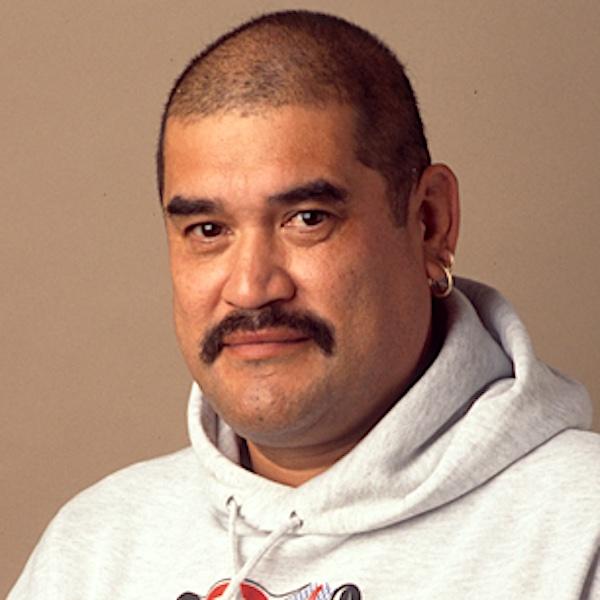

Gerald "Subiyay" Miller

Photo courtesy of the artist

Bio

Gerald Bruce Miller, known as Subiyay in the Skokomish tribal language, has dedicated his life to learning and passing along the knowledge and artistic skills of his elders. The Skokomish, Coastal Salish people who live near the Puget Sound of Washington State, appointed Gerald as their tribe's cultural and educational director in the early 1970s. Miller is recognized as a master of Skokomish oral traditions, as he is the keeper of a repertoire of over 120 traditional stories, many of which take days to tell. In addition, he maintains a large repertoire of songs and dances related to ceremonies and rituals. Miller helped revive the First Salmon and the First Elk ceremonies and, following his initiation in a longhouse in 1977, brought winter ceremonies back to his people. A visual artist as well, Miller makes baskets, carves ceremonial masks and poles, and makes regalia or ritual dress. In 1993 he received the Washington State Governor's Heritage Award and in 1999 was named a Living Treasure by the Washington State Superintendent of Public Instruction for his lifetime of work teaching young people.

Interview with Mary Eckstein

NEA: Congratulations on your award. What was your reaction when you heard that you had been picked as one of this year’s fellows?

MR. MILLER: I was very surprised. I never really thought about getting an award for what I do, but it was exhilarating at the same time.

NEA: Tell me about how you were introduced to the tribe's traditions?

MR. MILLER: I was one of 15 children and grew up in an extended household of 25 members -- 14 brothers and sisters, maternal grandparents and a maternal uncle, a paternal grand-uncle, and an assortment of other extended family that lived with us from time to time. A lot of what I grew up knowing was the result of the teaching of my grandparents who were the head of this extended family. My great-grandmother, who was born in 1861, lived just down the road and we spent a great deal of time at her house hearing stories. My brothers and sisters and I would go over at the end of the day to receive traditional teaching, though we didn't realize what it was at that time. We just enjoyed listening to her stories. Two other of my mentors were born in 1881 and were my teachers up until the time they passed away. A majority of my most influential teachers were born in another time.

I just assumed that everybody knew what we knew. I didn't think it was important knowledge until I moved away from home. A great interest in American Indian art and culture was developing at that time, the ‘60s and ‘70s, and it was then that I realized the value of what I knew and that not everybody knew what I did. I left home to go to school in 1963, then went into the army, and then back to school where I began to write and create artwork based on the knowledge I had received. And by the time I gave the language much thought there were 52 speakers left. By the time we began to document the language it had dropped down to five. Now I'm the only one. My image of this, thinking of my teachers and my source of knowledge, was as if I was looking at the aboriginal forest full and lush, then time passes and half the forest is gone, time passes again and there's just a few trees, and finally there's just one tree standing. That's when I decided it was extremely important to document all this for my community members in the future and to make the stories and the language accessible to anyone who’s interested through modern technology with the computer and all that.

I've been training for over 20 years to ensure that the arts I am well known for are handed down and expanded on in my lifetime. I have the satisfaction knowing that when I leave this world the knowledge and the gifts our ancestors developed and left will still be here.

|

|

NEA: What kinds of things are your apprentices working on?

MR. MILLER: I have some working in herbology, some working in overlaid twine basketry, some working in oral tradition, some working in the language, and some working in regalia.

NEA: Could you talk about the responsibility of being the cultural and spiritual leader of the tribe?

MR. MILLER: It's a very demanding role and something that I'm obligated to fulfill during my lifetime. In our language we would call it "widadad." Widadad means “cultural teacher.” It’s the knowledge of the correct way of performing rituals and songs and ceremonies, and the times of year for the ceremonies and the ritual preparations. The preparations for these ceremonies have to be done in specific ways and I'm handing that down to different apprentices so they will be carried on. It's a very demanding role but it's a responsibility that has to be carried out.

NEA: What are the oral traditions, the stories, about?

MR. MILLER: Our stories are like the Bible. They begin with creation and go up into times of teaching. The animal people were given the responsibility of experiencing all the trials and tribulations of life and leaving behind the stories of their lives to serve as teachings for the humans who were to come. The stories would give us the measurements and experiences to look at for situations in life, including lying, stealing, adultery, murder, and all the different structures that form our society and our moral and ethical patterning.

NEA: Is it difficult to carry on these traditions in the modern world or do they still resonate with the community?

MR. MILLER: Sometimes it's disappointing that not as many of the youth that I'd like to work with are interested in carrying on the traditions. But there are some and those are the ones I focus on. There is a growing number of young people in the community now interested in picking up the art of weaving and basketry, for example. That's why I feel it's important to use modern technology for all this data.

We went through a great effort by the government to de-Indianize us and destroy those skills among our people. We suffered from several generations of forced acculturation where the Indian agents taught us that our traditions were wrong and demeaning and belonged in the past. That impeded us. But they’re beginning to be appreciated as part of our cultural identity again.

NEA: I know you spent a lot of time developing the Indian Early Education Project. I was wondering if you could talk about the philosophy behind that project.

MR. MILLER: The central philosophy of the teaching is that a child's character and patterns of social behavior and attitudes develop by the age of four. It's the embryonic stage of creating the life-long personality. The greatest influences in our aboriginal culture were the grandparents spending time with the children of that age. With this project we dealt in what we now call right hemisphere of the brain teaching style which included group learning and oral traditions, visualization and many of the things that I tried to incorporate into the formation of early childhood education that would apply to the learning styles of our children.

NEA: How important, then, have these traditions become for the tribe?

MR. MILLER: There are those who look to improve the lives of the tribe through non-traditional means, through economic development activities like real estate and casinos, and overlook the maintenance of the traditions. But the traditionalists can't really compete with the economic contributions of these other things. So it's two different aspects. On the one hand we have to look for economic benefits but on the other look for the satisfaction of the maintenance of our traditional contributions. Unfortunately, to the younger generations it's more important to economic base and that's the same anywhere in the world.

NEA: What advice do you have for young apprentices doing the work that you're teaching?

MR. MILLER: You've got to really love what you do and not be concerned about making a living. That has never been an important part. It was the love of the culture that helped me persevere through everything. I gave up some very promising careers in order to do this -- my concern was for the generations to come rather than myself. It's harder to find this drive in younger people but I think it's our responsibility as elders to nourish this appreciation of what our ancestors had to offer and to learn something about it.