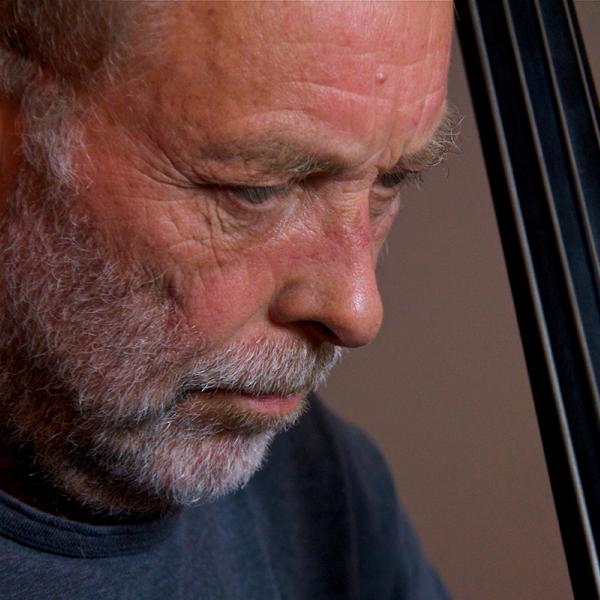

Sean Wilentz

Transcript of conversation with Sean Wilentz

"The Times They Are A-Changin'"

Come gather 'round people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You'll be drenched to the bone.

If your time to you

Is worth savin'

Then you better start swimmin'

Or you'll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin'.

Jo Reed: That was Bob Dylan singing "The Times They Are A-Changin'." Welcome to Art Works the show that goes behind the scene with some of the nation's great artists to explore how art works. I'm your host Josephine Reed.

The times certainly have changed but Bob Dylan has endured as a major figure in American culture for five decades. This week, we mark his 70th birthday. Bob Dylan is a singer, songwriter, poet, performer, musician and painter. He wrote the anthems for a generation, perfectly articulating the discontent and the hope of the 1960s. But Dylan never stood still; he always evolved. Part of his power is his ability to take music and make it into something completely his own. His lyrics are often poetic, married to melodies that underscore their meaning and delivered with a voice that's imperfect and unforgettable. Dylan is acknowledged as a master songwriter and performer; among his many awards and honors was a special citation from the Pulitzer Committee in 2008 for his "profound impact on popular music and American culture" and in 2009 the National Medal of Arts which he received from President Obama.

Dylan has been the subject of many autobiographies, most recently, Bob Dylan in America which was written by the Princeton cultural historian Sean Wilentz. Wilentz may be a historian, but he's no musical novice. He's a received a Deems Taylor award for musical commentary and a Grammy nomination for his liner notes to Bootleg Series: vol. 6 Bob Dylan: Live 1964: The Concert at Philharmonic Hall.

In Bob Dylan in America, Wilentz looks at Dylan's music both within the context of its time and within the stream of American culture that reaches back to Aaron Copland, Woody Guthrie, and Blind Willie McTell. In the first of a two-part interview, I talk with Sean Wilentz about Bob Dylan's influences and early career. I began my conversation by asking Sean why, as an historian, he chose to look at Bob Dylan.

Sean Wilentz: Well there are a bunch of answers to that, Jo. In part it's because I grew up in a very peculiar time and place. My dad and his brother ran the Eighth Street Bookshop in Greenwich Village on the corner of Eighth Street and MacDougal in the 1950s and 1960s which was the literary- downtown literary crossroads. Every writer in New York came through there including the beat poets like Allen Ginsberg and the others. And it was kind of, you know, a hip spot, hip literary spot and it was also just down the block from where the folk revival was getting started in the 1960s which Bob Dylan was very much a part of. So I grew up in that world and was very much there. My dad in fact got me tickets to see a Bob Dylan show in 1964. He was the first one to give me a copy. He gave me my first copy of Blonde on Blonde. I mean it was a very strange upbringing. I just thought it was normal. So that's one reason; it's been around in my life and in my soul I guess since I was very, very young. But the other reason is the way I write as a historian. I am an academic historian in the sense that I teach at Princeton and I certainly train professional historians but much of my writing or I've tried to aim my writing at a broader audience and I've written a great deal for journals and magazines and so forth. I have a kind of double life or double career as a writer. So writing this kind of book isn't so odd for me given all of the writing I've been doing, especially my writing about Bob Dylan.

Jo Reed: The title of this book is Bob Dylan in America and you read him as an American artist, part of the stream of American culture.

Sean Wilentz: Well you know I mean Dylan comes out of the heartland of America or he comes out of what people call the heartland. He comes out of Hibbing, Minnesota, a dying mining town in northern Minnesota. Very much aware of American music. American music is what turned him on to music in the first place, listening to it in all kinds of situations. Listening to it late at night as the radio stations from Shreveport, Louisiana would beam in all of that music, rhythm and blues and all kind of things that you weren't going to be hearing in Hibbing, Minnesota but other things too, the pop songs of the 1940s, the polka songs of the 1940s. All of this was around him very early on, he was picking up on it, and then of course he got interested first in Little Richard and rock-n-roll but then very deeply in Woody Guthrie. And from the very start of his career American song and American poetry gave him his American voice. And since he has been a student- he doesn't just restrict himself to American materials, but he's very, very interested in not only the stuff of American culture, but of this whole kind of mythic America that kind of exists now but doesn't. Certainly it existed in the past although not quite as people remember it. An America of factory towns, in America of circuses, traveling circuses, in America of Edward Hopper-like scenes. He wants to try and conjure up all of that that's very much a part of American life. And as I say, make it his own, I mean turn it into something else. But it's distinctly American. He's speaking out of America to America and then ultimately to the world.

Jo Reed: So how much of an historian is Bob Dylan?

Sean Wilentz: Oh Bob Dylan is an amazing historian actually in a funny way. He describes in his wonderful memoir Chronicles Volume One about how he was actually listening to the Clancy Brothers at the Whitehorse Bar on Hudson Street, New York and listening to all the great old Irish rebel songs like Kevin Barry, "The Minstrel Boy" and so forth, and how he was very excited by all of them but they didn't connect with American life. So what did he do? He went up to the New York Public Library and started reading microfilm copies of old newspapers from the 1850s that were describing how the nation was lurching towards the Civil War. And he says in his memoir from that experience he really found the template for all the rest of his music coming out of the death and transfiguration of a nation. Now not all of the songs are about that, obviously, but I think he understands a good deal about American history. He reads American history closely. He has written historical songs, songs that actually deal with Civil War themes, so he's very well aware of it. The thing about Dylan is he can take the past and the songs of the past and the sites of the past and the myths of the past and make them seem as if they are present. He can have them inhabit the present so that the past and the present don't look so different from one another. He can take an old, I don't know, an old fiddle tune and turn it into a different kind of song that is speaking to today but is also lodged in the past. So he's kind of breaking down the difference between them, the distance between them, giving you a kind of timeless magic zone where it can be 1850 and 1930 and 2010 all at the same time. He does that in his songs but you have to know a lot about the past to be able to do that.

Jo Reed: You begin your book by telling stories about other American artists and I think most of us would be forgiven if you would have started with Woody Guthrie, but oh no, you went, you began with Aaron Copland.

Sean Wilentz: Yeah.

Jo Reed: Tell us how we began there.

Sean Wilentz: Yeah. Well I began there in part because I just didn't want to do Woody Guthrie again. I mean the stories told about Guthrie's influence on Dylan are pretty familiar. I had very little to add about all of that. And I didn't want to denigrate Guthrie in any way but I just didn't want to do what everybody else had done. But what I was interested in doing is finding out more about the cultural world of which Guthrie was a part but not just Guthrie and not just the people around him, directly around him like Pete Seeger and Cisco Houston and others, but rather a bigger conjuries of American life in the 1930s and 1940s, both political and musical that was going to create the folk revival, the first folk revival really of the 1930s and 1940s which would then help spark that which Dylan took part in, in the 1960s. So I wanted to get this bigger world of basically left wing music making in the 1930s and 1940s. And along the way I happened upon a review that was written about Aaron Copland given at the he gave a performance at the Composers Collective which was basically a Communist-affiliated music group which he was hanging around with. And the review was in The Daily Worker and it was a rave review written by one Carl Sands who turned out to be Pete Seeger's father, Charles Seeger. And then I found out that Charles Seeger actually dragged his kid along to hear Aaron Copland discourse at this little club. There were connections between Aaron Copland, the world of Aaron Copland, the preoccupations of Aaron Copland, the political thrust of his work and what was going to be going on ending up with Woody Guthrie and the Almanac Singers and all the things that we're familiar with. So what I wanted to suggest or what I wanted to try to work out was some of the connections between Copland's very different kind of musical experience creating orchestral music out of all of that rather than folk music, but using folk music and elevating it to a kind of orchestral art in a way that Dylan was later to take American folk music and while not doing orchestral music but certainly singing other kinds of things also raising them into a different kind of art. But the impulses that were very much around Aaron Copland were impulses, the same kinds of impulses that were affecting Bob Dylan so I wanted to try and make the connection that way. So that whole world did have an effect both direct and indirect on what Dylan was up to.

Jo Reed: And Aaron Copland's music at least was sort of an opening act for Bob Dylan after 9/11.

Sean Wilentz: That's right, Jo. That's the other connection direct connection that's there. Just after the attacks of September 11th, 2001 when Dylan opened a tour in the Pacific Northwest he began playing at some point in that tour he began playing this kind of call to order his recorded music that means the concert is about to begin, and began playing Copland's "Hoedown" from Rodeo ...

Up and hot.

So there was obviously Copland meant something to him. He wouldn't be there if it weren't. And also what the other connection there was that that particular tune, "Hoedown" had first been recorded in the 1930s. It was being played by, it's the version played by a Kentucky fiddler named William Hamilton Stepp and it happened to be recorded by Alan Lomax who was very, very much a part of that old folk world. So here was a song that came out of Alan Lomax, was transformed by Aaron Copland, and then it ends up starting a Bob Dylan concert. There's a cultural circuit that I wanted to explain and explore.

Jo Reed: And let me just stick another spoke in that circle because here at the National Endowment for the Arts the person who was the first director of the Folk Arts Department was Bess Lomax Hawes.

Sean Wilentz: His sister, I think ...

Jo Reed: Yes. That's right ... . going back to John Avery is very important, and at the Library of Congress. Alan Lomax worked as basically he ran the folk song archive at the Library of Congress for many years and did a lot of very important work there.

Jo Reed: And the other cultural strand that you follow that preceded Bob Dylan but most certainly was an influence on him and on his work was the Beats, the Beat poets.

Sean Wilentz: Right.

Jo Reed: Most particularly Allen Ginsberg.

Sean Wilentz: Right.

Jo Reed: Less of a surprise.

Sean Wilentz: Less of a surprise. People knew about Dylan's connection with Ginsberg because it became a kind of, I don't know, they became the hippest friendship of the mid-1960s right if you were growing up in a certain part of New York. But Ginsberg was of an older generation. Was one of the leaders of the Beat Generation eruption in the 1950s. And actually going back to the 1940s when the whole thing began at Columbia University. Dylan read the Beats. In fact I just found out he read a book that my father edited called The Beat Scene. I hadn't known that, but in the little circle that he was in in Minneapolis when he was living there before he came to New York that book was around. At any rate, the Beats were there but Woody Guthrie took precedence so he kind of put the Beats aside. The think about Dylan is he never rejects anything. It's always there for him to go back to. So in late 1963 when Dylan was kind of at the end of his rope in some ways artistically and esthetically, spiritually, he begins going through certain changes and ends up writing lyrics that are much more in an impressionistic and clearly Beat generation influenced vein. He happened at that point to meet Allen Ginsberg for the first time actually again the memoir bit comes in, in my uncle's apartment above the bookshop, that's where that meeting took place. And they became friends and remained friends until Ginsberg's death in 1997. But I wasn't interested just in tracing the friendship although it's fairly interesting but in looking at the ways that Dylan's work was deeply affected by Beat prosity and what they had originally called "the new vision" in albums, particularly on Highway 61 Revisited. You can see it beginning in another side of Bob Dylan and in "Bringing It All Back Home" but particularly in "Desolation Row" where specific lines come out of a book that Jack Kerouac had published that very year, 1965, called Desolation Angels, direct lines are taken from there but also the spirit of songs like "Desolation Row" were very much I believe in the Beat vein.

"Desolation Row" up and hot ...

They're selling postcards of the hangingâ¨

They're painting the passports brownâ¨

The beauty parlor is filled with sailorsâ¨

The circus is in townâ¨

Here comes the blind commissionerâ¨

They've got him in a tranceâ¨

One hand is tied to the tight-rope walkerâ¨

The other is in his pantsâ¨

And the riot squad they're restlessâ¨

They need somewhere to goâ¨

As Lady and I look out tonightâ¨from Desolation Row

So in effect, Bob Dylan or the Beats, Bob Dylan picked up on the Beats to help him come out of one kind of Bob Dylan, one shape of Bob Dylan became another shape of Bob Dylan and the Beats in some ways were an influence, in some ways were actually a catalyst.

Jo Reed: As you mentioned this book is part memoir is not exactly right but there's a strand of memoir that's ...

Sean Wilentz: Yes, that's right.

Jo Reed: ... Woven into the story.

Sean Wilentz: Right.

Jo Reed: I think that's a better way of putting it.

Sean Wilentz: Right.

Jo Reed: Do you remember the first time you heard Bob Dylan?

Sean Wilentz: Yes. I do. I was and it was in church so explain that one.

Jo Reed: Go figure.

Sean Wilentz: Yeah, go figure. Well there are a lot of odd things about Bob Dylan and my relationship to his music. My little Sunday school, I grew up actually in Brooklyn Heights, the bookstore was in the Village but my mother refused to leave Brooklyn so I grew up in Brooklyn Heights. At my Unitarian Church group a young girl a little bit older than me can in with this record Freewheelin' Bob Dylan and the cover got me right away because it's that famous picture of Dylan with his then girlfriend Suze Rotolo walking down a snowy street on Jones Street in the Village. But the songs got to me too so I very much remember all of that.

Jo Reed: The Concert he gave in 1964 at New York's Philharmonic Hall was important and you were there.

Sean Wilentz: Yeah my dad got these tickets and me and someone else went to the concert and it was Dylan on the cusp of change. He was still playing with his harmonicas and his harmonica rack and his acoustic guitar, but he was kind of coming out of, he was very much involved in that shift that the Beats' work proved so influential in helping him make out of political songs like "Who Killed Davey Moore" or even "The Times They Are A-Changin'" into things like "Gates of Eden" and "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" which have a social even political side to them but where the language is much different, much lusher. As well as much more personal songs and much more introspective songs.

"It's Alright Ma"....Up and hot

Darkness at the break of noonâ¨

Shadows even the silver spoonâ¨

The handmade blade, the child's balloonâ¨

Eclipses both the sun and moonâ¨

To understand you know too soonâ¨

There is no sense in trying

Pointed threats, they bluff with scornâ¨

Suicide remarks are tornâ¨

From the fool's gold mouthpiece the hollow hornâ¨

Plays wasted words, proves to warnâ¨

That he not busy being born is busy dying

Temptation's page flies out the doorâ¨

You follow, find yourself at warâ¨

Watch waterfalls of pity roarâ¨

You feel to moan but unlike beforeâ¨

Discover that you'd just be one moreâ¨person crying

So don't fear if you hearâ¨a foreign sound to your earâ¨

It's alright, Ma, I'm only sighing ...

So Dylan is kind of performing in New York. He came which is a big concert the Philharmonic Hall, the biggest gig in terms of prestige I suppose, that he had given. And performed for us this mixture of things showing where he had been but very much showing where he was going in ways that bowled us all over.

Jo Reed: You spend a chapter on Blonde On Blonde.

Sean Wilentz: Yes.

Jo Reed: The recording of that.

Sean Wilentz: Uh-hum.

Jo Reed: Why? Let's talk about that. What was special about that?

Sean Wilentz: Dylan had recorded "Like a Rolling Stone". He had made his appearance at Newport. He was very much in his electric vein which got some people angry. It makes people think he had betrayed them. But he's continuing. He's pushing on and really very soon after all of that had happened at Newport, he goes into the studio in New York, he has one song really special song that he wants to record called "Freeze-Out" at the time which later became "Visions of Johanna" which is one of the truly great Dylan songs, right up there with any of them. He had that ready but he couldn't quite record it. He was using his then touring band "The Hawks" who later became "The Band" but things weren't quite jelling. He got some other studio musicians in to record one song that did work out, not "Visions of Johanna" but then moved down to Nashville. And in Nashville combined some of his musicians from New York, Robbie Robertson and above all Al Cooper his organ player and quasi musical director, and they met up with some of the most talented young session men in Nashville, and they created this extraordinary album Blonde On Blonde with songs, not only the recording of "Visions of Johanna" but songs like "Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands", and "Absolutely Sweet Marie" and all kinds of stuff in various different forms but coming down to what Dylan once called "a thin, wild mercury sound" that he was aiming for or that Cooper in fact just as evocatively calls "a sound of 3:00 A.M." They had the sound of 3:00 A.M. down really, really well.

"Visions of Johanna" up and hot.

Now, little boy lost, he takes himself so seriously

He brags of his misery, he likes to live dangerously

And when bringing her name up

He speaks of a farewell kiss to me

He's sure got a lotta gall to be so useless and all

Muttering small talk at the wall while I'm in the hall

Oh, how can I explain?

It's so hard to get on

And these visions of Johanna they kept me up past the dawn.

Sean Wilentz: And it's an extraordinary album but about which there has been a lot of myth generated and that's kind of clung to it like barnacles about how that particular album was made. So I wanted in part in this chapter, each chapter is a slightly different angle of vision on Bob Dylan. I wanted this chapter to pierce through some of the myths to try to get at as close as I could to what actually happened. But also to try and use it as a way to understand something about Dylan's creative processes during this period of his career in particular. And I was lucky enough actually to get access to some manuscripts of these songs at the Morgan Library which you could see manuscripts of these songs, you could see how he was going from a kind of almost stream of consciousness use of just laying down lines on paper which had no real connection, how he boiled those down into songs. Boiled them down to the point where he was actually working very hard in the studio in Nashville to get them right, get the lyrics right. So you could see this seemingly spontaneous guy actually working very hard at what he was doing and then you could see other aspects on the musical side from the way that he interacted with the Nashville musicians which turns out to have been very, very well.

Jo Reed: His 1966 motorcycle accident in many ways marked the end of that era. What happened?

Sean Wilentz: Well something happened up near Bearsville, New York where his manager had a house. He was riding a motorcycle, something went wrong and it both forced him to slow down, it forced him to withdraw. He had to withdraw for all kinds of reasons but his life was really kind of spinning at the edge. He'd come out of a very long world tour, a very harrowing world tour that ended up with the famous concert in Manchester, England where he got accused of being Judas for being a fan shouted "Judas!" a heckler at his electric music. They were just shocking concerts and he's recorded Blonde On Blonde and he's really out on the edge and I think that he needed to recoup, I think he needed to withdraw for a while to reconfigure, to change shape if you will. But to change shape in a way at a pace that was a little slower and a little less shall we say supercharged than it had been for a couple of years before that. And out of that comes all sorts of new music. He starts recording in West Saugherties with the members of The Band who were also up there getting close to becoming known as The Band. He recorded just for fun a whole string of American folk songs and some originals that later became known as the Basement Tapes. He then comes out while he's basically still doing the Basement Tapes he's putting together an album that will be John Wesley Harding which is his first record after the motorcycle incident which is in terms of its sound, even though he's using some of the same musicians, he went down to Nashville to record it particularly Charlie McCoy and the drummer Kenny Buttrey. The sound is utterly different than Blonde On Blonde. They are very simple, almost Biblical parables, stories, narratives but one can understand them although they certainly have a mysterious quality and have a Biblical quality as well in some of them like "All Along the Watchtower."

(music up and hot)

There must be some way out of here

Said the joker to the thief

There's too much confusion

I can't get no relief

Businessmen, they drink my wine

Plowmen dig my earth

None of them along the line

Know what any of it is worth

No reason to get excited

The thief, he kindly spoke

There are many here among us

Who feel that life is but a joke

But you and I, we've been through that

And this is not our fate

So let us not talk falsely now

The hour is getting late ...

Sean Wilentz: He needed that break in some ways to get his head back together again and to readjust his art.

END OF PART 1.

That was Sean Wilentz in the first of a two-part interview about Bob Dylan. Next time, Sean and I pick up with Dylan's album Blood on the Tracks and the Rolling Thunder Revue.

You've been listening to Art works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam kampe is the musical supervisor

Excerpts from today's songs were all written and performed by Bob Dylan, and used courtesy of SONY Music Entertainment. Each song used by permission of Jeff Rosen and Special Rider Music.

With the exception of "Hoedown" from Rodeo, which was composed by Aaron Copland, conducted by Leonard Bernstein, and performed by NY Philharmonic, from the album, Bernstein: Century Copland, used courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment. Used by permission of Boosey and Hawkes.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. And now you subscribe to Art Works at iTunes Uâjust click on the iTunes link on our podcast page.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Sean Wilentz discusses his biography of 2009 National Medal of Arts recipient Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan in America.