weeks ago I wrote letters to the five local Serbian churches and I recruited 20 children. I have got someone else to teach them because I've taken on too many things. They've had their fourth or fifth practice and they're learning the instruments and they're already on their fourth song. So I have high hopes that that generation will keep this alive.

NEA: And I can imagine through the years you've done a lot of teaching to help carry on the music?

I'm not a teacher of music. I don't have the patience for that. But I have taught people how to make instruments here in my shop and for four or five semesters I taught an instrument building course at Purdue Extension here in Hammond, Indiana, That was a rewarding experience. And I found out -- I think I was light years ahead of everyone -- I found out that the ladies definitely surpassed the men in building the instruments. My best students were ladies.

NEA: Why is that?

MR. OPACICH: For example, I had one lady come to the class at Purdue. She took the course with her brother who was a musician, a guitarist. Well, she outdid him. I remember the first time I took her to the band saw to cut out the top. Now, the band saw is a very dangerous tool. You can cut your fingers off. You can cut your hand off. I told her where to start the motor and I told her to follow the outside of the line. Most people, even the men, take it very slow. Well, this gal threw this top on there and cut the thing out so fast it made my head spin and I said to her, "You're a ringer. You've had wood shop training." She said, "No, I have not. I do a lot of sewing and the principles are very similar." She made her husband a beautiful instrument and was probably the best student that I had.

I hope some enterprising young man, even as a hobby, will take this on and provide the service of repair work and maybe even building new instruments. But they’re they're going to have to realize from the get-go that it's not going to be a money maker. It's going to have to be a true love.