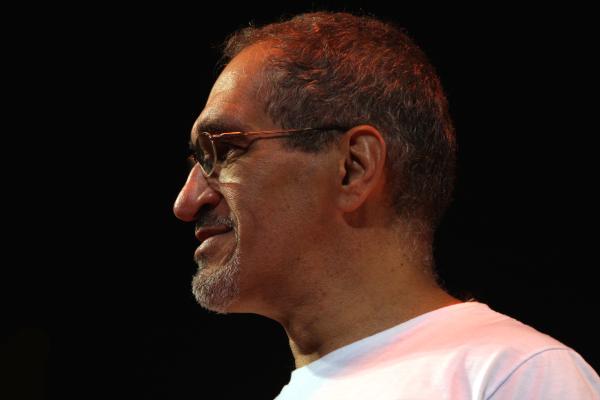

Jelon Vieira

Photo by Michael G. Stewart

Bio

Born in Bahia, Brazil, Mestre Jelon Vieira studied the Afro-Brazilian art form capoeira with tradition-bearers Mestres Bimba, Eziquiel, and Bobo, as well as Afro-Brazilian dance at the Escola de Ballet Teatro Castro Alves. Since his arrival in the United States in the 1970s, Vieira has been at the forefront of promoting and presenting traditional capoeira through performing, teaching, and providing a wealth of knowledge and expertise on Brazilian culture to scholars and historians. In 1977, he founded DanceBrazil, a professional company of contemporary and traditional dancers and musicians that has performed throughout the U.S. and abroad, including performances at the Festival of Vienna, Austria; Spoleto USA in South Carolina; South Bank Theatre in London, England; the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC; and Avery Fisher Hall in New York City. Vieira also founded the Capoeira Foundation in the 1980s to promote Afro-Brazilian cultural forms—particularly dance and music—through educational, presenting, and producing activities. Inherent in capoeira is the music that accompanies the movement. A gifted mover in his day, Vieira still performs the berimbau on stage. A single-stringed instrument that is an integral part of the art form, the berimbau is often referred to as the soul of capoeira. In 2000, Vieira was recognized by the Brazilian Cultural Center in New York City for being the "Pioneer of Capoeira in the United States."

Interview by Mary Eckstein for the NEA

NEA: Congratulations on your award. Can you tell me how you felt when you heard the news?

Jelon Vieira: Very, very happy and very surprised because there are so many great traditional artists out there, and many who are much older than me, too. You know, we have to believe we all very much deserve it and after I hung up I said to myself, "That means that my mission must continue. I must continue what I am doing." Being selected as a National Heritage recipient is an honor for the Capoeira community and myself. This award will help me in continuing my research with the traditions of Capoeira and stay in strong contact with the grand masters. I believe it will help open up new and exciting opportunities for Capoeira in the Unites States.

NEA: Can you describe your earliest memories learning Capoeira and why you were attracted to it?

Jelon Vieira: I believe very much that Capoeira was a spiritual contact because even when I was a kid I sort of did Capoeira. I was always moving around. I was always singing. I heard Capoeira music, but I didn't know it was Capoeira music until later on. I always wanted to be jumping around, and moving around, dancing around.

When I was nine months old, I had a very bad fractures in my both legs, and I didn't walk until I was almost three. A doctor recommend my mother make sure that I do sports where I had to run -- since every Brazilian plays soccer my mother always encouraged me to play soccer. She was always buying soccer balls, but I was not interested. I was always interested in something different. When I was nine years old I was going to get a haircut in the neighborhood where I live and I saw someone playing Capoeira and I was totally taken by it. I stayed there for maybe five hours and I said to myself, "That's what I want to do." I even forgot to get a haircut.

When I got back I told my mother I wanted to learn Capoeira, but at that time Capoeira had a very bad reputation and she said, "Don't you ever say that again. If you ever say that, you're going to be grounded for a long time." So I decided to learn Capoeira behind my mother's back. I discovered someone in my neighborhood that knew Capoeira, a man whose whole family did Capoeira. His grandfather and his father did Capoeira, and he was teaching his kids. But it was too close to my house, my mother could find out very easily. Through a friend in school I found out there was another Capoeira school nearby, but not so close to my mother's house. That's when I met Mestre Bobo and decided to study Capoeira. Every time I came home sweaty and dirty and my mother asked where I had been, I said I was playing soccer.

NEA: You mentioned that Capoeira is a spiritual experience. Can you talk a little bit about the emotions involved in playing Capoeira? What makes it more than a martial arts form?

Jelon Vieira: Capoeira for me is very much a life philosophy. Capoeira taught me respect for life at a very early age. Capoeira gave me discipline. Capoeira gave me a good sense of being respectful, being responsible, and disciplined. And the spirituality I very much believe comes from the music that makes you feel Capoeira. I believe I was meant to learn Capoeira, that it was my mission in life to do Capoeira, teach Capoeira and pass on Capoeira to others. And that's why I say it was a spiritual contact. I believe that my spirit has been a capoeirista in the past, and that I came here to do that.

NEA: You've been credited with bringing Capoeira to the United States. Can you talk a little bit about your early experiences in bringing it here and what the reception was like?

Jelon Vieira: Before coming to the United States I was always fascinated by the African American culture. My first contact with Americans was in my early teens -- there was a group of Americans with some work in Brazil, and they listened to jazz and blues. That's when I got to know the names of all those great jazz musicians and that got me even more interested in the United States. I joined a dance company that was called Viva Bahia, a folk dance company performing Capoeira and we traveled for eight months in Europe, Africa, Asia. At the end of the tour I stayed in London and the director from the group was doing some kind of work here in the United States, and she invited me to come here. This was April 1975, right in the middle of the protests for Vietnam. And I looked around and saw the situation. I also saw how the immigrants lived their lives and I said to myself, "I don't think I want this. That's not what I want for me. I will do anything necessary to give me a living for a while, but I want to work teaching my art." I had to teach it as a traditional art, but also as a martial art. It was hard to convince people that it was a martial art, because the martial arts for Americans at that time was what Bruce Lee was doing. But Capoeira had music, in Capoeira you didn't wear what they did in karate or kung fu –- we wore t-shirts and white pants. People just didn't take it seriously.

I had a friend who was very involved in the demonstrations against the Vietnam War. At that time many of the demonstrations took place in Union Square. My friend said, "Why don't you come and do Capoeira in the demonstrations." I said, "If the police come, I'll be in trouble. You know, I still have a visa." He said, "No, no. It's peaceful for you to come and demonstrate, and a lot of people will get to see Capoeira." And it was a really great way to introduce Capoeira to a lot of people. Also, every Saturday and Sunday through that summer I used to go to Central Park -- I didn't speak English at that time -- and I invited people to join my class. More and more people were getting interested in Capoeira. Then Ellen Stewart at La MaMa Theater saw me and said, "Why don't you teach this to the community, to the kids." At that time there were a lot of Dominicans and Puerto Ricans in the East Village, so I started teaching there.

NEA: What do you think makes a good capoeirista? As a teacher, how do you instill respect for the tradition and what do you look for in a student?

Jelon Vieira: When teaching Capoeira to someone, I want to make sure that person is there to learn Capoeira as a traditional art and that he or she will have open mind to learn the art just the way it is and take it to another level without hurting the fundamentals and the tradition. Yesterday I was having a conversation with another capoeirista about evolution in Capoeira. He asked, "Do you believe in change?" I said, "I believe in change, and things must change, but we have to be careful how we change things." Evolution is great, but evolution has a tendency to destroy tradition for many generations. You have to be very careful. When you evolve in Capoeira, you have a responsibility to your ancestors, to our masters that we're learning from. My master trusts that I will pass this on to another generation without changing it. We can add things, but it can't change.

Every time someone learns from me, I always tell them, "This is lifetime experience. Don't think you come here today to learn it and tomorrow you know it. This is like life. Someday we all go, and we never know everything about life." I don't translate all the songs in Capoeira into English. I don't translate the name of the movements into English. They have to learn in Portuguese. They have to learn the instruments. They have to learn how we make the instruments and the tradition of how we get the instruments. I always tell my students, "Don't rush. Take day by day, because in Capoeira you're not going to learn everything in 10 days, in 10 years or 20 years. It's a lifetime thing." And I tell them, "This year is going to be my 45th anniversary of doing Capoeira, and I'm still learning." Every day I learn something. Every time I go to Brazil and get together with the old masters, I'm still learning.

NEA: What is your favorite thing about Capoeira?

Jelon Vieira: I have so many favorite things in Capoeira. One of my most favorite is gathering and playing instruments with people from a generation older than mine. When I'm playing instruments and singing with them I always feel renewed. I learn something fresh and it shows me that I still have very far to go. I also love teaching, I love passing Capoeira on to other generations. When I'm teaching, my students always say, "Mestre has a time to start a class, but he doesn't have a time to end a class, and that's what I love about him." For me it's like a trip. I don't like to rent studios just to teach a class, because you always have a schedule to follow. In Capoeira you can't. I teach Capoeira just the way I way I learned it from my Mestre, in a very natural environment.

And I love playing the berimbau every morning in my house.

NEA: Why is it called "playing" Capoeira?

Jelon Vieira: The slaves that came to Brazil from Africa had to camouflage Capoeira. Capoeira was the only weapon they had since they were forbidden to use any kind of actual weapon. But it was not just the physical. Capoeira is not just physical, it is mental. Sometimes they had to do Capoeira in front of the Portuguese overseers but they had to make it look like a dance. They had to pretend that they were fighting. The word "playing" comes from the word jogo. We don't say fighting, luta. We don't say luta, we say jogo. Jogo is playing. "Oh, what are you doing?" "Playing Capoeira." But doesn't matter if we play a hard game, or if you play an easy game, or if you play a friendly game. If they made it look like fighting it would be too obvious for the Portuguese. Many times they'd ask the African, "What are you doing?" "Oh, we're playing Capoeira. We're playing." It took awhile for the Portuguese understand what "playing Capoeira" really means.

NEA: I imagine there are a lot of improvisational elements to playing Capoeira. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Jelon Vieira: It's the tradition of the game. When I teach Capoeira it's like teaching someone a language. If you come to learn Portuguese from me, I will teach you the the whole alphabet and the sounds. Then I'll teach words, then I'll give you a phrase. Then I encourage you to go out there and have a conversation with someone using the elements I have taught you. Now you're on you own, you have a mind, you're smart, you have to make your own conversation. Capoeira is a dialog between two people. It's Q&A. We improvise because there's a lot of thought going into the game. I have to trick you, you have to trick me. It's like playing chess. When I watch a basketball game and watch the way the players play, I always think about Capoeira because it's all about thinking, it's all about tricks. Capoeira is all on the defense side. Capoeira is not an attack art form, it's always on the defense side. I'm always trying to set you up. That's why it becomes a game, because I'm trying to set you up, you try to set me up. You give me a bait so I can fall for it, but I'm also putting a bait for you, and that's why it's a game. That's how we play a game, trying to fool you, you're trying to fool me, I'm trying to overpower you, you're trying to overpower me.

The central idea in Capoeira is that you have to know the person inside of you. We all have someone that we talk with, with our own self, and we all have to get to know ourselves. And through the game of Capoeira I‘ve gotten to know myself, and gotten to know my limitations. I understand and also respect how far can I go, how far can I push someone. You learn to respect danger through the game. I have taught a great deal about the good things and the bad things in life through the game of Capoeira.

NEA: What has kept you playing Capoeira through the years?

Jelon Vieira: I started to believe at a very young age that Capoeira is my life and Capoeira is my strength. Capoeira is my life philosophy. Capoeira is what's given me a base and a strength to see the world. It teaches me tolerance for things that I can't change. Capoeira gives me sensitivity, gives me love, gives me the understanding that people are people regardless their background, their gender, their race. We all should come together and that's the power of Capoeira, bringing people together. And I have been very responsible to my Mestre's knowledge -- I feel like I must give continuity to his mission. I wish this award that I'm receiving from National Endowment for the Art could be given to my Mestre, so I am dedicating this to my Mestre.

I grew up without a father. My mother was the man and the woman of the house. My mother was an exemplary model of what a woman should be, because she was so strong. And Capoeira gave me the message which I believe my father would have -- make sure to grow to be a man. And Capoeira teaches me how to work on myself to be a better human being every day in life.