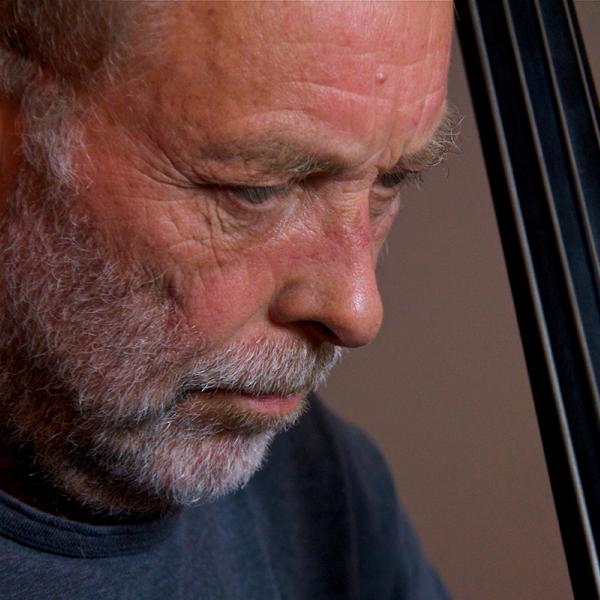

William Wegman

Transcript of conversation with William Wegman

William Wegman: I never really knew what I was, where I was and what category I would be in. I remember the first time MoMA bought one of my works it was a photo but it was bought from the painting department and it was put in with painting. Because I guess John Szarkowski, who was a great person but he didn't really, I think, accept kind of the sort of post-modernism that I might've represented. I wasn't like real photography, so it was the painting department that was interested in my work and not the photo department.

Jo Reed: That was photographer, painter, videographer and owner of some photogenic dogs, William Wegman. Welcome to Art Works the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation's great artists to explore how art works. I'm your host, Josephine Reed.

Moving fluently among drawing, painting, photography, and video, William Wegman is hard to categorize. A conceptual postmodernist artist with a funny bone, Wegman is probably best-known for the photographs and videos of his Weimaraners in unusual poses and in costumes that look like surreal sight-gags. Wegman's early video works, many of which star his dog, Man Ray, combine minimalist performance with low-tech video to create unlikely moments of absurdist comedy. Wegman and Man Ray caught hold in the popular imagination. In fact, The Village Voice named Man Ray 1982's "Man of the Year," which was fine with Wegman since he always thought of the dog as a collaborator anyway. But don't let Wegman's easy-going humor and sense of the absurd fool you. His list of accomplishments are legion. Always an innovator, William Wegman was one of the first artists to use video as an art form. Since the late 1970s, he has received international acclaim for his work in photography. Wegman exhibits in shows around the globe. His work is in the permanent collections of many museums, including the Walker Center, Minneapolis, The Whitney Museum of American Art in NYC, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, and the Australian National Gallery. His photos and videos have also been a great popular success, and have appeared on television programs like Sesame Street and Saturday Night Live. He's branched out to create a series of children's books based on fairy tales and a number of books on dogs. In 2006, the Brooklyn Museum explored 40 years of Wegman's work in all media in the aptly titled retrospective William Wegman: Funny/Strange. In a review of the show, the art critic for the New York Times said of Wegman: "Dogs or no dogs, Mr. Wegman is one of the most important artists to emerge from the heady experiments of the 1970s."

I spoke with Bill Wegman in his spacious loft in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York. Before we settled in for a talk, graciously showed me around his various studiosâone for painting, photography, video. Two of his three dogs, Bobbin and Candy, settled down very nicely, but one-year-old Flo has a lot of energy and you'll hear her from time-to-time, especially close to the end when her patience has clearly worn thin! I was very curious to know how Bill began his working relationship with with his first dog, Man Ray.

William Wegman: Â He was six weeks old when I got him in 1970 from Long Beach. I was living in San Pedro, but teaching in Long Beach for one year. He persuaded me to do it. He was around me constantly. I couldn't really keep him out. I'd go to my studio and I'd tie him up at the corner so he wouldn't start chewing things that I was lining up on the floor. And he would whine. So it was much easier to let him chew the things and then photograph him doing it or videotaping him. And he just loved games, so he was a great video dog. And he seemed to respect work. Like if I was working on something with him, he knew that it was important. I kind of imagine it's what a hunting dog does when you're cleaning your gun and you're getting ready to go to your pickup truck and go look for partridge or something like that. The prep that went into the video, setting up the equipment, the way he was always on standby as I thought, and I think that was really great. Also being by myself around him was really good. The fact that I didn't work with a crew, that I didn't quite know how to hook it up, that it took time and it was kind of simple and calm is all part of the process. So when we jumped in and he's on, he starts to, and it was really mind blowing when he first did this, he starts to look into the camera. Look at me and then he looks into the camera. "Oh, we're doing one of these. I know what we're doing now." Â And so he goes along with it.

Jo Reed: When you started doing video, artists weren't doing video.

William Wegman: Getting involved in video seemed just electric and surprising and really something that I felt that I really discovered it. I didn't really know other artists that were using it. It was just something that happened. I didn't really necessarily calculate this as a career. But I remember borrowing some equipment and bring it into my studio when I was a visiting artist at the University of Wisconsin. And I set the stuff up and immediately had a sense of how I could use it. And it was something that just came to me. I made seven reels of film, one a year, from '70 to '77. So part of the problem, why I didn't continue, was switching from black and white to color. I couldn't figure out how to deal with color video. Then you needed tremendous amount of light. It made the studio hot and unpleasant back then. Now, every camera records color simply and easily and there's none of that problem. But in the beginning with that early video, it really made the act of making color videos a torture for me. And coincided with me, started to work with Polaroid 2024 camera in Boston. So that kind of took over as my major medium by '79, '78-'79 I started to use that. And then I didn't do video again til '98 and I made 2 years of video again there.

Jo Reed: Can we talk about an early video you did called "Spelling Lesson" which I've seen innumerable times and cracks me up every time? How did this come to be?

William Wegman: Well, it was made in East Hampton in a studio that a friend of mine's father had relinquished and given to us. It was a factory building. New York was torturous. I had this miserable little loft on 27th Street that I was subletting and my dog Man Ray, who'd just moved from the beach in Santa Monica, was tortured by 6th Avenue and 27th Street rather than being at the beach. So I kept thinking of ways to not be in New York. But I was a New York artist, so had to kind of dart back and forth. This piece was made in East Hampton. The idea came to me on the way to the Everson Museum where David Ross was curating a video show, the first video show, I believe, in '73, possibly, something like that. I think the Everson Museum was on Walnut Street, but before you came to Walnut you went to Cedar Beech, and I was sort of saying it out loud. And I said, "Beech."Â And Man Ray just went berserk from the backseat of the car when I said, "Beech."Â But it was beech like the tree, not the ocean. And so I went back to New York. I dreamt up that piece where I was correcting his spelling, B-E-E-C-H and not B-E-A-C-H. And he had such a fantastic connection to me. Everything I said. There were certain words that he would practically unscrew his head over. Beach was one. My father, who he adored, George, was another. Every time I'd say, "George," his head would unscrew, because George lives and still lives in the country in Massachusetts. So there were these key words. For some reason it took me a while to figure out, because I'd lived in Milwaukee for a while, what Milwaukee was, but there's the word "walk" in Milwaukee.

William Wegman: And so every once in a while he'd start getting animated. It was sort of how he picked up on the language.

Jo Reed: And when did you move into photographing him?

William Wegman: I photographed him simultaneously. And I think that both video and photo were disciplines that were very new to me but ones that I felt were complimentary. With video, it was pretty much just jumping in front of the camera and dangling things there, whether it was the dog or my finger or a light bulb or whatever it was. With the photos though, I made little sketches sometimes and then would assemble them. So that came out of installation art I had been making in Wisconsin where I felt that actually I was kind of influencing the installations so they'd look better in the photograph. And then it occurred to me that what I really should be doing was making photo pieces, as they became known as, rather than documenting performances or installations. And I also liked the power aspect of being able to publish or broadcast, which both video and photography was capable of. Your work could be in a magazine and would be understood the same way whereas a performance you had to kind of be there or installation, you could only see an aspect of it but not the whole thing. I felt like when you were looking at one of my photos in a magazine, may not be as crystallized as it would be in your hands or on the wall but for me would mean the same. So that was a major thought I had about it.

Jo Reed: I want to talk about Man Ray as your subject. The portraits you did of him with the Polaroid are just extraordinary.

William Wegman: That was towards the end of his life. He was nine years old. And first we would go to Boston. That's where the camera was, in Cambridge, and so I would stop at my parents' house and pick up possibly some of my mother's golfing clothes. Or when I was in Boston I'd stay with my friend Betsy, a fellow artist, and borrow some of her stuff. And I didn't really want to make these color pictures, but I found a way to and it really did sort of made me think in terms of the beautiful again rather than just the cool.

Jo Reed: Yeah. That's a dilemma, isn't it?

William Wegman: It is, yeah.

Jo Reed: Getting trapped by the cool.

William Wegman: I took an amazingly beautiful photograph and I didn't trust it. I wanted to deny it. But then I decided, "Okay, that's fine."Â I didn't go try to do more beautiful ones, but I had to accept that this one was beautiful. Was a picture I'm thinking of Man Ray where I put false eyelashes on him and he was posing next to an old student of mine when I was teaching in Long Beach, Hester. And they were shown in profile and somehow the joke was they both have big eyelashes. But you don't see that because it didn't register. So the way I made the work, and it wasn't a successful photograph, was absolutely stunning. But it looks like, in fact, it was on the cover of Artforum. It was one of their most successful covers, Ingrid Sischy told me. And it was better than me, the picture, and that's what photography gives you sometimes by accident, an amazing moment. And wasn't one at the time I could've dreamt up, "I'm going to do this powerful picture of and the Beast."Â It looked very masculine-feminine. It was like a double profile rather than a joke about the eyelashes.

Jo Reed: I understand being open to what's unexpected, but how do you conceptualize what you're going to do with the dogs before you start clicking the camera.

William Wegman: Lately, since I been working so many years with dog, I always start with the same thing.There's always these white pedestals around. Put the dog on or in the box and start from there. <laughs> And then bore yourself silly and go on or find a new way to do a dog in a box.

Jo Reed: <laughs>

William Wegman: And it helps them. They like to know what they're doing, that they're here at this place rather than just generally over there. My dogs aren't so well trained where I'll say, "Go over in there and put one foot up."Â There are dogs that do that kind of stuff, but I go over and I set them and it's almost a little dance. It's very physical where I'm holding them and I'm playing with their pose and so forth. So they're very accommodating. My dogs, I think, because they're gray, have given me such latitude also, that sort of neutrality of them where they can become a Dalmatian or a poodle or a space modulator or a rock. They can transform because of this neutral tone they have, this blackness.

Jo Reed: Well, I also think not only is it the neutral tone, but it's the coat, the short fur, the sheen of that coat and what it does with light is so fascinating to me.

William Wegman: I think so too. And I remember, especially it came out in the Polaroids that be photographing one against a red background and the dogs look kind of pink and then if it's yellow they look like yellow Labs almost. They're really like little mirrors. When they run in the woods they get kind of purpley if it's a blue sky out and they're running through the woods. They look purple. So they do reflect this light in a really nice way.

Jo Reed: Fay Ray was your second dog you had that you photographed a lot, and she became a star in her own right. How different were Man Ray and Fay Ray?

William Wegman: Very. Fay was more of a thoroughbred. Man Ray might've been not even a pure Weimaraner, although I'm told he was a blue Weimaraner. So he's darker. I got him at six weeks. I got Fay at six months; and she came somewhat, I wouldn't say damaged, but when she met New York City, it wasn't a happy moment. She was terrified of those roll down gates, people kicking trashcans, and in the studio light stands, had to-- really if we were doing any kind of film work around light stands or if we were on a talk show, if the band was playing too loud, she'd look petrified, she looked sometimes like a helicopter that's been shot down and is spinning on the ground, foaming and spitting and spitting. And Man Ray was so solid and impervious to any kind of--

Jo Reed: He seems laconic.

Bill Wegman: Yeah, and he wasn't ruffled the way she was. But she had this love of working at Polaroid. She just craved the strobe light, the praise. She liked it if it was difficult. She'd like-- "wow, look at that."Â She really loved hearing that.

Jo Reed: What made you start thinking of children's books? And I'm thinking about the fairytales. What made you branch out?

Bill Wegman: Well two people I knew, Carol Kaczmarek [ph?] and Marvin Heipherman  said, "How'd you like to do a children's book, fairytales or something like that?" I said, "Okay." So I did that and the first book that I chose was Cinderella because it seemed to be a parallel with when you adopt a dog, you become their step-mother, and you're either their fairy godmother/father or the evil one. You're taking them away from their home and you're putting them in a new home it seems. It seems like a perfect story. The other one I liked was Little Red Riding Hood; because I live in the woods in Maine, and that appealed to me. And the idea of the transformation of a dog into a grandmother or vice-versa seemed totally what I could do. So I did those two. They were kind of conceived simultaneously. Cinderella came out first but I think my first, the one I really wanted to do, was-- and the easier one-- was Little Red Riding Hood. I knew a dentist who made false teeth for one of my dogs to become fangs. He actually made an appliance which this dog wore; and that was a highlight reel for me.

Jo Reed: How did the dogs respond to their props?

Bill Wegman: Yeah well Fay had to be-- since she was so vulnerable, I had to be careful of certain things. She didn't like to sit next to plants-- don't ask me why-- and she didn't like things that were metal; and she didn't like-- she didn't not like but she didn't particularly like sitting next to other dogs, other than her daughter, Batty. And Batty was completely opposite. She was-- I mentioned this before-- she was like narcoleptic. She would fall asleep on the set, and super-relaxed. She'd get very quiet, where Fay would get kind of bug-eyed. And Batty's sister, Crooky, who is in several of my videos for children, she had kind of the opposite and complementary to Batty. She was also bug-eyed and-- the bomb's gonna go off.So I had these characters that had different personalities; which I really liked working with. They are really a muse. When they're just on the couch over here and you look at them, and the way the light falls, or certain things that happen-- the stretching she's doing now; all of those thing, I just love being around them.

Jo Reed: How did you manage to make so many photographs and videos of dogs without it falling into a gimmick?

William Wegman: Well, I don't know. The real danger, I suppose, was when I started to make books, children's books and so forth, and that happened with Fay, my second dog, where I made her tall one day at Polaroid. The camera's vertical and I was trying to get things up there. So I put Fay on a pedestal and I was wrapping fabric around her, so she was some kind of a column. And my assistant Andrea was talking to me from behind and helping keep Fay up there. And it looked like her arms became Fay's and it kind of was startling and funny and eerie and not terribly cute like dogs dressed up tend to be. So I thought it was okay since it was menacing somewhat. It looked more like creatures from mythology rather than some cartoon or circus. So I kind of went with that. But I think then it became like a one-liner about me. "Oh, he's the guy that dresses up dogs," you know, "The guy that dresses up those dogs." And that's the way people I'm sure still remember me even though it was just a small part of the work. Man Ray, I never dressed him up as a person. I dressed him up as an Airedale once and a frog and an elephant, or just as a dog, another kind of dog sometimes. But with Fay, she became this creature that became the evil stepmother. She became like a Joan Crawford character. She became these personas. And then I'd turn her back into a caterpillar sometimes. Then when I had multiple dogs, then I had all of these characters. I had first Fay and her daughter Batty and her son Chundo and they became sort of the superstars of my children's books. And then it became, the press became, they're go on book tours, there'd be newspaper articles, there'd be spots on talk shows. And that made this kind of work kind of almost work against them. The art world, in a way, it became I think, for some, not all, but, "He's no longer an artist. He's doing these commercialâ¦"

Jo Reed: He's popular.

William Wegman: Yeah. And so I could understand that, in a way.

Jo Reed: Don't you think-- or I'll just tell you what I think and you can--

William Wegman: Sure, please. <laughs>

Jo Reed: --tell me if you think it. <laughs> But don't you think, in a way, what you were doing was sort of breaking down that dichotomy between high art and what's popular? It seems to me throughout your career, something you've always been concerned about is having your work be accessible to people.

William Wegman: I really did. I was very stymied right before I had this sort of breakthrough in video and photo. I was putting interesting things on the wall like mud and hair and rotting carrots and I remember a fellow artist came into my studio and there was debris all over the floor and he said looked really great. And it did. And that was the problem. The stuff on the floor looked really good. But I didn't do it on purpose and I really felt like I needed to control every aspect of the work, that I needed the intention there. I needed the clarity. And one way of knowing whether this clarity was being received was if someone responded. And laughter is one way where you really know someone gets it, and I think that must've really appealed to me, the fact that someone just fell down laughing. But I wasn't really necessarily after humor. But it certainly did sort of pat me on the back, I guess.

Jo Reed: Well, it permeates a lot of your work--

William Wegman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: --wouldn't you say?

William Wegman: I think I have a funny bone. And I notice the video pieces, most of them are funny. The ones that are interesting I'm less interested in, I suppose. The photo pieces one tends not to laugh at. The drawings that I started to make in my third year of my serious work, I suppose, by '73, some of those are really funny, I think. And it has to do with drawings can be funny in a way paintings never can be, because of the weight of history that they have. And if they are funny then that's complicated by their physicality, whereas a drawing, it's physical, but it also is not. And I think that's purer and funnier and whips into your head and stays there where a painting gets into your head but it's much more powerful to stand in front of it and receive it that way. That's why it's always refreshing and rejuvenating to go to museums and stand in front of the de Curaco that you see all the time or whatever it is. You start to live it in a different way.

Jo Reed: Now tell me when you returned to painting, to actually painting on canvas again.

Bill Wegman: Sure. I was a painter. I stopped painting in my first year of grad school. I kind of bought into the fact that painting is dead. And so when I started to have dreams that I was painting-- I think it was in my mid-40s; or even late 40s-- I felt like I really had to do it. But I went back to my last painting that I did in high school; I painted pictures of the Breck girl, which got me accepted at Mass Art. It was like he's good at drawing. So I made these paintings as if I never went to art school. Also I'd been drawing too. So it kind of looked like my drawings kind of come to life. They were a little scrappy and funky I suppose. Holly Solomon, who was my dealer at the time, was so in love with painting, to begin with, that she-- she just was wonderful to show work to, and encouraged, I guess. And so somewhat embarrassed about returning to painting, but knowing that I really loved it; but also didn't know how. I thought I knew how but I didn't. I had to kind of learn how. So I really had moved far away from my drawings into doing paintings the way painters would paint. My first ones were, I'd think what's a suitable subject for painting? It's got a whole different-- there's something different about painting than drawing and photos, and you have to think about what it should be. So I think one of my most brilliant decisions was that it should be on canvas and it should look like Cézanne. So I did a painting of tents; which were of canvas on canvas, but they looked like Cézanne. So. And there are all those kind of funny but historical notions about them. And since painting takes time, sometimes, there are some things that you daydream about while you're making them.

Jo Reed: You had a big retrospective in 2006: "Funny Strange."

Bill Wegman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: Which it was a perfect title.

Bill Wegman: Yeah. Thank you. That was based on one of the drawings that I made for another show in Boston actually; which I've never told anyone 'cause it seemed like the wrong thing to tell someone. But when David Ross was at the ICA in Boston, I believe it was, he had a show which he titled "Funny Strange", and I made a poster for it. And that show I think was interesting because it showed every line of my work in a-- pretty well flushed out: photos, videos, paintings, they all seemed to be established. Whereas the show that I had at the Whitney, in '87 I think it was, it looked almost like well for this class he did these and for this class that. But the time period made the selection process, and it seemed more- had more weight, every line. I think of myself as having these four lines: the drawings, the paintings, the videos, the photos. And those are the things that I do, and they're each branch, each chapter is major for me. I don't weight one higher than the other.

Jo Reed: I think for many people it was really the first time they got a glimpse of how wide your net is.

Bill Wegman: Uh-hum. Yeah, that's what I saw and liked about it too, that it seemed to mix it together. It seemed to mix it together and it seemed all okay; whereas it didn't used to seem quite so okay. As I said before, it looked like I did it for this class, and then for this class I did this stuff and so forth. There it seemed to hold up.

Jo Reed: Tell me what you're working on now.

Bill Wegman: Well I'm working on these paintings with postcards. And I've been doing that since '90-something-or-other; '3 was the first time I stuck a postcard to a piece of paper and started to extend it. But now the latest ones seem to have a lot of design elements, and I'm working it in as many different ways as I possibly can. I have about two-billion postcards. So until I use them all up, I can't stop. We'll see.

(Flo barking restlessly)

Jo Reed: Well, thank you so much.

(Flo barks)

Jo Reed: She's young.

Jo Reed: That's painter, video artist, photographer, and dog lover, William Wegman. Wegman had received two NEA fellowships: one in 1975 for video and another in 1982 for photography. If you go to Arts.Gov and click on NEA Arts and you'll find the magazine has devoted a special issue to artists who received NEA fellowships at pivotal moments in their careers. And you'll see an online slide show of William Wegman's work.

You've been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor. Excerpt from "Foreric: piano study" from the album Metascapes, composed and performed by Todd Barton, used courtesy of Valley Productions.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. And now you subscribe to Art Works at iTunes U -- just click on the iTunes link on our podcast page. Next week, novelist, Dean Bakopoulos

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed.

You may know him as the guy who takes surreal pictures of his Weimaraners; but that's just one strand of William Wegman's long and varied career.