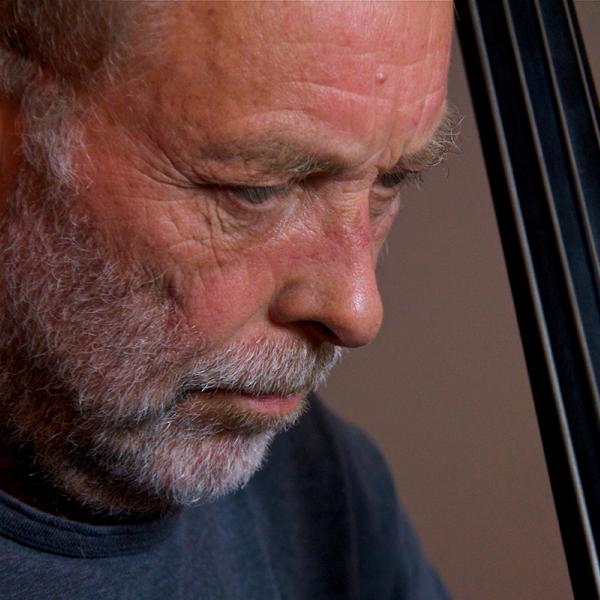

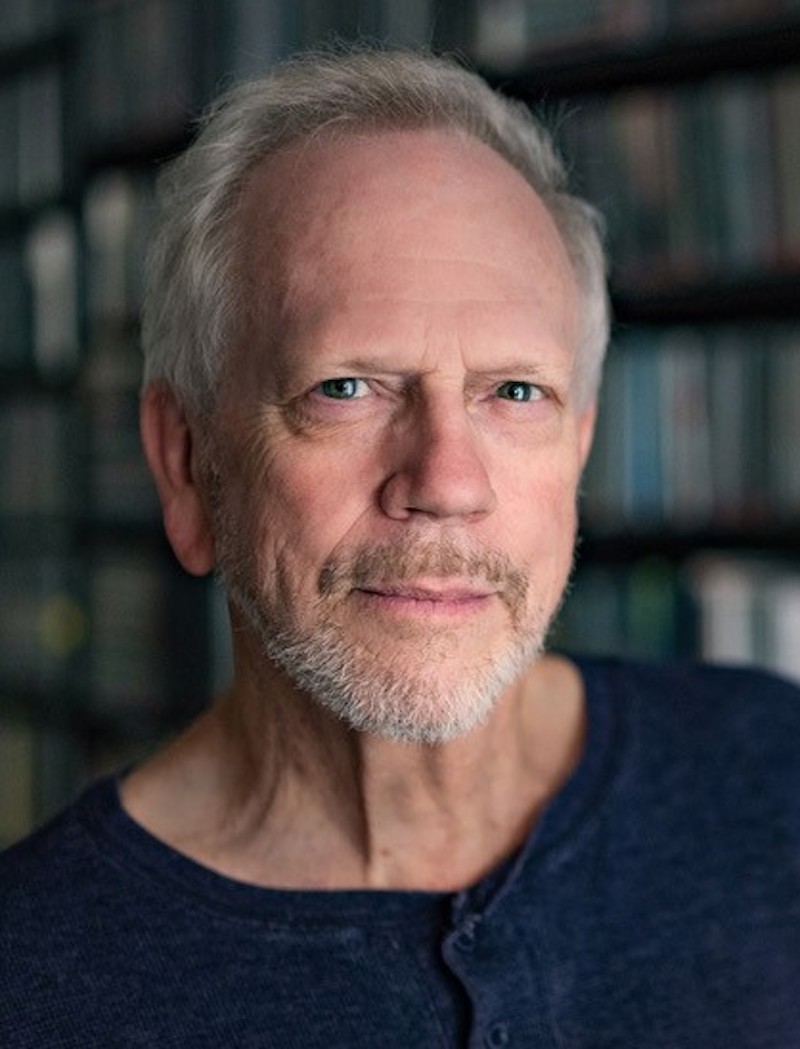

Nick Spitzer

Photo by Rudy Costanza, courtesy of Tulane University

Music Credit: “NY” composed and performed by Kosta T, from the cd Soul Sand, used courtesy of Free Music Archive

Jo Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, This is Art Works, I’m Josephine Reed.

Today a conversation with the 2023 Bess Lomax Hawes National Heritage Fellow Nick Spitzer. Folklife presenter, educator, and radio producer and host, Nick's journey is as diverse as the cultural tapestry he has spent his life exploring. Trained as a folklorist with an anthropological lens and marked by the rhythms of radio, Nick’s work blends sounds, stories, and cultural insights to create unique narratives that resonate with a wide and diverse audience.

With his early experiences in radio, and his groundbreaking fieldwork in Louisiana, Nick’s deep-rooted passion for music and culture has guided his career in exploring and presenting vernacular or folk culture. For example, he launched the Louisiana Folklife Program, he curated programs for the Smithsonian’s American Folklife Festival, he spent seven seasons as artistic director of Folk Masters at Carnegie Hall and Wolf Trap, and created the American Roots Independence Day concerts on the National Mall. Nick would go on to create, produce and host the acclaimed radio show "American Routes," which for 25 years has been playing Cajun, Creole jazz, blues, gospel, country, Tejano, Latin and Caribbean music, roots rock, and soul along with insightful interviews with the artists. And from 1997 through 2014, Nick Spitzer was also the host of the National Heritage Fellowship Concert—which is how I met him. So in many ways, interviewing Nick was like having a conversation with an old friend—one who still has the ability to surprise.

Jo Reed: Nick Spitzer, 2023 National Heritage Fellow. I've known you for years, and in preparing for this interview, I was shocked at how much I didn't know about what you do. So how do you describe your own work?

Nick Spitzer: Well, I'm trained as a folklorist from an anthropological point of view, but I also grew up through radio ever since college days, and I've continued to do radio. I see the sound recordings of people's personal narratives and conversations about culture as part of the way we exchange understanding of cultural difference and similarities, and a way to take deep understandings of culture, and with the addition of music and various environmental sounds and conversation, reach a really wide and diverse audience. So you could say I'm a public scholar, an engaged scholar, a public folklorist. I guess I'm a lot of different things, but most of the time I just see myself as somebody having a cultural conversation with somebody about the past and cultural continuity into the present, and what the possibility is for the future of culture's traditions in a creative sense and in a sense of maintaining continuities from the past to the future.

Jo Reed: Nick, where were you born and raised?

Nick Spitzer: Well, I was born in New York City in 1950, right at the middle of the so-called American century. I lived there until I was about three and a half, and then we moved out onto Long Island for a few years. But I really grew up formatively in a small town in Connecticut called Old Lime on the Connecticut River. And my mother, who was the single daughter of a suffragette always had a very strong sense of public culture and learning who people were around you and respecting them and so she made it clear to me all the time that, enjoy and watch, but don't say things unless you know what you're doingand I credit my mother introducing me to people and never being afraid to ask questions and just in goodwill try to build conversations. So that had a lot of impact on me as life went on and I grew up in this small town, Old Lyme. I just got a very strong sense of the totality of the town and learning to respect all the different people in the town and I just feel extremely lucky that I had that experience.

Jo Reed: Where was radio in your life when you were a kid?

Nick Spitzer: I grew up just as we were beginning to get FM stereo on the radio and my brother is four years older than I and when we shared a bedroom, I'd be hearing Little Richard and Chuck Berry and Fats Domino, “I found my thrill on Blueberry Hill,” and I'm thinking, what thrill, what hill? What is it? Dion's there singing away with Doo-Wop and anyway, so listening to my brother's music, I liked that. But when we got FM stereo, all of a sudden, here's Bob Dylan. Here's the Beatles. Here's all the new music that's coming out. It’s 1965 and everything is going forward in a new way and so for me, radio was magic. So, by the time I left to go off to college in Philadelphia, I was already very attuned to what I loved on the radio, whether it was a hockey game from Montreal in French, a baseball game from out west or all these wild and crazy DJs and just especially the music. I just felt they were playing these songs just for me and so I felt very good about radio for a long time and I never stopped loving it and then I started actually producing it when I was in college at WXPN, the college radio station.

Jo Reed: Before we go there, because I definitely do want to go there, you went away to college. You went to the University of Pennsylvania. Did you even know there was a thing called Folkloric Studies when you went there?

Nick Spitzer: No, I didn't. At Penn, I was listening to my mother and father. My brother had been an environmental kind of wunderkind at the age of 14. He was being interviewed by the congressional panels on why ospreys were dying in the Connecticut River Valley and I was much more into art and culture side of life and so I started to, I guess, find my way. They wanted me in the Wharton School because they said, “Well, he's going to be in ecology and we need someone in this family who will have a real business.” Ecology wasn't seen as a science at that point. My dad was a scientist. So my mother was very tolerant of what she would call my creative side, and said, “Now, Nick, Wallace Stevens and also Charles Ives and I know you like Charles Ives and Wallace Stevens poetry you've been reading in school. Both of these men became insurance workers. They were businessmen and then once they'd made a decent living, then they did their work, poetry and music.” She said, “You should be like that. You should go to the Wharton School at Penn,” and my father said, “You better go to the Wharton School.” But within one semester, I realized I didn't want to be an insurance person. I didn't want to be a business person. I didn't want to be a lawyer or a doctor. I wanted to just have the freedom to enjoy the music that was now coming to me through the college radio station and also going out and hearing Coltrane's old band in Philly and hearing Doc Watson play on campus and Mississippi John Hurt and I was just being open to this whole wide range of music and it did turn out that Penn had a very well-respected folklore and folklife department and so I started taking courses there and in anthropology and one of my key mentors was John Zwide, who actually ended up being the person that nominated me for the Heritage Awards. He's still alive.

Jo Reed: When or how did you connect your studies in folklife culture to the music you were playing at the radio station.

Nick Spitzer: I just opened up to the idea that avant-garde jazz could be understood as vernacular, like folkloric music and at the radio station, there's 20,000 records, this is the LP days and that wall of records was the sounds of people, their rituals, their festivals, their music. Their narratives and I stumbled onto two records in particular filed in the Caribbean bin that I said, “Well, this should be not in Caribbean because they're in Louisiana,” and there were two important records to me. One was the Ardoin family, Bois Sec, Ardoin, Alphonse Bois Sec, “Dry Wood” Ardoin accordionist, and Canray Fontenot, the fiddler and the other was Clifton Chenier, the big beat rhythm and blues Zydeco man and I said, “This music can't be in North America. This sounds Caribbean. That's why someone filed it here.” And so that set me on a course of how much more diverse is America than I've been taught and I began to realize it's much more diverse, not just the culture areas, but urban ethnicities and migrations and all these things are flowing through my mind.

Jo Reed: When you graduated from college you got a job in radio. How did that happen?

Nick Spitzer: So there's not much you can do with a B.A. in anthropology right off the bat. But I could do radio. So I ended up at WMMR Philadelphia. It was a Metro Media FM that was doing stereo roots, rock, pop, very eclectic and I was the afternoon guy and I did it for two years until I began to realize this just wasn't for me for eternity. But I did get to interview members of the Grateful Dead and the Kinks and Bette Midler and just lots of different people, because when the artists would wake up after their gigs, they didn't want to do anything live on the radio till one or two in the afternoon. So I'd always get the interviews and I got used to interviewing people live. I was under some pressure to play all these British hair bands and I'd say, “Why am I going to play Foghead when I could play Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters? Why don't I play some modernist jazz and make that work with Randy Newman and then go to Ray Charles?” We were told we were given complete freedom, but I was increasingly under pressure to play the latest pop acts and I just thought it was sleazy and I also just didn't want to stay and keep doing, even though was hip and a million hipsters would have loved my job, I just wanted to go deeper and wider.

Jo Reed: Deeper and wider---How did you go about that? What did you do?

Nick Spitzer: So I left there and I went on what I call my Jack Kerouac meets Woody Guthrie trip and went down through Virginia and I went to the Carter Family fold and I went to see Doc Watson at his house and I started doing interviews with people as I went and finally got down to the Gulf Coast and came along through Florida and Alabama. New Orleans for a day and I landed in Lafayette where I knew somebody and that that really set me on coming back to French Louisiana after that. But then I went to Austin, decided I would go to graduate school at UT Austin in anthropology and folklore. and I came back to Connecticut and basically packed up and moved to Austin and that's when I started grad school. And in Austin I did radio. I worked on what people called a hippie country station and I was the only non-Texan and they did make some fun of me, but I knew a lot of music they didn't know. Old Carter family and classic old country, certain types of blues. But they knew all the classic Texas stuff and I had to learn how much I liked Ray Price and Waylon and Willie and the Armadillo was going strong, the club there that became famous and since I was on Saturday nights because all the locals wanted to go out and party and I'd been working in grad school all week, to me, nothing was more fun than being up there with a friend or two and playing the music. Come midnight, the Armadillo closed. Who comes in the door? Willie, Waylon, Commander Cody, and I got to know those guys.

Jo Reed: Willie Nelson.

Nick Spitzer: Yeah, Willie Nelson. So I integrated myself into that world. But then the kind of new world of public folklore, my great hero was Archie Green, a labor folklorist and he and I started producing features for NPR. I did one on Folk Festival USA on Cajun and Zydeco. I did a 90 minute documentary and I told all the people I was starting to meet, both Afro-French and Cajun, “This is going to be on,” and they got a huge response and I began to think, well, I can just use radio to reach all these people and support them in a public place and they don't have to go to the same bingo parlor or the same dance hall.. They can just all hear themselves, they'll be together on the medium.

Jo Reed: Because you went to Louisiana for fieldwork with Afro-French Creole music and that was really pivotal and I'd love to have you talk about that because that really opened up the music of Louisiana that's been central to your career.

Nick Spitzer: Well, it also opened up the idea that cultures aren't static, that cultures change and that there are cultures we don't even understand fully because the Afro-French people were neither fully French. They were not white Cajuns. They were not white colonial descendants, but they were somewhat separated from Black folks too. They were not Black Americans. They were Afro-French people and they used the term Creole and their music was a mix of French sources from West Africa and the Caribbean rhythmically, sonically in various ways and American blues. So I began to see that the lines between people and culture were not as static as I've been brought up to believe and one of my key teachers was Americo Paredes who I'd never known before. I was in grad school, but he was a border scholar, also a singer and he worked on the Texas-Mexican border and dealt with the culture that was neither fully Texas nor fully Mexican, but a place where a lot of different culture, music flourished and was very creative.

Jo Reed: Okay-- you went back to Louisiana, to Lafayette—how did you connect with Alphonse Bois Sec Ardoin

By then I was starting to go all the time to little correo de Mardi Gras, Mardi Gras runs and all these little dance halls and I had met a Bois Sec Ardoin at Mariposa. I went to this festival up in Canada, near Toronto. Alphonse Ardoin was there with his son. I talked to him after his set and I didn't speak any French. I had only studied Spanish, but he said to me something I never forgot. He said, "Quand tu visites la Louisiane, visite nous à la maison." When you come to Louisiana, come see us at the house and so when I got to Lafayette, I told that to a couple of friends and then they sent me, said, “Well, go see Dewey Ball for the Cajun fiddler,” who, like Bois Sec, would become a National Heritage Fellow in the early 80s. and Dewey let me live at his house. I lived out back in his outdoor kitchen and for breakfast and dinner and a place to sleep, I fed his cattle. I made sure the electrical fence was working. I harvested corn. I delivered insurance checks. He had a little insurance business. I helped him move furniture. He had a furniture store and one night, I came home and I said, “Dewey, I saw a sign that said the Ardoin family, Quatre Coins, ce soir, Four Corners Club tonight and he said, “Oh, Nick, you got to go there and see them. They're the best.” So I go there and there's Bois Sec, the man who told me, come see us at the house and by now I'd been learning pretty good. I had Louisiana French going. So I walked up to him and I said, "Monsieur Arduin, est-ce que tu te rappelles de moi? Moi, je suis un experte, on a rencontré longtemps passé." And he says to me, "Moi, je t'ai dit visite à la maison quand tu visites la Louisiane." I said, “Exactement, that's right. Come to my house,” and so he said, “Tomorrow, at my son's club, we'll have an afternoon fais do-do. You should come to that.” So I went, it was about 15 miles from where I was staying and I went there mid-afternoon and I went to this little club. I never looked back. I eventually moved there and rented houses there and eventually I would live in the Ardoin house for three months It was like the deal with Dewey except I was gardening and I was going to the store. I would always be there for family dinner. I shared a room with the youngest son who was a couple years younger than me. I really lived the life. I lived the life under a very strong matriarch of the family. Madame Ardoin took no guff from her husband or any of her guests.

Jo Reed: Let me just interrupt for a second. But in the meantime, you were able to record them and interview them and hear their music.

Nick Spitzer: Oh, yeah. I interviewed them and actually I got a grant from the NEA and I made sound recordings of the Ardoin family and many others. I recorded old Creole songs, old French songs and I did two albums. One called Zodico, Louisiana Creole music. That was a wide range of urban, rural, more French, more Afro and I'm in the process of getting all this stuff out. I never brought it out as CDs and then I did another one with the Lawtell Playboys. So I did those and I started doing more radio and once my grant ran out, I was substitute teaching in schools which was another way, great way to learn what's going on culturally somewhere. So on and off for a year and a half, I was there for months at a time. Go back to Austin to handle some formality or do something related to my graduate work. But basically I just lived it and loved it.

Jo Reed: You ended up doing work for the Smithsonian for the 1976 Bicentennial. What did you do for them?

Nick Spitzer: Well, I went to Washington as a presenter of Louisiana French and Creole. But also old-time country and blues and all the things that I knew something about and that's where I met Bess Lomax Hawes. Bess was the deputy director of the Office of Folklife Programs and she was very good friends with Joe Wilson, who ran this nonprofit National Council For Traditional Arts and Joe introduced me to Bess. Bess was extremely excited that I had learned Louisiana French and had background in folklore training and wanted to do public work and was at the festival and was learning how to be on a stage and introduce people and do interviews and translate for publics and stuff. So after that happened, she said, “We really want a state folklore program in Louisiana. If we post a listing, I hope that you will apply for that,” and I said, “Why wouldn't I?” So I finished all my coursework and the listing came up and I applied and she was close to Al Head, the director, he met me and we got along very well and so he hired me to be the state folklorist. So now I've moved from making recordings and public radio and doing the scholarly stuff towards a dissertation to suddenly being a Louisiana state official, if we could call me that. And I had pretty much free rein to lobby and I got pretty effective at it to where they started giving us money to do grants and projects and in that time we did a state recording series, blues, old time country, Cajun, Zydeco. We did a state guidebook, “Louisiana Folk Life Guide to The State”, like the WPA guides of the ‘30s, but focused on living traditional arts and culture and then the biggie, the World's Fair, Louisiana World Exposition. Russell Long and Carolyn Long got us a million dollars from the timber industry to run a pavilion in an old warehouse, a tobacco warehouse down in New Orleans and so we put a crew together and for six months by hook and crook, we ran a stage, a little nightclub inside this place called The Back Door by then I'd gotten an exhibit together called the “Creole State” and we had every Louisiana traditional artist we could find, the craftspeople, boatmakers, weavers, spinners, older ladies that sing cantiques, Cajun, Zydeco, Native American. And within a month, we got a tremendous review in Newsweek, a full page review in Newsweek as the best thing at the World's Fair.

Jo Reed: Congratulations! So tell me, first of all, how long were you in the position of folklorist in Louisiana?

Nick Spitzer: Seven years.

Jo Reed: You moved to the Smithsonian, curating programs for the American FolkLife Festival—what goes into that work

Nick Spitzer: Well, the first one I did at the Smithsonian was before I was hired to be there. I did the Louisiana state program. What goes into that is doing a lot of field work, but because I've been doing the World's Fair programming and helping a great team of folks there and working all around the state, I already had a easily to find 120 people that we knew could go to Washington whether they were old time lace makers, fiddlers, French folk, African-American, Vietnamese, all the different people in the state, lots of Native Americans. We knew who would be willing and able to be out there for two weeks on the National Mall. I had had some experience before that where I'd come in and helped, so I understood what the festival was more or less about and so that year, the two featured areas were the state of India, the country of India and Louisiana, and they seem to go pretty well together. There are both very strong differences of color and religion and magical rituals and festivals and music and it was a festival to remember and it was through that really time that it was cinched that I would come up there and so in the October of ‘78, I moved to Washington. I enjoyed my time at the Smithsonian and I did five years as a federal and then I decided not to stay and continue. But I said, I'll be an adjunct and so I became a research associate and then's when I really became independent.

Jo Reed: What was some of the work were you doing as an independent presenter

Nick Spitzer: I started doing tours to the Seychelles Islands with Louisiana Creoles, Zydeco people out in the Afro French islands and the Indian Ocean and the most important thing for me was I did the Centennial of Carnegie hall with a series called Folk Masters and that was got me going with, how do you do traditional arts on proscenium stage with all the attendant stylistics of Carnegie Hall and that in turn led me to actually after that first year, just to come to Wolf Trap and do it there the next six seasons. And then in the middle of all this, from 1990 to 1997, we did the American Roots R-O-O-T-S Independence Day concert and I got it out live on NPR around the country, all stations that wanted to carry it and we could see 250,000 people from there, their bodies in front of us and I brought up Rebirth Brass and all these great New Orleans people that I knew and we had great Cajun music and Zydeco and traditional fiddling and over the years we had Carl Perkins and we had the Staples Singers and we had all manner of gospel. And the evening events from six to nine when the fireworks would start. Those were when we really laid it out and I co-hosted it with Fiona Ritchie and Georges Collinet and a lot of different people. But so suddenly this idea of concertizing on a big stage was outside a festival and then it was out on public radio and the Park Service just helped us at every turn. After doing that for all those years, I went to Santa Fe for two years to a think tank and then I said, “I'm going back to Louisiana. I miss that.”

Jo Reed: What led you back to Louisiana, Nick?

Nick Spitzer: Well, I said to myself, where is home in my life today? And I can't go back to Old Lyme, Connecticut. I'd left all that. I love Philadelphia, but I'm not a college kid anymore. I had moved to Louisiana twice. I'd gone in to do my field work there. Then I worked for the state. And I said to myself, I will move to New Orleans where I always had loved it and New Orleans is a Creole city, deal with people called Creoles with a mixing and the mingling of Sicilian, French, African-American, Afro-Creole, it's a global city almost of the 19th century and through the Park Service, I had become friends with people at the University of New Orleans and they hired me as a folklorist there and I taught cultures of the Gulf South. I taught oral history. I taught Creolization cultures and Creoles and cultural Creolization and I did that through Katrina.

Jo Reed: You mentioned Creolization and the concept is pretty central to your work—say more about what you mean by it and how it drives your work

Nick Spitzer: So you could argue that on one level, there's people called Creoles with a capital C here and other places in the Caribbean and parts of South America. But moreover, you could look at things that are Creolized and mixed and mingled. So from my point of view, the world is in Creolization. We're in constant contact where continuities of old culture are mingled with new creativities and new things emerge. The easiest example is Ray Charles. Ray Charles grew up, going with his mom to church and he also went to the j uke joint where he learned how to play blues piano with Wiley Pittman. He mingled the blues, the lonesome sound, the piano playing with the gospel shouts for joy and he ends up with a new music. We call it soul and so to me, soul didn't exist before. There was gospel over here and there was blues over there. So he made soul out of sacred and secular music around him and that's why we call him a genius. He wouldn't call himself a Creole, he'd call himself a Black American, but the music is a mix that represents something new based on the merging of traditions. So I'm really into that in American society, a creative society where we have to look at the future as much as the past and creativity from the past will lead us to more creative things in the future. So I see the world in Creolization and I don't look for the barriers between groups of people. I look for what they've done together.

Jo Reed: And you created your radio show American Routes when you moved to New Orleans—I want that origin story

Nick Spitzer: Well, I also said to myself, if I go back, I'm going to start a new radio show and I can more efficiently reach more people if I do a post-produced show, not a live event and so I decided it would be called American Routes, R-O-U-T-E-S and in ‘97 is when I moved back and the university gave me financial support and allowed me to apply for grants and I was very dutiful. I wrote the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and said, "Look, we'll do all the background research on this to show you why we think it'll work." Because I was very wonky. They wanted all that information and they said, “Just send us a demo.” So I created a half hour demo. We sent it in and a week later, the head of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting called me and said, “We're going to fund this. We want you to do this for at least a year. Just do what you're doing. Everyone thinks the demo is fantastic. It's what America needs to hear,” and I said, “That's what I think too,” and so we started on the air in April of 1998 with seven stations. Little by little, within about a month, we had 30 stations. By the end of the year, we had 60. A coffee company was underwriting us in Louisiana and life just went on producing the show out of an old bottling plant, water bottling plant in the French quarter and it just continued for 25 years to the current moment and in that time, we now have 385 stations. We had continuous support from the NEA and the NEH and local businesses and we made it to 25 years and just has continued to grow. We're one of the very few cultural performance programs left in public radio. We're the only thing on the air between Austin and Chapel Hill, North Carolina that could be understood as cultural programming, going to the national network and TV or radio and it's just been slow and steady. Keep going, keep going.

Jo Reed: I know you received offers from television but you always stayed with radio. Why?

Nick Spitzer: I just felt radio is better for me because the microphone disappears. It's just your voice, somebody else's voice. We can record a live event. We don't need the lights everywhere. We can just have a conversation and people get comfortable and they go deep with their hopes, their joys, their sorrows, the why and what and how they make the music or do the craft they do. I just began to see the world more interconnected, more creolized and more capable of having the kind of eclectic program that argues for what Americans share, like country music and blues and jazz and gospel music and then what distinguishes regions.

Jo Reed: For people who are unfamiliar with American Routes, how would you describe the format

Nick Spitzer: These days I refer to American Routes format as a Gulf South by Southwest with sojourns to the Caribbean and all points across the country. I feel like in New Orleans, there's a lot of pride that we're inclusive of something as eclectic as what we do. Something that many program directors said, “Oh, you can't do something when it's mixed like that.” Well, we've done it and we keep doing it and we're not the biggest show. We're not a news show, but we kind of commingled information in a newsy kind of way with culture and performance What we try to do is find concordances in words, in mood in sonic things, contrasts and continuities that we can do segues, which is sort of the art form of radio flow of sound and maybe every third sound, every third song will be very familiar to somebody, but it might be a familiar artist with a song they've never heard him sing or a song that is quite familiar by a familiar artist, but not the one they might've expected to hear it sung by and so you're always messing with things that work together. You can play old time string band music and make it work with New Orleans traditional jazz. You can play blues and gospel and make it work with Klezmer. You can play country and make it work with Hawaiian. You can do all kinds of things based on the sonics, the semantics, the moods for the segues. That’s one thing we're proud of, that while we can narrate who the artists are and where they sang and a bit about the biography and the culture, we want people just to enjoy the show whether they're listening in the foreground or the background and so the eclecticism is not a barrier. It's an invitation.

Jo Reed: You’ve also, in the midst of everything, been teaching at Tulane now, first the University of New Orleans and now Tulane for many, many years. I wonder how teaching and radio come together for you. Somehow it just seems to me being around students and younger people has to be good for what you bring to American Routes.

Nick Spitzer: Well, , we have probably a half a million to three quarter million listeners each week, depending on the season and the show and whatever. I go to a classroom, I have anywhere from 10 to 40 people. I've done a couple of bigger classes, but in a funny way for me personally, radio is a lot easier to do. It's all post-produced, you can always do a pickup on a fix. I'm working with an engineer and co-producers and interviewing artists and trimming the interviews and mixing music. It's a team effort and when it's made into its one hour and 59 minute iteration for being sent out, I just feel great and I hear it on the radio. But I've done radio for so long and it's so common to me to do that. I don't feel pressured by doing it. I love the interviews and everything. But when I'm in a classroom I'm always trying to figure out how to reach students. It's very challenging, exhausting in some ways. At Tulane, more of the students are not from Louisiana though that's beginning to change. Now it's gotten to where there's more and more younger people who are hip to deep roots and especially blues and gospel and the sources of rap and hip hop and certain Black genres that are classic forms of Jubilee and this and that, and a lot more Cajuns and Creole descendants and so they're really excited to hear how the old music ends up as French rhythm and blues. They go along for the Creolization ride and discussion and enjoy it. But it is a lot to try to emote and intellectually work with audiences of students versus something where I've been knowing what I wanted to play and scripted and ready to go with the team. It's sort of an interesting balance between the worlds but it does take a lot of energy on both ends.

Jo Reed: You were also the host for many years for the National Heritage Fellowship Concert and I wonder first what your memories are of that experience, but then having been in DC as the recipient of the award.

Nick Spitzer: It was weird. The first ones Heritage were 1982 and who's getting the awards? My teachers in Louisiana, Bois Sec Ardoin, Canray Fontenot, Dewey Balfour, all these people, I wasn't the host then. Pete Seeger was hosting and there were many, many other hosts over the years. I see the people in the families where I lived as as much my teachers of folk and traditional arts and how to make policy and how to produce programs as anybody in the Academy that I learned from, more so. Those people were like my new family, a lot of them, especially in the Creole communities. But it was a huge moment for me to start going on stage in ’97 when the last host retired, they asked me to do it. And from ‘97 to 2014, I did it. It was a lot of fun to go on stage and improv with people and help them get comfortable for that moment and some of them were very shy and quiet but we always found ways to enjoy one another's company I tried to give them two or three days of fun, humor, what we could talk about and so I just loved these shows. They were just like group improvisation with a Ukrainian egg decorator, a shy older lady that did quilts in North Mississippi, people that you've never heard of, but also some of the greats of the culture, of cultures that we knew like B.B. King, and people that I'd always loved, all kinds of different blues people, Zydeco man, Boozoo Chavis, his family, just all manner of people, some of whom I'd already known well, but most of whom I'd never met before.

Jo Reed: But I also have to ask, the fact that you're given the Bess Lomax Hawes award has to be particularly gratifying because I know she was such an influence on your work.

Nick Spitzer: Oh, definitely. There's a picture of myself and Bess that somebody took at the 1985 Smithsonian Festival. We were in the Louisiana area and we're both kind of smiling and talking and I remember how much she influenced me and made me feel that I could be a state official, that I could manage not just working in Louisiana, but that maybe one time I'd come to Washington eventually, that really everything I could do to better understand and present culture could flow from the work. and I saw her as kind of a matriarchal grandmotherly blessing figure in my life and so then it was named after her-- yes. It was very meaningful to me for it to happen that way.

Jo Reed: I could not be happier, Nick, that is the truth. So many, many congratulations on a well-deserved award and many years ahead for “American Routes” I think that is a great place to leave it, Nick. Thank you for giving me your time.

Nick Spitzer: Yeah, thank you for asking me the questions.

Jo Reed: That was folklife presenter, educator, the producer and host of American Routes and the 2023 Bess Lomax Hawes National Heritage Fellow Nick Spitzer. To find out more about American Routes, check out its website, American Routes.wwno.org. And you can check out all of the 2023 National Heritage Fellows on our website at arts.gov. We’ll have links to both in our show notes.

You’ve been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on Apple. It helps other people who love the arts to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

In this podcast, folklife presenter, educator, radio producer, and 2023 National Heritage Fellow Nick Spitzer discusses his multifaceted career, his upbringing, and his understanding of cultural innovation in America. We talk about his lifelong passion for radio and his discovery and embrace of American vernacular culture, as well as his career as folklorist in academia, government, and media, including his NPR and Smithsonian collaborations and American Routes, Spitzer’s renowned radio program which blends music from many different traditions with cultural storytelling. Spitzer discusses his fieldwork in Louisiana and experiences with Afro-French Creole music; his understanding of cultural dynamism; and his journey through different American regions, absorbing and understanding not just the diversity but the dynamic and innovative interactions among American cultures. He also reflected upon the significance of receiving the Bess Lomax Hawes National Heritage Fellowship, the privilege and responsibility of working in American vernacular culture, and the future of American Routes and Spitzer’s commitment to its continued contributions to cultural understanding.

We’d love to know your thoughts--email us at artworkspod@arts.gov. And follow us on Apple Podcasts!