Five Things You Should Know About Environmental Artist Lorna Jordan

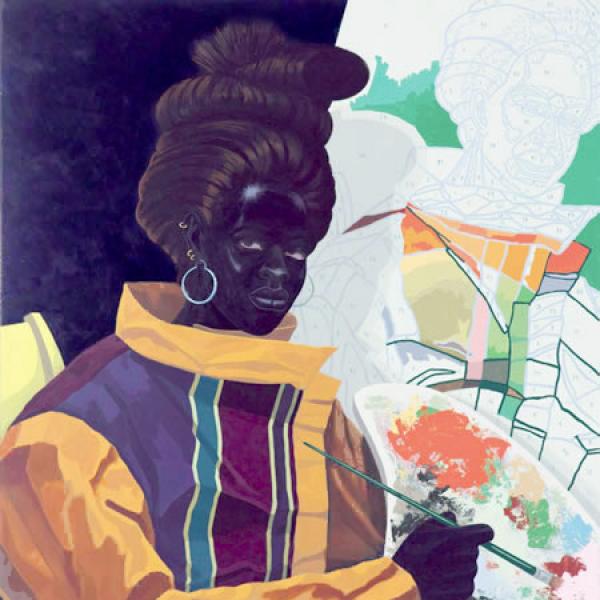

Lorna Jordan’s environmental artwork and theater garden Terraced Cascade in Scottsdale, Arizona—inspired by the marks that humans and water inscribe on the desert—expressed as both miniature watershed and abstraction of the human body. Photo by Lorna Jordan

Award-winning environmental artist Lorna Jordan makes work that is focused on connecting communities to their environments. Jordan’s projects are “situated within diverse contexts such as downtowns, parklands, ecological reserves, watersheds, buildings, and water reclamation plants.” Among her upcoming projects is the design of public art elements for the City of Madison, Wisconsin’s new Central Park, a commission that is being realized with the support of an MICD 25 grant from the NEA.

In her own words, here are five things we learned about Jordan during a recent conversation.

1. Lorna’s art practice is driven by curiosity.

I’ve always been really curious, and I’m interested in a lot of different things. I’ve developed an interdisciplinary approach to creating my work so I draw upon sculpture, ecology, architecture, infrastructure, and theater. My dad was trained as an engineer so I have that also in my background. I like to express a “systems aesthetic”—meaning that you’re thinking about ecological systems or transportation systems or park systems—and to really conceive a project as a total network of relationships, but expressed as art. I think about art as this umbrella in which all these different things can occur.

I started with a studio practice and showed my work in galleries and nonprofit spaces. I made sculpture and prints, and I was working with computers and video and making tableaux, which are small installations. I was exploring the intersection of public and private experience, and then over a period of about seven years I started working with the garden as a conceptual framework. I got interested in gardens because they’ve long served as a way of thinking about relationships with nature and culture and can be viewed as this balancing point between wild nature and human control. I was really intrigued by the hot debate—is nature a resource to be managed and exploited, like coal mining or tree farming, or a network of communities and systems to be balanced or a pastoral ideal to be preserved?

2. There is no one-fit-all version of public art.

I think public art [happens in a] pretty wide range of ways. Sometimes artists create a work that they then site in public, so that’s an object-oriented way of thinking about public art. Sometimes it might integrate a two-dimensional process, a mural for example, into a site. It can scale up from there to artists thinking about how places come about. I’m really interested in developing partnerships with agencies and nonprofits to get artists out there and working in as many ways as possible and to think of a whole constellation of approaches where artists are planners or they’re in residence in agencies or design team members or they work within the community—in community gardens, for example. Or they do guerilla theater or interventions, and so it’s beyond thinking about the object. It really is positioning artists as thinkers, catalysts, as designers and makers, and trying to avoid the silo problem. For me public art is not keeping art separate from everything else like the art goes here, the landscape goes here, the building goes over here.

3. Lorna thinks a successful project is a sustainable project.

I’m really interested in creating work that benefits the civic and ecological life of the community, and I like thinking in lots of different scales: a site scale, system scale, and even cities and regions and counties. I’m interested in thinking about experiential networks of systems, sites, and events that connect people to their community and the systems that sustain them. The qualitative aspect of making sustainable sites is sometimes overlooked. A lot of sustainable projects get points on paper; if you go down the checklist, you have everything, but they’re not necessarily all really great places. I think it’s really important to consider if people care enough about a place over time so that they’ll tend it and give it a long life.

I’m also interested in the idea of communities becoming engaged, not as spectators but as participants. I’m interested in sculptural expressions that embody cinematic progressions of forms that, in turn, are interacting with physical movements of people and natural processes. The idea is to immerse people in these environments…. Tapping into their memories and imaginations, they can have experiences that range from the scientific and observable to the archetypal and sublime.

The illustrative plan for Terraced Cascade. Image courtesy of Lorna Jordan |

4. According to Lorna, chaos is part of art…and so is listening and so is patience.

For me, a project first starts with learning about and developing the feel for a place so you’re engaging it and discovering systems and communities. I listen to people’s aspirations and explore a site and observe the ecological systems and read all sorts of documents and reports, considering what’s the possible meaning or potential it could have. And I’m also bringing in my own interests and experiences to bear. All these ideas and images and desires and facts and figures are swimming around in my mind, and it’s like this mental primordial soup. Chaos is part of it, and sometimes I feel overwhelmed by the possibilities. Then what always happens is there’s this glimmer that appears, and you kind of intuitively understand that there’s a concept that’s starting to come together. It can happen when you least expect it—you might be taking a walk or doing something else and, all of a sudden, the concept will come to bear and the layers start to deepen in your mind and you think, “Okay this is how I’m going to put this all together.” Then, of course, the next step is to test the concept and make sure that I can successfully make it happen. The process of making the kind of artwork I do takes a really long time, sometimes seven to ten years. So once you have an idea, it takes tenacity and hard work as well as creativity to make it happen.

5. Lorna’s work is her life (and vice-versa), and that’s just fine with her.

Some say you have to choose between your life and your work, but I think if you’re an artist that you’re more likely to make them one and the same. I’m so focused on creating environmental art work that addresses the possibilities of public space in the 21st century—whether it’s cities, parks, or ecological reserves—that this passion drives me as a creative person. I’m able to lead a life of ideas and studying and writing, and I get to explore sites and live in my imagination and then to collaborate with people and design and build and advocate for great places so there’s not really a separation between [life and work] at all.