The House That Ted Built

Chanel DeSilva of the Trey McIntyre Project at Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival in 2014. Photo by Christopher Duggan

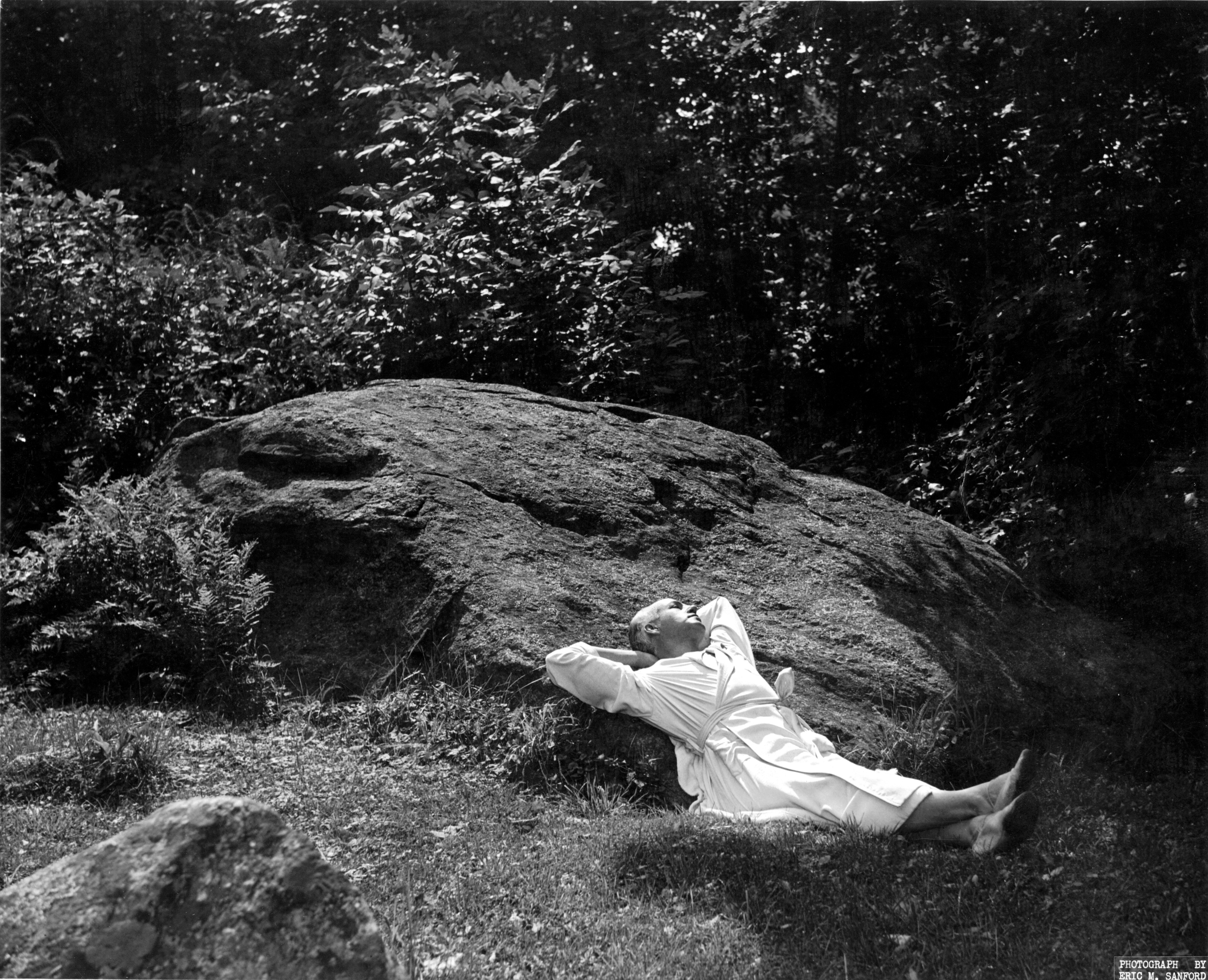

In the same way that a picture can be worth a thousand words, a short film can tell a decades-long story. Made in 1937, Kinetic Molpai opens on a weathered New England barn. A man—modern dance pioneer Ted Shawn—enters the frame, bare-chested with eyes cast forcefully to the horizon. He moves in a simple but muscular way, eventually calling on an ensemble of six men, who make up Shawn’s company, the Men Dancers. They begin a dance inspired by ancient Greek ceremonies and choreographed by Shawn. The short performance was filmed at Shawn’s farm, Jacob’s Pillow, in the Berkshire Hills of Becket, Massachusetts.

That farm, which dates back to around 1790, has since become the renowned and much-loved summer dance haven, Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, a place where dance is created, performed, taught, and preserved. Since 1969, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has supported its work for a cumulative total of $4.2 million, and the organization was awarded a National Medal of Arts in 2013.

Today, Kinetic Molpai is woven into the history of Jacob’s Pillow. Taken together, film, festival, and the NEA tell the story of a truly American enterprise, one that seeks to encourage creativity, support the development of new work, document and preserve this ephemeral art form, and encourage a passion for dance among both local and international audiences.

|

From Farm To Festival

In Jacob Pillow’s early years, 1933 to 1939, Shawn and his Men Dancers gave lecture-demonstrations for local residents when the company was not on tour. This was during the Great Depression, and Shawn wanted to demonstrate that dance could be a legitimate career for American men. At an admission fee of 75 cents, Shawn would speak to those assembled, offer a demonstration, and then present a selection of ensemble and solo dances. There was seating for 25 people for that first “tea,” as Shawn called the event. Fifty-seven people showed up.

In 1942, a theater with seating for 514 was erected, the first facility in the United States built specifically for dance. The Ted Shawn Theatre is still the festival’s main stage. The programs that Shawn presented there were diverse, typically including a headliner such as England’s prima ballerina Alicia Markova and her partner Anton Dolin, followed by a modern piece, and then a traditional or “ethnic” dance, as it was described at that time.

This presentational approach had the benefits of attracting an audience interested in seeing star performers while expanding their imaginations for what dance could be. Jacob Pillow’s Executive and Artistic Director Ella Baff said, “I think Shawn’s mixed-bill approach helped audiences build awareness and ‘muscle’ for the form.” (On the day of our interview, the Pillow announced that after 17 years, Baff would be stepping down to take a position at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.)

Diversity remains a hallmark of Jacob’s Pillow performance programming. The first year the festival received an NEA grant, 1969, artists included Maria Alba’s Spanish Dance Company, American Ballet Theatre (ABT), Gruppe Motion Berlin, and Arthur Hall’s Afro-American Dance Company, among others. In the 2015 season, also supported by the NEA, one could see Nederlands Dans Theater 2 from The Hague, Netherlands; the world premiere of ABT dancer Daniil Simkin’s Intensio; and Dorrance Dance with tap star Michelle Dorrance and folk/blues composer Toshi Reagon leading her band BIGLovely.

Baff explains that building an adventurous audience for dance has a lot to do with “dispelling preconceptions, welcoming the public, and guiding them to appreciate that, like all art forms, dance has many possibilities within it. Many people find an immediate personal connection to dance, and many find it difficult to approach or are simply newcomers. And we’re here to help them all love it.”

With 50 companies, 160 performances, and 200 free events offered over the ten-week Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, there’s a lot of dance to love.

|

Save And Share

The archives of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival are housed in Blake’s Barn, part of the original 1790 farm. The two public spaces in Blake’s Barn are a gallery that displays items from the collection, and a new, adjoining reading room featuring book stacks, a large screen, and seven computer stations for students, researchers, and visiting artists to use.

Below the library, the archives are housed in climate-controlled rooms. Floor-to-ceiling shelves storing videotapes, film reels, and archival boxes of photos share space with steamer trunks from the early years of the 20th century, some storing costumes of long-ago dances.

Norton Owen is the Pillow’s director of preservation, and has been with the organization in various capacities since 1976. He notes that appreciating the value of documenting and preserving dance was “baked into the Pillow from the beginning with Shawn.”

“Shawn always said, ‘Dance is the only art form of which we ourselves are the stuff,’” said Owen. As Shawn understood it, dance was not only something beautiful to be admired, or an evening’s entertainment, but also had a rich history and was worthy of study and scholarship.

In 1986, while managing the School at Jacob’s Pillow, Owen put in an application to the NEA’s funding category Dance/Film/Video to continue building that rich history. His request was to support the transfer of footage of Shawn’s Men Dancers from the deteriorating nitrate film stock to videotape, and to reunite the silent film with newly recorded scores by the Men Dancers’ original composer/accompanist Jess Meeker. The Pillow received a $12,000 grant.

Other preservation projects ensued. Then in 1993, the Pillow landed an NEA Challenge grant of $556,000 for its Dance Anthology Project. The Challenge program provided large grants, or as the NEA noted in its annual report, “venture capital,” to support ambitious new programs.

The Dance Anthology Project, which went on for several years, had three components mirroring the Pillow’s three areas of activity: presentation, preservation, and education. The project’s revivals and new commissions were built around a central artistic work or dance tradition, such as Bill T. Jones’ Still/Here or the Cambodian Artists Project. Radiating from that central theme would be new work, educational opportunities, and documentation of the creative process. Owen observed, “What was wonderful about it was that it really did attempt to show how dance was made of all of these myriad efforts. What was part of Sam’s [Sam Miller, the Pillow’s then-executive director] brilliance was by getting all of this together, you begin to make a larger story,” in which each component “becomes ennobled” by its contribution to the whole.

Going Digital

With the arrival of a new century and growing possibilities of digital technology, the opportunities for dance preservation became numerous and exciting.

For Jacob’s Pillow, digital technology made its first major appearance in 2004 in the traveling exhibition, America’s Irreplaceable Dance Treasures: the First 100. The exhibition was conceived by the Dance Heritage Coalition, co-curated by Owen, and supported by a $150,000 NEA leadership initiative. The exhibition included a free-standing kiosk with a touch screen that allowed visitors to search a database of text, audio, and video clips. (Among those video clips was Kinetic Molpai.) The next development was a Jacob’s Pillow-centric kiosk funded through the NEA’s American Masterpieces initiative and unveiled during the Pillow’s 75th-anniversary season in 2007.

But as wonderful as it was to have digital materials available with a touch or a swipe, people began to ask, “Can I get this at home? Is this online?” The next step was to create an online platform to showcase these materials so anyone with an Internet connection could delve into the Pillow’s holdings. That platform became Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive, or JPDI, and was launched in 2011 with funding in subsequent years from the NEA.

JPDI 2.0 debuted in May of this year. With well over 200 video clips, the web section contains curated playlists and enhanced search capacities. A game called “Guess” tests users’ dance know-how by displaying randomly selected videos with multiple-choice questions. Owen noted that 30 to 40 videos are added to JPDI each year with an emphasis on filling artistic gaps so that the resource is as encyclopedic as possible.

|

From One Body To The Next

Presenting a wide array of live dance performances to audiences is important. Documenting and preserving those dances is important. But teaching the next generation of dancers is arguably the most important.

Training has always been a part of the Pillow experience. Shawn insisted, for both aesthetic and practical reasons, that part of the training regime for his Men Dancers was manual labor. On a practical level, Shawn’s ambitions for Jacob’s Pillow required development of the farm. So, in addition to hours in the studio, the men cleared land, built housing and studios, and repaired roads. But aesthetically, the shape, dynamics, power, and pride of physical labor were qualities that Shawn instilled in his choreography and wanted audiences to take away from his dances.

Today, that ethos remains via a robust internship program that supports all aspects of the festival while giving young professionals opportunities for hands-on experience in festival administration, production, and videography.

Another unique element of student life at the Pillow stems from its rural setting. Students and visiting artists live on campus in wood-frame houses, some of them built by Shawn’s dancers. For a young student from Oklahoma to rub elbows in the bookstore with dancers from Brazil, or to have lunch with an artist from Cambodia, can be as life-changing as what happens in a studio or theater.

Classes are arranged in a modular structure with two- or three-week sessions for ballet, contemporary dance, social dance, and musical theater dance. Immersion is a key concept with a rigorous schedule of classes, rehearsals, and weekly performances for festival audiences.

This summer, Camille A. Brown and E. Moncell Durden led the social dance module. Brown, a dancer, choreographer, and director, led students in an exploration of African-American dances from jazz to hip-hop. Brown said, “Teaching juba, the ringshout, and buzzard lope in the midst of ancestral ground [Jacob’s Pillow was a stop on the Underground Railroad] led us on a journey of unpacking, unearthing,

guiding, following, breathing, healing, understanding, self-reflection, and communal grooving.”

As In Art, In Life

Walking down the gravel pathways of the Jacob’s Pillow campus, going to an exhibition in Blake’s Barn, or a preshow talk with a visiting artist, or navigating around a gaggle of students on their way to a performance, the sense of history here is palpable. The innovation, strength, foresight, commitment to dance, and the utter American-ness evident in the Kinetic Molpai clip are very much a part of life here—

just as Shawn would have wanted it.