War Cuts

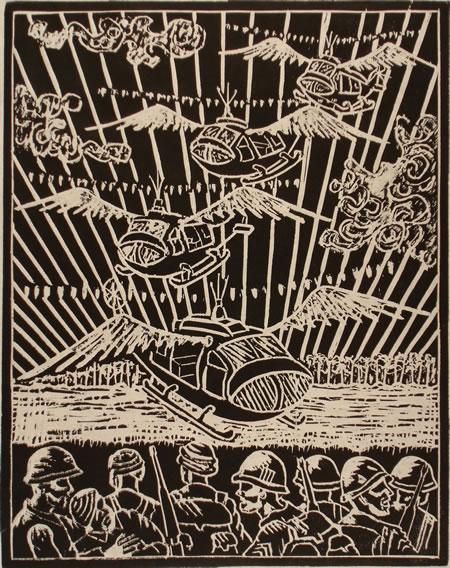

Extraction.

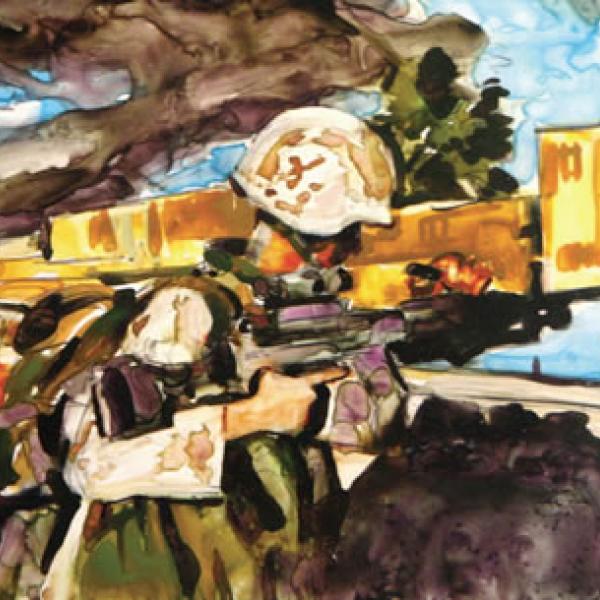

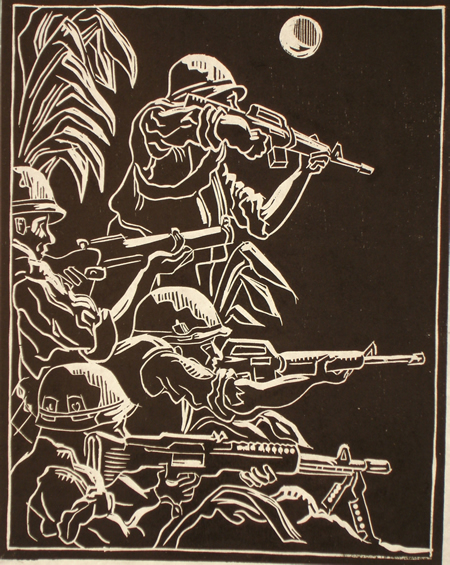

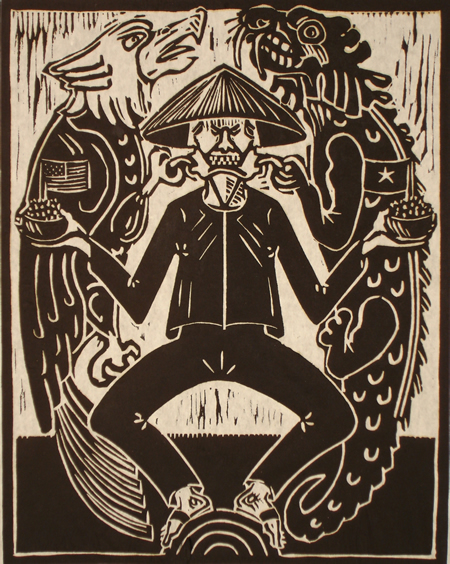

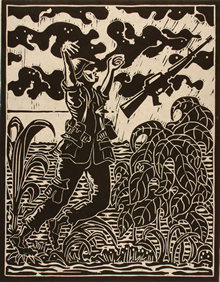

All images courtesy of Don R. Schol

Artist Don R. Schol dreamt about Vietnam for decades after his return. As a combat artist from October 1967 to April 1968 with the U.S. Army's Vietnam Combat Artists Program, he captured images and recorded experiences, turning them into works of art for the annals of military history. When Schol returned home from war, the public was so hostile towards veterans that he never spoke of those experiences in Vietnam that would haunt his dreams for years to come.

Forty years later, after a long career as an artist and academic, Schol finally found the courage to speak through Vietnam Remembrances -- a collection of 16 woodcut prints on rice paper based on his experiences in Vietnam. Vietnam Remembrances premiered in 2009 in Dallas, Texas, and later became the subject of his book, War Cuts, accompanied by Schol's reflections on the art and war, with a forward from Senator John Kerry.

The NEA sat down with Schol and his wife, artist Pam Burnley-Schol, in Argyle, Texas, to discuss art, war, and the process of healing. The following are excerpts from the conversation.

NEA: You were trained as an artist. Did you intend to go into the military?

DON R. SCHOL: No. I started out as a philosophy major at the University of Dallas, and then I met a sculptor there who had served in WWII on the German side. He was primarily a woodcarver from the great German tradition, and I became really interested in that. Consequently, the bulk of my professional career has been woodcarving.

I went on to get my MFA in sculpture from the University of Texas at Austin and was invited to teach at a prep school in Dallas after graduation. Then I received the draft notice.

NEA: How did you go from getting a draft notice to being a part of the Vietnam Combat Artists Program?

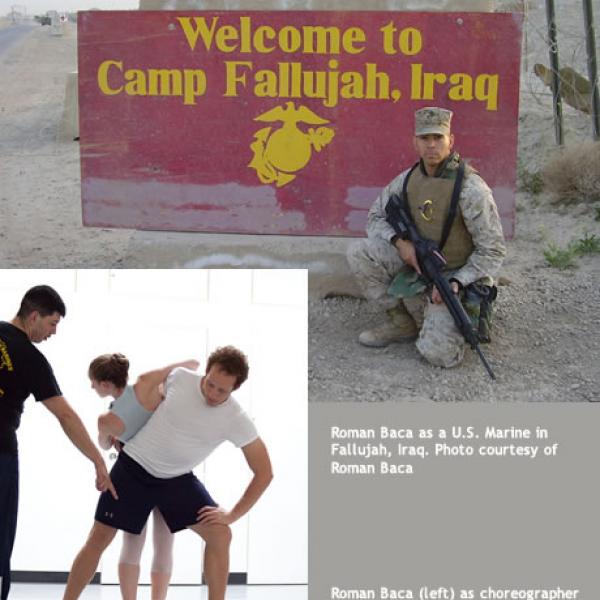

SCHOL: I had about a week to get things in order, and then I went through basic and advanced training in Fort Dicks, New Jersey. I was assigned to be a platoon leader, but I had heard about this artist program, so prior to leaving for Vietnam I sent a letter to Washington to express my interest.

I didn't even know I was in the program until I got to Vietnam and a captain took me to see the colonel who was administering it. Participants were required to be both professionally trained combat soldiers and artists, and I fit the bill.

NEA: What did you do as a combat artist?

SCHOL: During the course of Vietnam, there were a total of nine teams of five soldiers each, and I was leader of team five. My team traveled with a lot of photographers, but the Army specifically wanted artists' interpretations of the experience, so we carried cameras, sketchbooks, and journals when we went out on operations with units…we also carried M16s and worried about running into the VC [Viet Cong]. A lot of our work was based on the combination of our recorded experiences and images.

NEA: Were you expected to do bigger works of art or collections based on your experiences there?

SCHOL: Yes. Each team was in Vietnam for six months, and then we went to a studio in Hawaii, where we made bigger collections of art based on our sketches, notes, and photographs. I made ceramic and clay sculptures and a lot of drawings. All of our collections are now a part of the National Archives War collection, under the auspices of the Army Center for Military History.

|

NEA: You undoubtedly experienced terrible things in Vietnam. How did you process what you were seeing?

SCHOL: I think I was psychologically prepared, because my father was a POW in WWII, and he told me horrific stories. Actually, I think it affected me more after we returned home, because for 20 years or so I had dreams about it. I thought that was odd but never talked about the dreams to any other veterans for a very long time. None of us ever talked about being in the war…you just didn't do it because of how unpopular it was. My collection was created 40 years later.

NEA: Did your experiences in Vietnam change your perceptions as an artist?

SCHOL: For me, it changed my art in a general sense, and as my wife says, it's much more existential. I don't deal with frivolous things anymore. While there's still a lighter side to my work that's playful, I'm an expressionist.

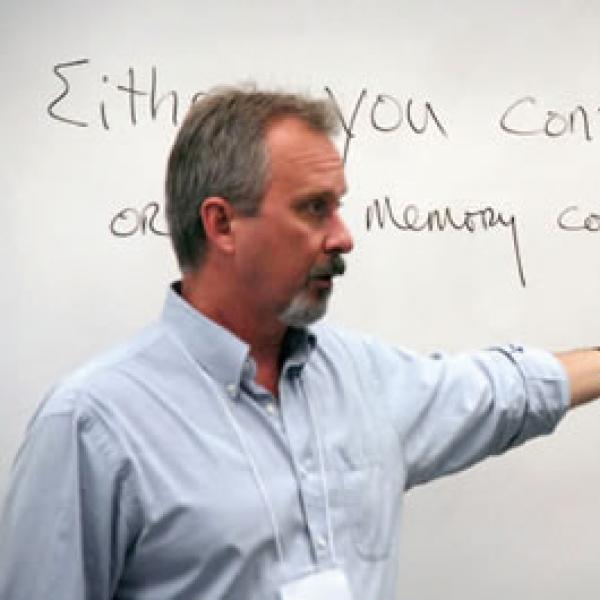

NEA: You taught at the University of North Texas for almost 40 years. Did your experiences in Vietnam also change how you interacted with the students?

SCHOL: Yes, it did. I dealt with young men who went to war and came back, and then young men who had not gone to war. Their perceptions were completely different, and I was able to handle that. Also, I saw the students differently, and I have a great deal more empathy for them. I guess I was changed person, so I felt like I was more patient.

NEA: Had you done any artwork about Vietnam before Vietnam Remembrances?

SCHOL: No, I hadn't. After all of those years, I finally decided to do it. I had put my experiences into perspective by then and could finally do this work, distill all of that was in my mind. It helped, too, that I started meeting with other veterans who had been having those dreams. They encouraged me to do the work.

NEA: How did you choose the medium of woodcut prints?

SCHOL: For a woodcarver, this just made sense and seemed like the natural thing to do. I would make a drawing first and then translate it into the wood. There was something magical that happened -- the bridging between the drawn line and the cut line. And then you run a proof and you're like, wow, I like that. It's still a strong image for me.

|

NEA: Did you start with a particular print and build from that, or did you already have clearly defined images for the collection?

SCHOL: I started with Either-Or. I wanted to explore Vietnam first and what that war was about. As you see in this, the Vietnamese people were tugged back and forth. The Americans were on one side, and the VC were on the other, and they were trying to decide from whom to take the bowl of rice. While the Americans provided for them while we were there, once we left, the VC came in and killed whole villages or would cut off their arms and legs. They were in the middle. This was the main image I wanted.

Several of my prints also involve helicopters, because they were like angels of mercy. Anyone who was in Vietnam always remembers the sound of the helicopters, because they could get you out of a really tight spot and save your life.

NEA: Are there any prints that you find particularly difficult?

SCHOL: Going Home is difficult. I went through a hangar on the way back from Vietnam, and I saw all of these caskets with flags…it's an image that no one was allowed to see publicly, because it was demoralizing. I was overwhelmed.

Fate and Finality are also tough for people to look at. It shows a soldier being shot and the second image is his spirit rising up. I've had a long-standing interest in graphic novels, and you can definitely see it here, depicting the spirit.

|

|

NEA: You dedicate your collection to John Richard Strong. Do you mind telling me about him?

SCHOL: John Richard Strong was in the Vietnam artists program with me, and we studied together in Austin. Neither of us knew the other was going to be there, so we really laughed when we saw each other. We were like brothers in Vietnam and were completely inseparable.

He came to see me a lot when we got home, because he was still dealing with the war. One day he came to see me, but I wasn't home, and then he went to his apartment in Dallas and took his own life. Sometimes I think I could've saved him if I had been home…. He'll always be so close in my heart.

NEA: What has been the response to Vietnam Remembrances?

SCHOL: Extraordinary.

PAM BURNLEY-SCHOL: We've heard a range of responses. One gallery reported that people often went in and then sat outside of the room and wept, and then went back in again. We've also seen that people were very contemplative, and a lot of veterans -- big, tough guys -- shed tears.

NEA: Was creating this collection cathartic for you?

SCHOL: Yes, I think so.

BURNLEY-SCHOL: I can tell it was healing for him -- not just to produce and process the work, but I've also observed that his acceptance of the responses from other people has been very healing for him. It was the kind of validation that he or the soldiers [never] got when they came back from Vietnam.