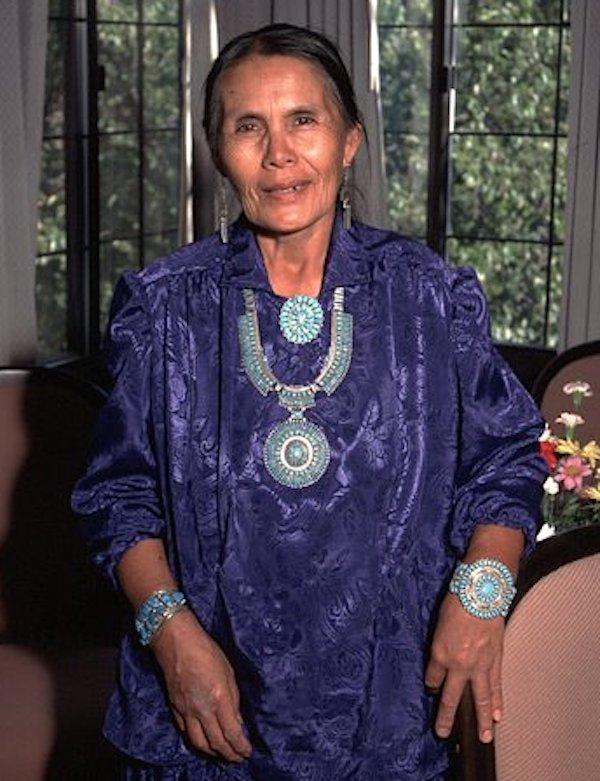

Mary Holiday Black

Photo by James V. Gleason

Bio

Mary Holiday Black was born about 1934 high atop the Douglas Mesa near the northern boundary of the Navajo reservation in Utah's Monument Valley. A member of the Bitter Water Clan, she was raised in a community of traditional Navajo artists and religious practitioners and never learned to speak English. Her mother was a rug weaver and her father was a medicine man. At age 11, she learned to weave rugs from her mother and baskets from a friend of her grandmother's. She learned not only the techniques of gathering, cutting, dyeing, and weaving the willow (sumac), but also the rich store of meaning associated with baskets.

Women in the community have maintained the tradition of weaving ceremonial baskets at the same time they weave rugs to sell to trading posts. Even when rug weaving offered greater economic incentives, Black remained active at basketweaving by passing her skills along to her 11 children. Nine of them and their families are active basket makers.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Navajo basketweaving went into a severe decline. It has been estimated that by the 1960s, only about a dozen active weavers remained, and Navajos had long become accustomed to buying ceremonial baskets from their Ute and Paiute neighbors. But in the 1970s, innovations in basket design, fabrication, and use led by women such as Mary Holiday Black sparked a renaissance of weaving Navajo baskets, both for ritual and personal use and for sale to museums and aficionados.

In the 1970s, encouraged by a burgeoning Native American art market and local traders, Black focused her creative work on basketweaving and introduced several innovations that proved critical to the tradition's survival. First, she stretched the traditional limitations of design, keeping the black-white-and-red color scheme but expanding the baskets beyond the size appropriate for ceremonial use. Some of her coiled-tray "wedding baskets," used in a number of ceremonial rituals, reached five feet in diameter. She also expanded the jar, the other principal extant Navajo basket type, far beyond its previous size.

Later, Black took up the vegetable dyes whose use she had learned from her mother, creating subtle hues and shades not possible with artificial dyes. She introduced new motifs gleaned from prehistoric Anasazi and Mimbres pottery and rock art and from other tribes of the Southwest. She also borrowed imagery from other Navajo crafts, especially sand painting and rug weaving, incorporating both geometric designs and images with religious significance, like the yei-be-chei (supernatural beings), into her baskets. In many instances this pictorial style alludes to mythological scenes, spiritual figures, legends, and scenes from everyday life, leading many to label these creations "story baskets."

Although some of Black's Navajo neighbors were initially uncomfortable with her use of religious imagery, they soon accepted her new kinds of basketry that was more decorative and not intended for ceremonial use. By pushing the parameters of technique, aesthetics, and custom, Black has led a contemporary revival of Navajo basketry.

"There are many basket stories," Black said. "If we stop making the baskets, we lose the stories."