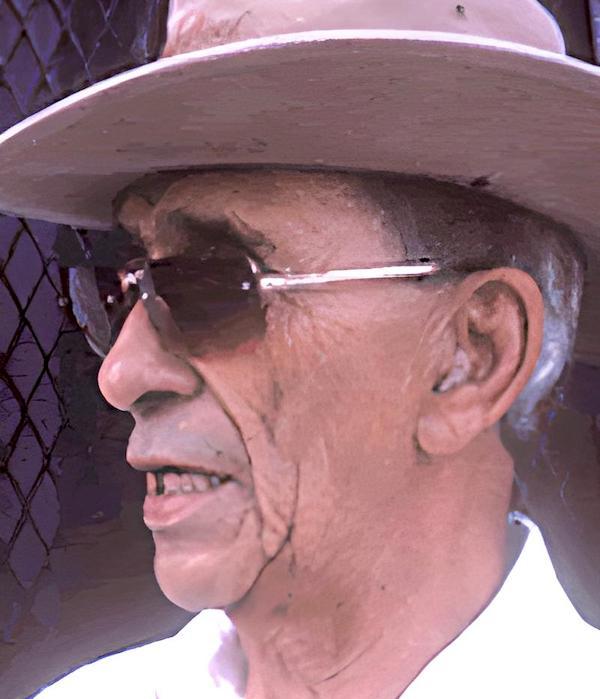

Earl Barthé

Bio

Earl Barthé is a fifth-generation architectural artisan whose great-great grandfather came to New Orleans from France, via Haiti. A self-identified "Creole of Color," Barthé executes decorative plaster and stucco work that reflects an array of French, Spanish, Anglo-American neo-classical, and African American aesthetics, reflective of the historic architecture of New Orleans. Barthé notes that 99% of the past generations of his family have worked in the building trades. Even his sister, who went on to be an international opera singer, worked at plastering in her younger days. In fact, he notes, "Plastering and music sort of rhyme." He adds, "You run the mold and then you place the dentils, those little square things that are cast and placed in the mold. It all has to be in tune."

The work of Earl Barthé was featured at the New Orleans Museum of Art in an exhibition titled Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts in New Orleans (2002-03). An art critic writing in the Times-Picayune pointed out in a review that the exhibition reclaimed the Renaissance-era connection between sculptural architectural ornamentation and skilled craftsmanship that had nearly been lost in the United States. In 2001, Earl Barthé and his family were featured as master artists at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. Today, Barthé continues to teach young people these endangered skills and has initiated his own apprenticeship program in decorative plaster and stucco work.

Interview with Mary Eckstein

[Editor's note: The interview with Mr. Barthé took place in July, 2005. Due to Hurricane Katrina, he is currently living in Houston, Texas.]

NEA: Congratulations on being named a National Heritage Fellow. Tell me how you felt when you heard the news that you had gotten the award.

MR. BARTHÉ: I think my name was submitted a couple of years ago and naturally I've been looking and thinking, well, maybe this year. So when I received the letter I was elated. I was really was. I couldn't believe it.

NEA: How did you get started in decorative building arts?

MR. BARTHÉ: The Barthé family is one of the oldest plastering families in America. We go back to the early 1800s. My father was a plasterer, his father was a plasterer, his uncles and everybody else were plasterers. The Barthé children just knew they had to be plasterers. Daddy didn't want me to be a doctor, a lawyer or an Indian chief. He wanted me to be a plasterer. I've been plastering all my life.

When I very young –- oh, seven years old - Daddy would come in after working on a Saturday tell my brother and I to clean the tools. He would leave pennies and nickels in his toolbox and say, "Whatever you all find, that's for you." So we'd dig in that bag, cleaning the tools and looking for them pennies and nickels. We realized later that he was training us. He would say, "Earl, give me that pointing trowel." And I'd say, "Pointing trowel?" He would pick it up and say, "You see this little tool. This is a pointing trowel. When I ask you for that that's what I want you to give me." Then he would tell my brother, Harold, "Harold, give me the hawk." That was his way of educating us. There were no apprentice training classes at that time.

In my day all the churches, cathedrals, schools, and libraries had a lot of historic plastering. All the main churches in New Orleans have molding and medallions. And that's what I come up with, with that type of work. Daddy came up with that and his father came up with that. When you walk into these cathedrals and you look up and see all that fancy work, well, somebody had to do it. In New Orleans you can bet the Barthés had a large part in that.

NEA: How does one become a good plasterer?

MR. BARTHÉ: Coming from a family of plasterers helps a great deal. When I was a youngster learning the plastering business, plasterers would build one another's homes. On the weekend Daddy would take me to work on another plasterer's house. And one time, he said, "Earl, boy, you're not doing good. Teal's son is much better than you. You hear me?" He sent me home. I went home crying and told my mother. She said, "Oh, but your daddy don't mean it." I said, "Oh, yes, mother, he told me that." But the next week I went out again and when getting a drink of water or something, I overheard him talking to another man about me, so I stopped. And guess what he said? “"Mr. Teal, you see that Earl? He's going to be a good plasterer." I backed off. I backed off then and I couldn't stop. I went home and I told my mother. "Well, that's daddy's way,” she said.

I never told him I heard him. That was Daddy's way of training. They didn't have schools for this and that was his way.

NEA: I understand you were very involved in the politics of plastering in New Orleans.

MR. BARTHÉ: In 1954, I was elected the union representative for the plastering industry in New Orleans. I did that for six years and then my brother took over. I went into the contracting business and my brother represented the industry from 1960 to 1972. he died in '72 so they asked me to come back. I did and stayed there until 1986 when I retired. So he and I ran the union from '54 to '86.

You know, while the Barthés are well known here in New Orleans, there were probably a hundred other families just like us involved in plastering. So any building in New Orleans built during that time we had something to do with or contracted the plasterers for. I furnished 193 people for the Superdome. That was one of my prize projects. My daughter Cherry even worked there, after it was finished - we had to have plasterers do maintenance work. She works with me today.

One very interesting historic note. My great-great grandfather, Leon Barthé, was a free man of color and a master craftsman. He was the father of Antoine who had two sons, Antoine II, and Peter. Peter was instrumental in organizing and training plasterers - generations of plasterers - with a friend by the name of Sam Ball. Together they organized the Plasterers Union in 1901. In 1901, like the rest of the south, New Orleans was highly segregated. But Peter and Sam organized an integrated union in 1901. Can you imagine?

NEA: Has the plastering tradition changed much over the years?

MR. BARTHÉ: Like I said before, plastering families wanted their children to follow in their footsteps. You don't have that as much now. I have grandchildren who are nurses, doctors and things like that. It would be kind of difficult to say, "I want you to be a plasterer."

The other big change came in the early '70s. Sheetrock. I noticed they were using sheetrock instead of plaster. Between you and me, we can train somebody to do sheetrock in six months. It takes three years to train a plasterer.

To become a journeyman in my day it took four years. Today it takes two years. I can take any guy off the street, any guy I see, and in six weeks I can make him a master synthetic finisher. Don't think I'm an old fuddy duddy now because I'm not. I understand the economics.

Today we have subdivisions and people building million dollar homes, using all sheetrock, no plaster. We just finished one for a doctor. He had some imitation decoration on the front of his house but the termites got to it, so he finally decided he wanted conventional plaster. You know, if you're going to spend a million dollars for a house, you can spend $50-75,000 with me and you'll have an interior like you've never seen before. Oh, man, I could go wild with that.

NEA: What's your favorite thing to do when it comes to plastering?

MR. BARTHÉ: Crown moldings and medallions. They add so much to your home. I make special medallions for the entrances, ones for the bedrooms, and others for the kitchen. They have a lot of fruit and things like that in them. That's what I like and that's what I'm doing today. I don't do regular plastering.

NEA: After all these years working in this craft, what advice do you have for young plasterers?

MR. BARTHÉ: Take pride in what you do and protect your job. Be sure you give a good day's work for a good day's pay. And whatever you do, try to do your very best and try to improve on it everyday.