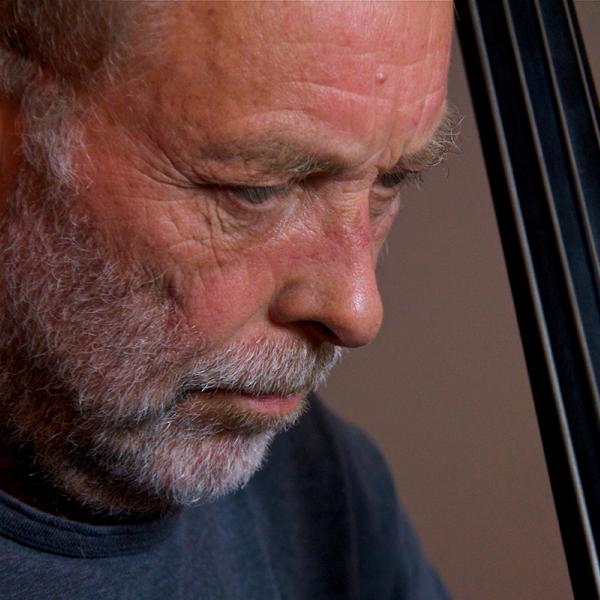

Thomas W. Jones II

Thomas Jones II Transcript

Music Credits: “Lord, I Just Can’t Keep from Crying,” and “Hear Me Callin’” from Bessie Blues, written by Thomas W. Jones II . Musical Direction by William Knowles . Performed by Bernardine Mitchell, Roz White, Lori Williams, TC Hawkins, Stephawn Stephens Djob Lyons, LC Harden Jr. and Nia Harris .

Bernadine Mitchell: Lord I just can’t keep on crying sometimes. Well my mother, she’s a sure eh that I’ve gone up on my way, my father, he’s gonna cheewa, my brother, he could not stay. I tuck him in every day. That Chattanooga burning way. Lord I just can’t keep on trying sometimes. Lord I just can’t keep on crying sometimes. With my heart full of sorrow,

Jo Reed: That is Bernadine Mitchell in Bessie’s Blues, which was written and directed by Thomas W. Jones II. And this is Art Works the weekly podcast produced at the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed.

Bessie’s Blues, starring Bernadine Mitchell, opened 20 years ago at studio Theater in Washington DC where it tore the house down. It was nominated for 7 Helen Hayes Awards and won 6, including one for its director Tom Jones. Well, Tom and Bernadine joined forces again and have just remounted Bessie’s Blues at Metro Stage, where it is once again, a rousing hit.

But Tom Jones isn't just a writer, director, choreographer, lyricist, producer and co-founder of a Black Theater Company; he's also an actor who went straight from directing Bessie’s Blues at MetroStage to the Woolly Mammoth Theatre where he is rehearsing the part of Mike in Lisa D'Amour's new play, Cherokee.

Thomas W. Jones II is a man of the theater, a living theater that seeks to break down barriers and start an audience wondering and thinking. He's also immensely successful at it. Even though he makes his home in Atlanta, he's been nominated for the prestigious Washington DC theater honor, the Helen Hayes Award 45 times, and he's won 15. Not a bad record.

He kindly agreed to be interviewed at the end of a long day of rehearsal and even arranged the room we used at Woolly Mammoth (note to listener: this is unusual).

Given his involvement in so many aspects of theater, I wondered whether his family were theater folks, if he grew up around actors?

Thomas W. Jones II: I did grow up in a family interested in theater. No one in my family actually did theater. My mother had always wanted to be an actress, ended up being a social worker. So growing up, we saw everything that was possibly done, whether it was community theater, Broadway, I'm a native New Yorker. So we saw everything, and then went I went to school, at that point, way back in 19-something-or-other, Broadway tickets for students were like four dollars. So, there was a period of about four or five years, from I think the seventh to the eleventh grade, where I saw just about everything that was opening on Broadway, and certainly everything that was African-American-themed. But just literally everything on Broadway, from "River Niger" to "Misanthrope." I mean, so it just, it was soup to nuts. We saw everything.

Jo Reed: Did you know this was what you wanted very early?

Thomas W. Jones II: Had no idea.

Jo Reed: You didn't?

Thomas W. Jones II: Had no idea. No.

Jo Reed: You just loved it.

Thomas W. Jones II: I loved it. I loved going to the theater. I wanted to be, I thought, a writer, and I was convinced that I should then probably be a lawyer. So I went to school just, and was a political science major, studied political science, had always been writing, writing poetry, writing short stories. Studied with Sonia Sanchez, who was also kind of someone who I deeply admired in high school, and particularly during the Black Arts movement. So you read all of those poets, Baraka and Nikki Giovanni and Sonia Sanchez and Haki Madhubuti, and the whole litany of Black Arts poets, and particularly those that were coming out of Broadside Press in Detroit. And when I went to school, to Amherst College in Amherst, Massachusetts, studied with Sonia for a year, decided at that point that maybe I wanted to be a writer. Then I went, took a year and was at University of Chicago for kind of an exchange, and saw a buddy of mine in high school at a play at Kuumba Theater in Chicago, Van Gray Ward's old theater, and at that point it hit me. The cloud parted and I said, "I want to do this." So I went back to school at Amherst and changed my major from political science to theater, until the last two years, and then left, once I graduated from school, started a theater company in Atlanta and ran that for 22 years.

Jo Reed: Did you want to be on the stage? Did you want to direct? Did you want to write plays? What was your entrée in?

Thomas W. Jones II: Initially, it was, I thought I wanted to be just an actor. But I had been writing, so I knew I wanted to write plays as well. I wanted to write as well. And then I was actually in a student production, I can't even remember the play, and I was deciding that actors should go here, and somebody should go there, and this should happen this way, and I was kind of really argumentative and probably a bit of a snot; and the director, who's really a good friend, came and said, "You know what? If you have all these opinions you should probably direct." So I took a directing class and then I decided at some point when I was going to graduate school that I wanted to kind of study to get my MFA, and they said, "Well, you can't really do three. You have to do, you have to kind of focus on one." At that point I said, "Well, maybe I then want to take a break from school and see if I can't develop this institution, theater, which would allow me to do all three." So one just kind of followed the other.

Jo Reed: What was your first experience in the professional theater, as a director, writer, or actor? What was the first time up?

Thomas W. Jones II: Well, as a professional it was actually, I'd done a senior thesis called "Every Father's Child." When I was a junior in college my father was terminally diagnosed with cancer, and I'd left school for a minute to take care of him. When I went back to school I actually wrote a piece about a man coming to grips with his own mortality called "Every Father's Child." When I left school, we actually started a theater company called Jomandi, J-O being Jones, my last name; M-A, Ma, for my other; A-N for Andrea, my sister; D-I for Diana, my other sister. We found out a year after we put it together in one of the ancient Senegalese dialects it meant "people gathered together in celebration." Yeah, it was kind of cosmic.

Jo Reed: That's fantastic. Yeah.

Thomas W. Jones II: But we put that initially together to endow a scholarship fund in his name at the School of Medicine at Morehouse College. My father was a physician. So that was kind of the organizing principle around the theater itself. It was a family effort to endow a scholarship. So that was my first foray into I think at least theater in a community, outside of an academic setting.

Jo Reed: Oh, that's so interesting, because I thought you did that further along in your career, but this was really so early in your career.

Thomas W. Jones II: No, no. That was the genesis. That was,

Jo Reed: And that, of course, has become one of the great African American theater companies in the country.

Thomas W. Jones II: Well, we were for a long, long time. I folded in 2002, I think about two years after I left. But yeah, from 1978, I graduated June of '78; we did the play initially in August of '78; and then incorporated in October. I went to school, I was going to Villanova for about a month, decided I really wanted to come back home, or to my new home, Atlanta, Georgia, and kind of continue the effort of what this institution was; and so went back home and, along with my partner, Marsha Jackson, we kind of put the theater together and such. So that was the genesis of it all.

Jo Reed: Were you always interested in musicals, too, or theater in general? Because you really do work in musicals a lot.

Thomas W. Jones II: I do, but a lot of our early work was looking at theater in a non-traditional context, was really kind of exploring form and structure and kind of getting inside of it, and I think a lot of that developed because we were such students of the Black Arts movement and there was so much of the idea of redefining theater, theater coming into a community, theater being, particularly from an African American aesthetic, using and conjoining all of the different elements, music and dance and poetry, and that theater didn't have to be linear or the four chairs and a table, that you could begin exploring and playing with form. And then I went to school, again, when I was at Amherst, it was an amazing, UMass, which is one of the Five-College Consortium, had the first Master's in Jazz program. So up there was Max Roach and Archie Shepp and Vishnu Wood, James Baldwin, Sonia Sanchez was there, Yusef Lateef. Diana Ramos was running the dance department at UMass, so we would see these productions, or these events, where you'd have James Baldwin reciting, Sonia doing a poem, Diane McIntire doing something else, and then you'd have Max Roach playing drums and, I mean, it was these incredible kinds of experiences. So it would kind of shape your sense of, or at least early on shaped my aesthetic, that theater was multidisciplinary, or that performance was multidisciplinary. So I think a lot of our early work in Atlanta, at Jomandi, was beginning to continue that exploration. And also when we got there it was at the height of the second generation of African American theaters, so there were nine black theater companies when I was in Atlanta in '78, '79. So a lot of what we were doing had to be, you know, what was going to be our niche? How did we differentiate ourselves from the theaters that were doing, quote-unquote, the four chairs and a table, that were doing Lorraine Hansberry and Phillip Hayes Dean and doing that canon of literature? What were we going to do? So we just continued I think our exploration of that, and out of that came the growth and the love of music and how it played itself, even in traditional, conventional drama, of beginning to eliminate the idea that there should ever be a blackout, that the theater experience should never kind of disengage and audience, so that you continue the idea; and so music became very prominent in how it is that we kind of put pieces together.

Jo Reed: Let's talk about the musical that you created 20 years ago,

Thomas W. Jones II: Yes.

Jo Reed: That's playing right now, and that's "Bessie’s Blues." That opened to enormous praise and was equally well praised again. What was the origin to that particular piece of theater?

Thomas W. Jones II: I was a huge fan of the woman who's actually the lead, named Bernardine Mitchell. When I got to Atlanta, she was this amazing club singer. She was, to me, the second coming of Nina Simone, in the way in which she phrased her voice, and she was also an actor. So, I decided at some point, you know, I approached her, said, "I want to write a piece for you, just to showcase you, because I'm such a fan." And she said, "Well, I've always wanted to do a piece on Bessie Smith," and I was like, "Well, I'm not sure I'm totally interested in just doing a biography on Bessie Smith," but what if we were to look at it, in a certain sense, as looking at the black artists and the blues cycle through the 20th century, through the lens of two women, and parallel where blues as an art form comes from, and I think particularly it also continued the idea of at that point LaRoi Jones or Imamu Baraka, blues people, the sense of that a people create an art form, a functional art form, in a certain sense to organize the chaos of what it is to be Negro and American and all of that. So I think we wanted to kind of follow that line, that linearity, and then creating a piece again in that same tradition of not being linear, not being linear in the storytelling, but that it was about it then. So we actually structured the piece like a blues, you know, so you would start in the present tense, you would go back to the past and you'd come back into the present to kind of reassert whether it is that what you saw in the past was true, much like an 8-bar blues. "She may be your baby, but she comes to see me sometimes. She may be your baby, but she comes to see me sometimes. She comes so often, I think she's mine." Which is actually, in a kind of standard 12-bar blues, it's the idea that you state the idea; you begin to then restate it to make sure that what it is you're seeing is what you're seeing; and then you begin to try and find a solution to it. Which is actually just what the construct of the blues is, and it follows in a certain sense the ethic of a people trying to organize the chaos of coming out of slavery, coming out of American oppression and what does that mean. You organize it. Is what I'm seeing what I'm seeing? Yes, that is what it is. Now, what's the answer to that? How do I get through that? So the blues in a sense as an art form and as an ethic is, it's not about depression or being sad, but it's really about an ordering construct, an organizing idea about how it is that you can manage whatever the events are in your particular world. So the construct of "Bessie’s Blues" itself is exactly the same. We start with the idea of stating what it is: "I'm in a particular kind of pain." I go back to the past and say historically that pain has always been here; and now what do I do to kind of manage that and find a bridge across that?

Jo Reed: "Bessie’s Blues" has some '30s songs. Some are classic Bessie songs, but most of them were written by you and Keith Rawls. Why the decision to do that?

Thomas W. Jones II: Well, I think a lot of the work that we wanted to do in a contemporary context was to have an original score, and so that you balanced what an original voice would be, vis-à-vis Bessie's voice. So there are very few songs, once you go back, in terms of looking at Bessie's life, that are original. All of that follows in a sense her canon or at least the canon of a kind of blues motif at that time, minus a song or two that we tried to create a contemporary score so that the two were balanced against each other so that there was, in a certain sense, a world into Bernardine that was unique and distinct from the world that was Bessie Smith, and so, a song in the present day, which was about Midnight and being lonely would certainly counterbalance when you went back and did "Give me a pig foot" or whatever that corresponding musical idea was in the '20s.

Jo Reed: There was some funk, there was a lot of R&B, there was certainly jazz and swing, hip-hop? And I thought it was a very diverse musical palate, but at the same time, as an audience member, I thought it was also really instructive because I'm seeing this blues line that's really going through all the music, and you see,

Thomas W. Jones II: Absolutely.

Jo Reed: "Oh, no blues, no hip-hop."

Thomas W. Jones II: No hip-hop. Right, there's no blues, there's no Louis Jordan; if there's no Louis Jordan there's no James Brown or Chuck Berry; if there's no Chuck Berry then there's no, there are no Beatles; that in fact we simply build on the backs of what kind of the historical precedent is musically. And so it is, so it's the idea of looking at Tin Pan Alley songs, or those kind of incantations that you would hear Sterling Brown or Langston Hughes do, "Jump back, baby, jump back", it's no different than when you hear a hip-hop artist saying, "And out to the club and I went", that the rhythms are built on top of each other, and that you may change the accent and the inflection or you may look at it differently, but jazz is just blues moved to the city. It's just, just like, you know, gospel is just spirituals that went up north, that the music changes because the impulses that give birth to it change.

Jo Reed: 20 years ago, "Bessie’s Blues" opened at Studio Theatre. Rave reviews, six Helen Hayes awards, including one for you for director. Now, let's fast-forward 20 years. Why remount it now at Metrostage?

Thomas W. Jones II: It was interesting. A couple of years ago, Bernardine and I were doing a show in Atlanta, another show that I actually written, at a theater called Horizon Theater, and we were just sitting on a break and I said, "Do you have another Bessie in you?" She said, "I think I got one more." I said, "Okay, well let's see if we can find someplace to do it." Because it's such a, I mean, it's such a huge kind of theatrical piece to put on your back and have to walk for two hours,

Jo Reed: Even when she's not on the stage, she's on the stage.

Thomas W. Jones II: She's on the stage. She is, yeah. And literally, when she's not on stage, she's just changing. I mean, she has all of about, you know, 30 seconds to change and get back and then kind of move the next, move that boulder uphill a little bit more. And so we were looking for someplace to it, and, you know, luckily MetroStage has been a home for the last 10, 15 years. And, you know, Carolyn said, "Well, you want to do it here?" and I said, "It would be great." So, it was kind of a natural fit I think in terms of remounting it. But also, just to look and say, "Is the play still relevant? Does it still have resonance? Does it still have texture?" Certainly the music does, but is what it's saying still relevant? And it really hit us one day: there's a line at the end of the show, that Bessie matters, and all of us just stopped and went like, "Wow." It was the context of hearing "Black Life Matters," and you realize that, you know, something that was written 20 years ago still, in a certain sense, is crisply new because I think we're still dealing with the same kind of debate of: does our life matter, and if it does, why and how, and how do we articulate that in the world?

Jo Reed: The amount of talent on that stage was pretty spectacular.

Thomas W. Jones II: Yeah, it was.

Jo Reed: And the music was wonderful, and that was William Knowles?

Thomas W. Jones II: Yes.

Jo Reed: Who was the musical director.

Thomas W. Jones II: We first met 20 years ago the Studio Theatre. He was initially the keyboard player. There was, our musical director, Keith Rawls, when we did it in Atlanta was, God rest his soul, he passed a couple of years back, he was our musical director in Atlanta. And there was a white guy who had created a funk band called Ripple, for those of you going way back in the '70s, named Dave Ferguson, and he became our, he was our musical director up in D.C., and we kept looking for the right musician. And Dave is kind of ADHD. You know, he's got about, he has about a 20-second attention span. I mean, it's like "No, that's not right. No, that's not right," and Joy Zinoman, the artistic director at the Studio, was getting frustrated. "Well, we don't, we're running out of musicians who can possibly do this," and Dave would just, "No. Not right. Not right," and ran out and smoke a cigarette. And he'd come in and, "Well, why don't you listen to him?" "I could tell on the first one. It's not right." So the story William told me years later that, he said the woman he was dating at the time saw the little billboards at Studio Theatre and said, "Hey, you should go audition for this. They need some blues and jazz musicians. You probably will fit in." So he walked in. He was fresh out of, in fact, he went to UMass, had his MFA in jazz at UMass, and walked in, and he played about, maybe about 30 seconds. Dave said, "That's our guy." And, as it turned out, he was right. He knew what he knew. And so that's what, where I first met William.

<music>

Jo Reed: What was it like to see Bernardine Mitchell as Bessie again?

Thomas W. Jones II: Oh, it's just thrilling. It's just thrilling. And to, her voice is as good as it's ever been, but the kind of gravitas that she now has 20 years later from having lived it, that it deepens. It's deepened the music, it's deepened her sound. Her acting is just ordinary. So I mean, she just, she takes you on a ride. I mean, she really does. And so watching her do it again, it's even more thrilling now I think than it was 20 years ago, and I was pretty thrilled then.

Jo Reed: Is it different when you're directing your own work than when you're directing somebody else's? Is your process a little, do you approach it differently? I'm just curious about that.

Thomas W. Jones II: Over the years, it isn't anymore. I really have no ego about my own stuff, at this point, and if it works it works in the mouth of an actor; if it doesn't, just get rid of it, let's do something else. You know, I think it's a little more freeing because I don't have to necessarily check with the playwright whether I want to change something, you know. So it's quicker, in a sense. If you hear it immediately and go, "Okay, I don't have to work through that. Let's change it. Let's get rid of that. Let's figure that out." But I don't think the process for me is any different. It's a text. It has to live in the mouths of actors. It has to make sense. They have to kind of walk with it and put it on as a piece of clothing that fits them well. It doesn't in that sense. The only difference in writing it, you know, which I've often had complaints about is I don't write a lot of stage directions because I know I'm going to direct it, and I know the trick that playwrights have of writing enormous stage directions simply because they're trying to direct it from, you know, their laptop. It's not like, they're a clue to what's the playwright's thinking, but you're not going to do what the playwright says parenthetically. You know, you really are going to figure out what the mechanics of that, but it gives you an insight as to what they were thinking. I can leapfrog that process because I know what I'm thinking. Or I want to step away from it because I don't know what I'm thinking and I want to see it as objectively as I can as just a piece of dramatic literature, and "How does this play".

Jo Reed: And while all this is going on, "Bessie’s Blues" just opened in Alexandria at MetroStage, you put on your actor hat and came over to Woolly Mammoth where I am speaking to you, and what are you doing here?

Thomas W. Jones II: Doing a glorious new play, "Cherokee," by Lisa D'Amour, she was the author of "Detroit," which I think played at Woolly quite, quite successfully, and I think she's exploring a new piece, which is quite adventuresome, and it's fun to be a part of the process. I've come in somewhat late, in the sense that they'd been workshopping this piece at Woolly since it left the Wilma Theatre, and, you know, a lot of the actors have been with the play for a minute, so I'm kind of coming in kind of fresh and new. But it's quite exciting because I think she's dealing with some things that are, in terms of form, in terms of structure, and even in terms of content, that I think are important to hear. So it's kind of fun to go on the journey. It's not "Detroit," and so if you come thinking it's "Detroit," then I think you'll miss the vitality of what it is that she is trying to do.

Jo Reed: Can you tell us just a little bit?

Thomas W. Jones II: Yeah, two couples on a hiking trip, and one white couple and a black couple, and the black couple, guy named Mike, leaves, steals away into the woods and is just missing, and then returns as someone completely different, almost with no memory of who that was, and what then happens in terms of once you ask people to one, live a life without fear, live a life without boundaries and to open yourself up and be available to a whole new sense of what freedom might mean to you, and inherently how frightening that can be, you know, in terms of losing things like gender and identity and the creature comforts that you have, that you hold onto, because it defines who you are, how do you let go of that and become someone new? And what that, it's kind of freefalling. So there's something that's really kind of thrilling about trying to take that on and figure that out.

Jo Reed: Is it freeing for you to come and be an actor, and put down the director hat?

Thomas W. Jones II: Oh, it is. To some degree. Yeah, absolutely.

Jo Reed: I mean, I can see how it could be a little difficult too, but I could also imagine, like, "That is his problem."

Thomas W. Jones II: It absolutely is. I don't, I try and stay in my lane when I'm an actor. It's like, "This is my lane. This is what I'm supposed to be doing," and I try and stay as rigidly in that as possible. And there are times when things creep in where you say, "Oh, I would probably do that differently," or "I would" or, "Hmm..." where you start conceptualizing it like a director, and then have to shut that down like, "No, no, that's not your gig. That's not what you do. You should be over here hitting your mark, saying those words, and making sure that you're intelligent and intelligible."

Jo Reed: Is there a certain joy you find when you're onstage?

Thomas W. Jones II: I do. I hate acting in terms of once the show's up. I just hate it.

Jo Reed: "Day two."

Thomas W. Jones II: Oh, day two, right, right. As soon as it opens I'm like, "Okay, let's do something else. We've done that.” “No. You, young man, have four or five more weeks of this." "I don't want to do four or five more weeks of this. I did it last night." And then my creative ADHD: "I want to do something else now." So there's, I experience that because I think the older I get the more I enjoy the process of discovery, and I think I like the rehearsal process, which is why I think I enjoy directing as much as I do writing, because you're in the process of constantly discovering, and then that goes away at a certain point once, obviously when you're in front of an audience and you have to kind of replicate those experiences. And so, the margins of what you discover are far more incremental. They're delicate. You find a little thing here and a little thing there, but for the most part you've tried to set a performance and a way of approaching it that doesn't dramatically differ in week four from what you opened with.

Jo Reed: As a director, do you go back to your shows when they're up and occasionally go sit in the back?

Thomas W. Jones II: No. I'm done. No. Done. Done. I don't even see opening night. I haven't seen an opening night show of mine in 25 years.

Jo Reed: Really?

Thomas W. Jones II: No. I haven't, I just can't.

Jo Reed: Not even "Bessie’s Blues" 20 years ago?

Thomas W. Jones II: No. I've seen it in previews because I know the next day I have to go to work. You know, I'm looking for what's not working or trying to negotiate and manage what's going on here, and you go into the next day. Once there's no work to do the next day, it's too agonizing. In fact, it started years ago when I was running Jomandi and I was, that I would sit in the back of the theater, and then I was a chain-cigarette-smoker. I've since given up cigarette-smoking about 20 years ago, so I was always running in and out of the theater. I was smoking and I was running out and running in and, and the subscribers started complaining to the box office. "There's a man who smells like tobacco, and he's a little annoying because he keeps grunting and, ungh, agh, and we can't really enjoy the play." So I said, "You know, I don't need to take myself through this agony," or the temptation of wanting to give actors notes after, you know, the first night, and you're like, "That's unfair to them," you know, that at some point you have to release them and trust that whatever you've done in that four weeks is what it is, and if it's not working, you're not going to be able to fix it with a note in a night. And particularly with new work, when you're discovering what's not happening, having to build in, which is what we started doing, future productions, so you could go back and work on them. If it's not working, okay, it doesn't work, you got it. Fix it the next time out, but you're not going to fix it in this production necessarily, so let it go; and so part of my letting it go was just refusing to see it. And I used to lie to actors, "Oh, yeah", I'd listen and hear what audiences were saying about certain moments, and so when they'd come, "Did you see?" "Oh yeah, when you came out and", someone just finally busted me: "You weren't there." "All right, I wasn't."

Jo Reed: Tell me why you think it's important to have companies that tell stories of African Americans and the African diaspora, why that space is still so important and necessary.

Thomas W. Jones II: Well, because I think you're in a constant state of evolving as a people, and if you don't have a sense of a context, one, of where you come from, or what it is that you're trying to reckon with now, or how it is that you're ordering a certain world of chaos, or how it is that you take your children and say, "This is, in a certain sense, part of the traditions that you come from," or "These are the issues that you're dealing with," or "These are the things that may help give you an insight into why it is you feel the way you feel, why it is that you're going through what you're going through. This is, in a certain sense, a point of view of that may help you order the universe." If you don't have that then, in a certain sense, there's a certain disconnect between you and what you're going through. I think the wonderful thing about theater is that, at its heart, its storytelling, and that part of storytelling is where you begin to understand values and myths and legends and your sense as a hero or as a "shero" in the world. I mean, you begin to say, "Okay, I matter. I have value, because someone chooses to talk about me and my life and my existence in a certain way. So therefore I have context. I have a place that I matter on this earth." That’s true of any culture, and it doesn't have to be theater in the most traditional and conventional sense. It's important to have institutions, but in the same way when I was a kid sitting at the feet and listening to my grandmother and my grandfather, my father and my uncles, talk about their lives and where they were going and laughing, and you get a sense of, "Oh, there's something that happened before me that was important, that got me here." Knowing that is certain grounding. And then it means that you can kind of proceed in your life unapologetically, and that somebody else then can't define you for you. So then someone's notion of who you are as black or as male or as female or as gay or as straight doesn't really have traction because you've been able, in a certain sense, to negotiate what those stories are, what those values are, for yourself; and so therefore you, again, as Dickens said, you become the hero in your own life. You're able to articulate to the rest of the world who you are, or at least you have something to brace up when the world tells you that it's this, and you say, "No, it's not that. I have a context for something else. I have another point of view that says, 'No, I really am this.'"

Jo Reed: Do you feel in some ways that the conversations that were begun with the Black Arts movement you're taking and you're continuing into this century?

Thomas W. Jones II: Oh, absolutely. I think we're all, in a certain sense, a continuation of, in the same way that I think we're also a continuation of the woman's movement, and we're also a continuation of gay rights activism, that we're, in a sense, trying to figure out a context in this place called America, which is just an experiment, you know, at its heart, and when you look at European cultures, they are thousands and centuries and centuries old, and they've had a chance to evolve, and they're pretty monolithic in terms of where they are culturally. We have blended over 200-some-odd years blacks and Latinos and whites and Asians and Irish and Italians and said, "Okay, all of you now have to coexist and make this make sense." Really? And what's the precedent for that? Where do we begin to look historically and see where that's happened? You don't. We can see numerous examples of how, where cultures cannibalized each other and where they've tried to take over, you know, but the sense of how it is that you, under this thing called a democratic construct, coexist with all of these varied cultures, it's an extraordinary idea; it's an extraordinary experiment, and how do you make that make sense and make it work? And I think part of what theater does is create a context for a public conversation. So I think we're always in a sense, as theaters, an extension of the last generation, trying to continue that conversation. And where maybe years ago we were dealing with the Civil Rights Movement and what that meant, you know, and some of that, and maybe years before that you were dealing with women's suffrage, and maybe years before that you were dealing with the abolition of slavery, and maybe, you know, that in a sense it was each generation trying to say, "How is it that we take this grand experiment and make it make sense?" And so I think, yeah, we always I think are living not simply on the backs of other African American theaters, but theater in terms of all different kinds of cultures that are beginning to approach it from their lens about what it is to live and coexist and make sense out of the world.

Jo Reed: Tom, thank you so much.

Thomas W. Jones II: Oh, my pleasure.

Jo Reed: I mean, it was such a pleasure to talk to you. It really, really was.

Thomas W. Jones II: My pleasure. Thank you.

Jo Reed: That was Thomas W. Jones II. Bessie’s Blues is running at Alexandria's Metro Stage through March 15, and you can see Tom perform in Cherokee at DC's Woolly Mammoth Theatre until March 8.

You've been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter.

For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Transcript will be available shortly.

Makes sense of the world through theater.