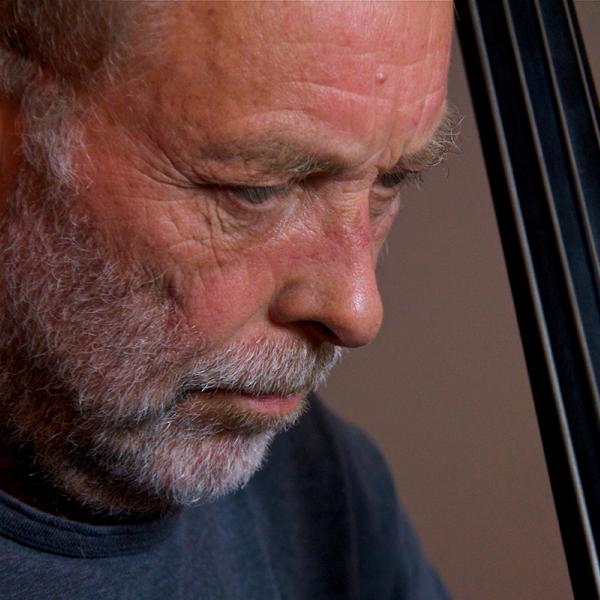

Melissa Walker

Transcript of conversation with Melissa Walker

Melissa Walker: The art therapy is provided to every service member that comes through the NICoE program. It's part of their standard of care, which is huge, because, in a lot of facilities or institutions, it's a complementary alternative. But here it is the norm. And the treatment team has really grasped it as an important piece to understanding person as a whole, we're all about holistic care. So I can attend the treatment team meetings, and we all talk about the cases, and then I can actually show them the artwork. So a lot of times there are things that maybe they hadn't seen -- they couldn't see -- through verbal interaction that is there in the artwork. It's just really been amazing to be a part of this integrated team that really respects and responds to art therapy.

Jo Reed: That was Melissa Walker, she designed and coordinates the Healing Arts program at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

Welcome to Arts Works, the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation's great artists to explore how art works.

I'm your host Josephine Reed.

Because of superb and rapid medical treatment, soldiers who are wounded in combat are surviving more traumatic injuries than previously. And while this is undoubtedly a blessing, it also brings new challenges. We find many of the returning wounded veterans grappling with traumatic brain injuries, or multiple blast injuries, coupled with post traumatic stress.

That's where the National Intrepid Center of Excellence (or NICoE) comes in. It's a four week program for service members suffering from traumatic brain injury, PTSD and other psychological trauma. This state of the art facility on the Walter Reed campus provides an integrated approach to treatment in a holistic, patient-centered environment. Along with psychotherapy and physical therapy, the Healing Arts Program which consists of the visual arts , music, and writing, plays a central role in the assessment and treatment of these veterans.

The National Endowment for the Arts is partnering with NICoE to investigate the impact that arts interventions may have on the psychological and cognitive health of these wounded veterans. In fact, beginning this past January, NICoE has incorporated the NEA's writing program Operation Homecoming into therapeutic sessions with patients and their families.

We're following the progress of the Healing Arts program in all our social media and in our magazine NEA Arts. Later in the summer, there's a special issue of NEA Arts focusing on arts and the military, and I'll be talking to the Operation Homecoming writing instructor, Ron Capps. Today, Melissa Walker is going to give us an overview of the Healing Arts program, focusing on its visual art component. As the program's designer and coordinator as well as its sole visual arts' therapist, Melissa is an enthusiastic and thoughtful guide to the role that art can play in healing.

Melissa begins her four week program with the service members by having them make masks; she closes the program by asking them to create a montage.

When I spoke with her in the art therapy studio at NICoE, the colorful artwork created by the service members lined the walls of the big open space, providing snapshots of the their struggles with wartime memories and the transition to a civilian life.

I began my conversation with Melissa by asking about the service members who come to NICoE. Who were they and how were they selected for this extraordinary program?

Melissa Walker: The service members that are selected to come to NICoE, that are referred to come to NICoE, are normally complicated cases, and that they haven't responded to conventional treatment in the way that they'd hoped to or their providers would hope to. Often it's their primary providers or their home bases that are referring them to the program. They have had either multiple blast injuries or traumatic brain injuries, and they're also dealing with psychological health issues, so it has to be a combination of both, so that's that co-morbidity. They come here and they are exposed to just a vast array of therapies and modalities, alternative medicine, conventional medicine, and they have more sessions with providers in four weeks than they would in years in a conventional outpatient treatment facility.

Jo Reed: You designed the Healing Arts Program at NICoE. What went into your thinking when you created the program?

Melissa Walker: When I first arrived at NICoE, I'd actually just been working at Walter Reed on an inpatient psychiatric unit for a few years, so I had a good idea of what I might be seeing here, some of the psychological health issues, but I knew this would be a little bit of a different population, just because of the co-morbidity, the mix of the traumatic brain injury and the posttraumatic stress, and other underlying psychological issues. So I really wanted to come in with an open mind. I realized rather quickly that while it's was going to be a set amount of time, it was two weeks, we've expanded to four since then, that I would have the opportunity to develop a curriculum, which was rather exciting because I knew that I could really hone in on the modalities that I've seen that have really worked, the directives that I've seen that have really worked. So in order to do that, I decided to meet with each service member individually, and really talk about history, their goals for treatment, and figure out what it is that they're really trying to address while they're here. And one of the main themes that I saw was the search for identity. A lot of them are in transitional phases, due to the fact that they've been injured. It changes what they can do within the military, and they're trying to figure out this new sense of self, this new self they're developing as they heal. So I quickly realized that I needed to do something surrounding identity, and one of the activities that I noticed the inpatient psychiatric patients really picked up on was the mask-making, and I started implementing that as a group for the NICoE service members, and they really, really opened up to it. A lot of different themes presented themselves. I was seeing, after a few months, many of them were trying to process their sense of selves, so when they're deployed they felt like they're one person, and when they return home they feel like they're another. And part of the struggle is, of course, re-integrating back into our society and with their families. So it was interesting to see them trying to really understand the parts of the selves, and do you keep them compartmentalized, and what happens when one spills into the other? And then I was also seeing actual pieces of trauma, memories that they'd seen, that'd been frozen in their minds that they wanted to express and then try to start to understand.

Jo Reed: And we're talking about a mask that one would put over one's face?

Melissa Walker: One of the writing instructors here actually likes to say that there's something very interesting about a mask because it can both hide part of your identity, and it also, in this case, it expresses part of the identity. And when I go to introduce them to the directive, I actually say, "Focus on who you are and what it is that you want to express about yourselves. Don't worry so much about the product. It's all about the process. And what you put into it of yourself, your personal stories will make that work rich." And that normally leads them to feel pretty safe to create. It's literally kind of symbolic for themselves, in a sense, it's externalized, it's their own face, it's their own self, that they can then process, they look at, visualize, hold in their hands, and begin to talk about. I think that really helps start to piece together what it is that they're dealing with, what they've seen, what they're going be like moving forward. So it's very interesting, I've had a few service members say there's something so different about the art therapy, because when you are trying to talk about what it is you just created, part of the pressure of describing a horrific moment they remember, or parts of themselves that they're ashamed of, that pressure is alleviated a little bit because everyone's staring at the creation and not right at them. It's a two-way street, really, here. We're into integrated care, but they can then go and talk with the psychiatrists, the psychologists, about what it is that they just created. And sometimes they'll even come up here, the other providers. They'll look at the work and they'll start to process with the patient. Sometimes the service members will open up about things they haven't before with those providers, and then they'll come here and they need to express what it is they just talked about. I see that, too, within the different arts modalities, the different types of creative arts that we provide here.

Jo Reed: Because you provide visual arts, music--

Melissa Walker: The visual arts.

Jo Reed: And writing.

Melissa Walker: Music and-- yes, and creative writing. I've had service members say, "Once I started writing, then I felt safe creating the art." I've had service members say, "The art really got me, you know, wanting to write, because once I started to express all that, I realized I had a story to tell. I had things that I wanted to express, that I wanted everyone to know about, and that felt good, kind of getting off of my chest." And it's the same with the music, and, you know, some things aren't for everybody. But the nice thing is, is normally, of those three creative arts options that we can give them here, they can connect with at least one, if not all.

Jo Reed: What are some of the unique needs that service members who come here have?

Melissa Walker: It ranges, of course, case to case, but the main needs that I see, it's really, the ability to focus. They really want to be able to focus, and their memories aren't the same. And there's the isolation piece of posttraumatic stress, the hyper-vigilance and inability to trust. So one of the things that we're really focused on here is building that community, and helping them know that there is there is support out there, and there are people they can trust with what they've been through. I think many of them feel like they can't open up, because they'll either be judged or they won't understand. And what's lovely about being here is that when you're in a group, specifically for me, what I've seen in the art therapy groups, they'll open up about something, and they're surrounded by their peers, and their peers understand, and they're nodding their heads, and they are really validating what that person has been through. This comes up a lot, and it's a big theme for me, but this need to express themselves, to tell their stories, it's there, and I think we're giving them many different ways to go about that, and it's, as I said, validating, and it's important. It's important for us to know what they've been through, and they don't need to be ashamed.

Jo Reed: I know you have done a great deal of research about how art really helps with healing. Talk a little bit about what you've seen, with the research that went into this.

Melissa Walker: Some of the most interesting research I've seen is the way that the brain works when you're working with the arts. Those who have been traumatized often have a hard time verbalizing what they've been through, because neuroimaging scans have shown that the Broca's area of the brain, which is the speech area of the brain, shuts down when individuals try to recount a trauma. However, the part of the brain that encodes the trauma, the sensory kind of aspects of that-- sight, sounds, smell, feel-- that's the part that lights up, and it's the same part of the brain that you utilize when you're creating art. What's interesting is once. I believe once you create the art, you're utilizing parts of the brain that you don't normally, maybe, or that are accessing those traumas. And then you then verbalize what it is that you were trying to express, that you're then reintegrating the brain, which is how a healthy brain works. The left and right hemispheres communicate with each other. So, scientifically, that's what I believe is happening, and we're looking into how to really see that for ourselves here at the NICoE.

Jo Reed: Well, Melissa, since your therapeutic area is visual arts, I want to focus on that. We talked about masks and how you use them in therapy. Another technique you use is montage. Explain what that is and explain how you use it.

Melissa Walker: I love the idea of the montage. The montage is literally the collaging of different elements of art. So they'll have magazine clippings, they can use clay, they can use buttons, they have everything. Anything that they can get their hands on they're allowed to use in these images, and they really convey very powerful messages. And I love how symbolically the layering of all of these elements-- it's very much like how they come to us. They are layers and layers of complications. I mean, our service members, they have so many different aspects to themselves, they have so many different stressors that many of us may never understand, so, symbolically, they're able to collage and show this through the montage. So montage painting, I felt, would be important to introduce in the third or fourth week that they're here, because they have so much happening, and I think, as they come and they're telling their stories, and the waters clear a little bit, and they start to grasp where it is that they're headed next, and they start to feel a little better, I wanted to give them the opportunity to really focus on how the process is going for them: the NICoE experience, and in more general terms-- past, present, hope for the future. And in many of these montage paintings, what's so great is they can express that there's hope. So we see many montage paintings go from a chaotic past, and then what happened while they were here, as they heal, and a hopeful future. I think that's important, too, to remember to focus on, "I can be better"-- have positive thoughts about the future - it's nice to give them that opportunity.

Jo Reed: When the service members first come, how do they initially respond to the idea of art therapy?

Melissa Walker: I must admit, and I am so used to it, so it never hurts my feelings. At this point, I know the process so well, and I trust it so well, that it does not even affect me, but there are so many smirks in the room

Jo Reed: And rolling eyes?

Melissa Walker: From the moment they sit down for the first session, and I get it. I mean, these are warriors. I just don't think people -- I don't think they even visualize themselves sitting in their uniforms painting, or using clay, or creating a mask. But it's all about how it's presented to them. They're surrounded by beautiful work of their peers. It's so powerful, and I think many of them can connect with the message that the work conveys. And I make sure to tell them that this is just about exploration, and not like your typical art class, where you're going be critiqued or graded, and that it's a judge-free environment for them to just express themselves in a different way than they have before. And, you know, I say, "I know you've been telling your stories over and over to the doctors, and here is just a different way you can tell your story, utilizing, a nonverbal modality." And really, I tell them, "Don't focus on the product or the aesthetic quality of how it looks at the end. Focus on investing yourself into the piece, and that's what'll make it rich." And it's amazing. Every single time - they'll sit for a moment and think about it, and next thing you know, they're in it. They are in the process, and they will sit there for two hours. And afterwards, they'll just be surprised. They'll say, "Wow. I mean, I get it now." Then they'll come back for more, and it is very, very rare that I encounter a service member that won't create art.

Jo Reed: What do you think it is about art that allows for that kind of healing and that kind of expression?

Melissa Walker: I honestly think it's a mixture of things. It's the material itself is alluring, and you have complete control over what you want to create. You have control over that memory, for once, and I think that's very powerful. And then the actual visualization of something, and then the execution of it, and overcoming something that may be a challenge at first, just, I think, allows them a sense of confidence and mastery that they maybe are not getting in other aspects of their lives at this time. And I think at the same time, I mean, it's art, you're using everything. I mean, you're using your hand and eye coordination, your motor skills, you're using different parts of your brain that you maybe don't normally exercise, and it's nonverbal, and I think that they feel safe. I think it's this concrete piece of themselves that they can talk about. They can understand themselves better, and then explain.

Jo Reed: What first drew you to art therapy?

Melissa Walker: I was an artist growing up, so I just, completely for myself, understood the power of the use of art in understanding myself, instilling confidence, and having something that I could call my own. I went to undergrad for art education, but I always had an interest in psychology, I had a minor in psych. And when I went to teach, I realized there's something more to this. I have the utmost respect for teachers, but I realized I wanted to be able to get to know each student better than I could in that scenario. So I continued on, I got my master's in art therapy at New York University, and it was this wonderful mix of psychotherapy and theory and art, and it was just -- I loved it. It was perfect. And while I was in grad school, I was an intern at Bellevue Hospital on an inpatient unit, and I knew that I-

Jo Reed: In New York City?

Melissa Walker: Yes, in New York City. And I realized that I really did have a love for trauma and psychiatry and psychology. So I decided that's where I want to go. I want to do something with that. I don't know where it will be, I'll move if I have to. And up came this announcement for Walter Reed, and I looked at it and said, "That's exactly what I need to do." And it was interesting because I have military history in my family, and my grandfather both are veterans. And my father was also a corpsman. So, I had military history, but the most important piece of that history was that my mother's father was wounded in the Korean War, and I believe I grew up around somebody who was dealing with posttraumatic stress. So for me, it was very interesting to kind of connect, like, "This is the effect that war has on somebody," and, it's sad because we didn't really have the same name for it then, and the treatments that we do now, and, , they had, of course, different names for it-- shellshock, a thousand-mile stare, but I think that left an impression on me, and so I was always very interested, and I just kind of gravitated towards the education of trauma, and understanding how to treat it. So it came full circle.

Jo Reed: It sure did. How long have you been working with the military now?

Melissa Walker: I started working for the DoD in 2008, so I'm coming up on four years, and it's just been humbling. I'm so honored to have worked with this population. They're special, they really are.

Jo Reed: We have seen research about the benefits of creative therapies as part of treatment plans. Can you just talk a little bit about how the art therapy is integrated into their treatment.

Melissa Walker: I'm very fortunate to be working among colleagues that believe in the power of art therapy, and have actually, it is implemented, and it is integrated into the treatment team. It's been so interesting, because we all talk to each other. We communicate about each case, each service member, and I'm actually able to use the art itself, and show them, the providers, what the service member created, and talk about the symbolism that he or she wanted to depict, and it helps the treatment teams gain a whole picture of the person. So a lot of times, there are things that maybe they hadn't  seen -- they couldn't see -- through verbal interaction that is there in the artwork. I think that they're very accepting of this as an alternative medicine and psychotherapy. And service members are opening up about things that they hadn't before, and I think that's huge. And helping instill hope for things that they're capable of, that they can overcome challenges, that they can move forward.

Jo Reed: What makes you feel very successful here? Or "satisfied." That's probably a better word.

Melissa Walker: I'm most satisfied-- I'm probably what kind of keeps me going are the, as I like to call them, and I think many art therapists before me like to call this moment, it's the "aha moment," and that's when a service member really just, they look at what they've done, and all the pieces fall into place, and then they express what they've done, and they say, "I can't believe I just said that," or "That was so enjoyable." "That was really relaxing," or, "I really get this." This moment of - it just really connects, and it's art. It's so neat to me to watch it work. And I talked about really trusting the process, but it's incredible. And I think it's just amazing when they connect with it in such a way that they say, "This is the thing. This is what helped me." One service member said, "This was the key. This was everything that was bothering me in one place, finally, and I could talk about it." And he took his mask with him and shared it with his psychologist post-discharge, I think in every session for quite a while, just to continue to talk about what it meant to him. So to have that much weight and importance and personal meaning put into something that they've created is powerful and special, and that's when I'm satisfied: they get it.

Jo Reed: What's surprised you in your work?

Melissa Walker: Oh, gosh, everything. With this population, specifically, I was so surprised by their openness and their willingness and their bravery to dive in to the arts, which is, many times, something that they had never really explored before. So that was a wonderful surprise, to see them hungry for this, and then really respond. All the time, I'll sit in a group, and I'll look around, and I'll see all the service members focused on their work, and I just can't help but think... sometimes it's just like... I don't know how I can put this. I mean, it works. Oh, my gosh! This thing that I loved and studied and wanted to share is working. They're really responding to it. They really love it, and for me, it was not so much a surprise, because, as my intuition said, "This is what I need to do, and this is what people need, and I need to be an advocate for this, and help people feel safe to try it."  But the fact that, you know, you look around and you see it, and I have these moments where it's just never gets old.  Every new piece of work is a surprise.

Jo Reed: Melissa Walker, thank you. Really, thank you.

Melissa Walker: Thank you.

Jo Reed: And thank you for the fantastic work that you do.

Melissa Walker: Thank you very much.

Jo Reed: It's my pleasure. Thank you.

That was Melissa Walker. She coordinates the Healing Arts Program at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence (or NICoE) at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

You've been listening to Artworks produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor.

Excerpts from Mabel Kelly from the CD "Morning Aire," performed by Sue Richards used courtesy of Maggie's Music

Original guitar music composed and performed  by Jorge F. Hernandez.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. And now you subscribe to Art Works at iTunes U -- just click on the iTunes link on our podcast page.

Next week, filmmaker Na'alehu Anthony.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter.

For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Melissa Walker discusses healing wounded service members through art at Walter Reed.