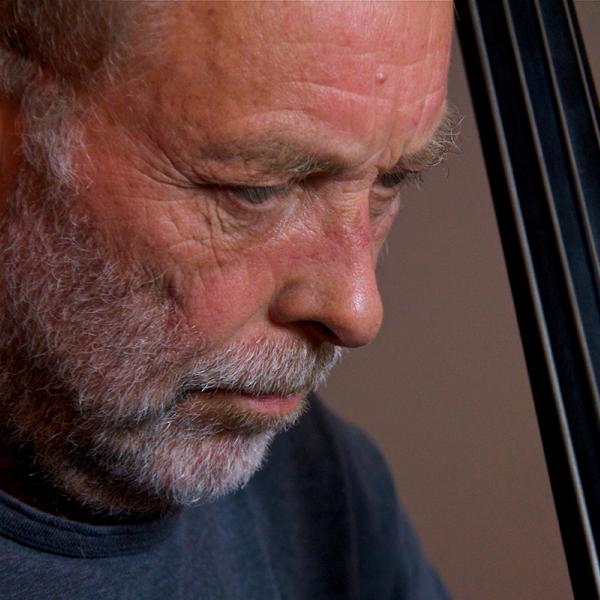

Margot Livesey

Margot Livesey: While paying homage to "Jane Eyre," and wanting in some ways to reimagine that wonderful novel, I was very eager to write a novel that could be read both by people who had read "Jane Eyre" and by the many people who have not read that novel. So I was concerned to include both kinds of readers. I didn't want to irritate the Bronte fans, but I also didn't want to exclude those people who for whom Charlotte Bronte was not in their pantheon.

Jo Reed: That was author Margot Livesey talking about her latest novel, The Flight Of Gemma Hardy. She'll be reading from it this Saturday at the National Book Festival.

Welcome to Art Works, the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation's great artists to explore how Art Works. I'm your host Josephine Reed.

This week, Washington DC is getting ready for the annual National Book Festival when thousands of book-lovers come to the mall to listen to and converse with hundreds of others. The NEA is one of the sponsors of this literary celebration. Our Poetry and Prose Pavillion will host a small fraction of the authors who have received NEA fellowships over the course of their careers. Among the authors reading in our tent this are Junot Diaz, Tayari Jones, Philip Levine and Margot Livesey.

Margot Livesey is a critically acclaimed and inventive writer. The recipient of grants from the Guggenheim Foundation as well as the NEA, Margot is the author of seven novels including Homework, Banishing Verona, Eva Moves the Furniture, and most recently, The Flight of Gemma Hardy. As you just heard Margot explain, Gemma Hardy is her homage to Jane Eyre set in mid-twentieth century Scotland. It's a story that in the beginning closely mirrors Charlotte Bronte classic novel. It tells of the misfortunes of an orphaned girl who suffers at the hands of her cruel aunt and uncaring cousins, who's sent to a boarding school where as a working student, she's expected to earn her keep and who eventually finds unlikely romance with a mysterious employer on a remote estate. I began reading the book with a little bit of trepidation. Like most other girls who read, "Jane Eyre" was an important part of my reading life as a kid and I wasn't sure why a 20th century version of it was necessary. But fairly early on The Flight of Gemma Hardy and Jane Eyre diverge and Gemma becomes absolutely a heroine unto herself and it's her story that unfolds so vividly. I was lucky enough to speak with Margot Livesey and began by asking her the obvious question about The Flight of Gemma Hardy.

Jo Reed: Why did you decide to reimagine "Jane Eyre" in a 20th Century setting?

Margot Livesey: Besides having entered into some sort of peculiar mental state, you know, some peculiar hallucinatory state, I think part of the reason was, as you just said, Jo, I mean, "Jane Eyre" was one of the first chapter books I read as a child, I completely identified with Jane, even though I didn't understand lots of what was happening, I loved it, I entered into it so fully, and certain scenes in the novel, I'd have to say, are more real to me than events in my own life, I can remember more accurately, Rochester falling off his horse on the ice at Jane's feet, than I can remember a party I went to when I was 18, say. But I had never thought for a moment of trying to reimagine "Jane Eyre", until I went to a book club here in Boston, and the room was filled with passionate readers who had all read "Jane Eyre." Many of the people in the room had read "Jane Eyre" several times. And we had such a wonderful lively discussion about the novel, and part of the discussion was about, why does this novel, after 150 years, still speak to us so passionately and reach so many readers, and stay with readers long after they've closed the book, which is not true of lots of other books that we love while we're reading them. And I drove home that night, thinking about Charlotte Bronte's amazing accomplishment, and how she brings together in "Jane Eyre" what I would say are two of our great archetypes: the pilgrim, Jane going out into the world to find herself, and her fortune; and the orphan, which is also, I think, in some mysterious way, one of our great archetypes. I mean, so many beloved books are about orphans. And in the days after this book club, I found myself sort of making notes and thinking about it, an thinking about Bronte's great question, you know, how is a young girl, a young woman of no means and no family as far as she knows, going to find her way in the world. And it still seemed to me, a really interesting and a really pressing question. And with that thought in mind, I thought, well when-- if I was going to ask the question again, when would I set the novel. And at first I thought about setting it, you know, much closer to the present, but when I stood back and tried to put my, sort of novelist's hat on, rather than my reader's hat, I thought that it would be particularly appropriate to set it in the 1960s, just before that great wave of feminism broke over both Europe and America.

Jo Reed: And why then?

Margot Livesey: Well I liked the idea that the reader would know, even though Gemma does not, that she is growing up into a time of many more possibilities for women. When I was growing up in 1960s Scotland, you know, middle class women really, there were really three professions open to them. They could be a nurse or a teacher, or a wife. And once you became a wife, you very typically gave up the first two. And all of that was just going to be so radically overturned by the mid-70s, for many, many women. And I also recognized that part of the enduring appeal of "Jane Eyre" is the way in which Charlotte Bronte very skillfully stole from her own life, and I thought, well if I set the novel in a period that I had lived through, when roughly the same age as my heroine, then I could steal as well, and that might be a way of getting some small part of what Bronte accomplishes into my own book.

Jo Reed: The Flight of Gemma Hardy opens with Gemma, who is an orphan, and her mother was Scottish, her father was Icelandic, and she was living in Iceland, and her uncle, her mother's brother comes to Iceland and brings her back to Scotland. And we first meet her when she's ten, and her uncle who had been very, very kind, has died very suddenly, very tragically. What happens then?

Margot Livesey: Well, as long as Gemma's uncle is alive, she finds herself a beloved member of his family. He has three children with his wife, and Gemma's three cousins are quite kind to her, and his wife, her aunt, is-- at least behaves tolerably, if not always warmly towards Gemma. But when her uncle dies, she suddenly realizes that she isn't an insider in this family, she, even after seven years, is still an outsider, and that really becomes painfully apparent.

Jo Reed: A kindly doctor who thinks he is doing a good thing, recommends that Gemma be sent to a boarding school, because he sees that she is a very smart girl, but a deeply unhappy one. And Gemma, at first, has great, great hopes for that boarding school, but things don't quite turn out the way she had hoped.

Margot Livesey: Yes. Throughout Gemma's journey, if you will, a number of people sort of step in offering advice or counseling or thinking they know what will be best for her, and this kindly doctor is the first of these people to intervene, as it were. And he's right, in a sense, that education is the best possible escape for Gemma, but unfortunately picks the worst possible institution for her, a school called Claypoole School, which, I'm afraid, is a reimagining, with much exaggeration, of a very difficult girls school that I myself went to in the borders of Scotland.

Jo Reed: Well yes, you do say in a note that you steal from your own life. Is this one of the ways that you did, when you described that school?

Margot Livesey: I did very flagrantly, Jo, and when I went back to do research, and to make sure that I just got all the details of the school buildings correct, I discovered that it has been razed to the ground, so I'm afraid that shamelessly licensed me to imagine wildly.

Jo Reed: Well, I found this so interesting, Margot, because in the beginning, I thought the entire arc of the novel was resembling "Jane Eyre" very closely, down to the opening on the rainy day, sitting in the window seat, reading a book about birds, etcetera, etcetera. But at a certain point, something happens and you created a character who might be very much like Jane Eyre, but who absolutely became herself. And I'm still not sure how you did that.

Margot Livesey: I love that you say that, Jo, and it's a perfect way to describe what I hoped I was accomplishing. I knew, even as I sat down to start this preposterous undertaking, that I was not trying to do what, for instance, Jane Smiley did in "A Thousand Acres." I was not going to try to, in "A Thousand Acres," Smiley transports really every scene of "King Lear," to a farm in Iowa, and I knew that I had no interest in even attempting to do that for "Jane Eyre." So I was trying to signal to the reader, really from the opening pages that, on the one hand, I was paying homage to this beloved novel, but on the other, that Gemma would be very much her own person, her own heroine. And that was one part of the reason why I gave her her Icelandic heritage, to plant the idea that she was going to make her own journey in the reader's mind.

Jo Reed: And why Iceland of all places?

Margot Livesey: You know, I auditioned various countries, as a possible place for Gemma's father, and I thought-- I had several things in mind. Iceland used to be part of the old Viking empire, along with Scotland, so there's-- there have long been links between Scotland and Iceland. I wanted to pick a country that was small enough, that you could actually hope to find your ancestors if you decided to do so, and because the population of Iceland is still only a little over 300,000 people, and they keep very good records, people there are actually very aware of their lineage, and so for that part of my plot, which I don't entirely want to give away on the air, I thought a small romantic country was a good choice for Gemma.

Jo Reed: And I just would like to return to the school, to Claypoole, and what happens to her there, because she is there as a working girl, and we see class issues that really, it's a strand throughout "The Flight of Gemma Hardy" I think.

Margot Livesey: Absolutely. I mean, class is very much at the heart of Gemma's life and of her difficulties. As it was, I think for Jane Eyre, and as I think many British writers have shown on the page. I think that the idea of the working girls, you know, I mean, the idea of the working girls comes very much from my imagination, but it was the case that at this quite posh boarding school for one week every term, we had to help with housework and chores. And it was the case that many of the girls were quite wealthy and, to my mind, quite stupid, or at least, perhaps I should say, they didn't exert themselves intellectually. And on the third hand, it was also the case that the school was very much a sort of kingdom to itself. There was a high wall round the school grounds, no school inspectors ever visited during my four years, and parents visited very seldom. And of course people didn't use the telephone casually, so it really was very much a world unto itself, although not nearly as savage a world as I portray.

Jo Reed: Did you read a lot, the way that both Gemma and Jane did?

Margot Livesey: I did. The library was my favorite room in the school. It was a very beautiful oak paneled room with shelves and shelves of books that no one else seemed to pay much attention to.

Jo Reed: Gemma ends up as an au pair in the Orkney Islands. Tell us about the Orkneys and what she finds there.

Margot Livesey: I'm going to answer the question in a slightly sideways fashion. One of the things that I really admired about "Jane Eyre", is the way that Bronte has five very distinct locations and five very distinct settings and I decided, even as I was making Gemma into her own character, that I would use that structure. So I tried to find places in Scotland that I know and love, and the Orkney Islands are one of my favorite places, very romantic place, a place in which one is very aware of the layers of history, and at the same time, especially in the 1960s and '70s, a very isolated place. So again, I thought that that could do a lot atmospherically for my novel, and make certain things possible in Gemma's life.

Margot Livesey: Yes. Taming Nell is quite a struggle for Gemma, and I think, forces her to become an adult. I mean, as a schoolgirl, she's been very much a child, but suddenly, being in charge of another person, an eight year old girl, she has to become, in many respects, a grownup, and it accelerates her journey towards adulthood.

Jo Reed: Then she meets her own Mr. Rochester, the master of her house, Hugh Sinclair. Tell us about him.

Margot Livesey: Ah, Hugh Sinclair. One of my resolutions when I embarked on "The Flight of Gemma Hardy" was that there would be no attics in my novel, that I wasn't going to have an attic with a mad former wife, with Mrs. Rochester. But, at the same time, I couldn't reimagine "Jane Eyre" without having a Mr. Rochester-like figure. So Hugh Sinclair is my attempt at filling those very large charismatic, and I think quite complicated shoes. I think most young readers are swept up by Mr. Rochester, and fall under his spell, as Jane does, but then, I think, when we read "Jane Eyre" when we're older, we actually think he's often quite unkind to her, and teases her in quite a mean way. So trying to create a man who seemed to have some of Rochester's charisma and power and charm, while also trying to make him a person that wouldn't rage my own feminist sensibilities, never mind those of my friends, was quite a challenge.

Jo Reed: There are so many complications, again, there's a complication of class. She works for him. But then that's also compounded by age, he's more than double her age. And then the other disparity in gender at that time.

Margot Livesey: Yes, and all three, I think, play an absolutely crucial role. My own reading of my own novel is that you know, the first attempt at marriage, and I don't think I'm giving anything away in saying this, you know, has to fail, because really, Gemma is too unequal to Hugh Sinclair, they could never have a really good union when she is so far from being the independent being she aspires to be.

Jo Reed: Yes, exactly, and because of a lie that she simply cannot bear, she separates herself from Hugh, and begins another flight in which she does come into her own more, after great difficulty.

Margot Livesey: Yes. She has to confront many dragons and demons in the second part of her journey. And I should say that one of my ambitions for Gemma was that she should be not just a character, but a heroine. I really wanted her to have something of that heroic, I don't know, "Tess of the D'Urbervilles," stature, if you will, and so for me, part of being a heroine is that you do have to confront terrible difficulties and ordeals.

Jo Reed: Are you drawn to literary gambles? And I'm thinking of, "Eva Moves the Furniture," there are a couple of ghostly characters in that, and clearly in this book, that was a gamble.

Margot Livesey: You know, one part of me wants to say no, no, I'm an extremely cautious and conservative writer. But I think that when I'm actually at my desk, my imagination does run very freely, and certainly in "Eva Moves the Furniture," which is a kind of love song to my mother, and probably my most Scottish novel, alongside Gemma, I really felt that writing about the supernatural and about my character Eva's relationship with the supernatural was an essential part of the book. But it also did bring me up against the fact that writing about the supernatural is an extremely tricky thing to do in traditional white Anglo-Saxon fiction.

Jo Reed: Mm-hmm, definitely. I want to go back to Gemma, coming into her own, not just in the life of the book, but in the life of my mind, as I was reading this book. And for those of us who love reading, those characters become more real, often, than the people I work with, as we mentioned earlier. How do you do Margot go about creating a character?

Margot Livesey: Gosh, if only I had a really good answer for that question, I would spend much less time revising than I presently do. I grew up, as you've probably guessed, reading the great 19th Century novels, because they were what my father's bookshelves had to offer. And many of those characters made an indelible impression on me, and when I began to write my own fiction, I was always trying to find-- figure out, well how is that done in terms of craft, how do you create a character who walks off the page into the reader's imagination, and then stays there, takes up residence there in this mysterious way. And I think that you know, for me, one of the rules in creating my characters, at the moment, it might change, is that every character has to have something that they share with me, although the reader may not always realize what that is, and also something that they absolutely do not share with me, some area of their life or experience in which I can let my imagination run wild. But quite-- I still think there's something ineffable about quite how one does this.

Jo Reed: When did you start writing?

Margot Livesey: Well I did write as a child growing up in the Scottish countryside, with not very many forms of entertainment. Reading and writing played a big role in my life, especially in winter when I couldn't go out and chase the sheep, and build dams and huts. And then I went to university where I wrote many critical essays about, "Pamela," and "Middlemarch," but nothing creative. Creative writing was not taught at that time. And then the year after I left university, I went travelling with my boyfriend of the time round Europe and North Africa, and he was writing a book, a book in philosophy of science. And at a certain point, maybe October. We set out in September, maybe I lasted four or five weeks, I began to realize that I wasn't that happy going to explore cathedrals and marketplaces on my own while he sat in a campsite and worked on his book. And I decided I would try to write a book of my own. Because I didn't have a subject matter, I mean, I wasn't going to write a history of the Alhambra, or a guide to ice skating, I decided to write a novel. I'd been reading novels since I was five years old, if you count, "Little Red Riding Hood," so…

Jo Reed: I do.

Margot Livesey: I thought, gosh, I've been reading novels for 17 years, surely I know how to write one. And unfortunately that turned out not to be true.

Jo Reed: And how did you discover that turned out not to be true?

Margot Livesey: Because in June of our year of traveling, I sat down to reread the pages I had written, Jo, and they were bad in almost every way you can imagine, and probably some you can't. They were simultaneously boring and preposterous, the descriptions read like they'd come from guidebooks, the characters talked not like anyone in books, but not like anyone in real life either. They talked sort of like, I don't know, Nazi zombies or something. Very stiffly, very stiffly. Just everything about the book felt lifeless. There was no life on the page. But when I got to the end of this very painful reading, I did realize that I was actually profoundly interested in getting better at this mysterious thing called writing fiction, and I was just intensely interested in the fact that I had completely failed to be influenced by my 17 years of reading. And I thought, how could I get to be more influenced by the books that I love?

Jo Reed: And what was the answer?

Margot Livesey: For me, the answer was to, as Francine Prose says in her wonderful book, "Reading like a Writer," for me, the answer was to stop doing the thing I did when I read, which was to fall through a kind of trap door into the world of the novel, and to start trying to read as a writer, to struggle back out through that trap door, and think, now wait a minute, how did she do that, how did she make it so interesting, when Molly came into the room?

Jo Reed: And how did that affect you as a reader?

Margot Livesey: Well it remains a struggle for me to read as a writer, because I still read omnivorously, and you know, very much giving myself over to the books that I read. I mean, for me, that's the huge pleasure of reading. But I have learned, you know, as I embark on different projects, I go and look at books that I think will feed that project in different ways, and just study even a few pages to see what the author is doing at the level of the sentence, the phrase, the paragraph. I should say, however, that once I embarked on writing The Flight of Gemma Hardy, I never once went back and looked at "Jane Eyre" and indeed, only recently found my copy of the book, because I'd hidden it so well.

Jo Reed: And have you reread it since Gemma?

Margot Livesey: You know, I haven't dared to, Jo. I think I might not be able to talk to you on the radio today if I reread "Jane Eyre."

Jo Reed: Well your book certainly had made me want to reread "Jane Eyre" as well as go to the Orkneys and Iceland.

Margot Livesey: Oh good, I mean, all destinations that I completely recommend. I'm thinking that there ought to be a sort of Gemma Hardy tour.

Jo Reed: I think that would be lovely. Sign me up for it. Now Margot, I know you also received an NEA grant. At what point in your career did that happen?

Margot Livesey: That came at a wonderful point in my career. I had published a collection of stories, and you know, was really working very hard on stories, having decided that, after my terrible first novel, that it would be better to make mistakes in 25 pages, than 250 pages. And I applied for the NEA, because someone had told me I was eligible, and I put some stories in an envelope and sent them out and really, truly did forget about them until this wonderful announcement came, and what that gave me was a year off from teaching, which was wonderful, and also, of course that incredibly valuable gift of someone saying, we believe in you, keep going, which was perhaps the best part of all. And with the help of that grant, I was able to write a somewhat better first novel, a novel that went on to be published.

Jo Reed: And what book was that?

Margot Livesey: It was a novel called, "Homework," about a young woman who finds herself embroiled with a very difficult step-daughter.

Jo Reed: It seems to me that if one doesn't-- isn't lucky enough to have a university job, it's very hard to make a living as a writer.

Margot Livesey: I really think that that's the case. And I feel deeply fortunate to have institutional support, because I don't think I would be very successful if I had to do the kind of journalism that many writers do manage to do, to support their literary work, or if I, alternatively was writing novels, very much to a deadline. At the same time, I very much admire people who do those kind of-- that kind of writing, and work in that kind of way.

Jo Reed: For any artist, it's always a struggle without institutional support, I think.

Margot Livesey: Yeah, I mean, we need some kind of patronage, hence the wonderful NEA, hence universities, hence, in my case, for many years, waitressing. I really ought to acknowledge all the restaurants who helped to support my early stories unwittingly.

Jo Reed: You're also known as someone, Margot, who works with new writers. You donate time and energy to Grub Street, which is an independent writing center. How did you get involved with that?

Margot Livesey: A couple of my former students founded Grub Street years ago, students who had worked with me in the Boston University writing program. Eve Bridburg, and Julie Rold and a couple of other people. And I thought from the start, what a wonderful thing this was for writers in the Boston area. I myself never had the good fortune to do an MFA. I'm very much an autodidact, and an autodidact who taught herself painfully slowly. So I've really come to envy my students at Emerson College, who, you know, in six weeks, learn what it took me sometimes six months or even six years to learn. At the same time, I don't think an MFA is the only way to study writing, and Grub Street provides wonderful classes, and also wonderful community for young writers.

Jo Reed: Tell me what you're working on.

Margot Livesey: I'm trying to do something that strikes me as almost more preposterous than trying write a reimagining of "Jane Eyre". I'm trying, in my eighth novel, to write a novel set in New England, where I have lived on and off since 1983. In my previous seven novels, characters have sometimes visited America, and once or twice I've had Americans make brief appearances in my pages, but I've never written anything that was really set here. So I'm finally trying to do that, and I find it both exhilarating and terrifying, and of course I should say that my American friends are mostly vehemently opposed to the project, as they worry that they will become material, and I think they're right to worry, because of course who am I going to study if not my friends?

Jo Reed: But why is it daunting, Margot, if you've lived here for almost 30 years?

Margot Livesey: I wonder about that, Jo. I think it's partly that--I think a tremendous amount of our-- of what fills our writerly banks, if you will, that comes to us in childhood, during that very impressionable plastic period of our lives. So much-- we learn so much about the world around us, the people around us, our experiences are so rich and so densely textured. So I think missing that relationship with America has always made me cautious, and I have to say that most British writers who have written novels set in the states, have chosen the route of satire, and I am absolutely not interested in writing a satire. I don't have the gift for that. So trying to find my way into an American sensibility and an American language and an American past, if you will, is a challenge, despite all my time here, and my many close ties to this-- particularly to this part of America.

Jo Reed: Well I look forward to it whenever it comes out, Margot. So thank you, Margot, thank you for giving me the pleasure of your book.

Margot Livesey: Thank you so much, Jo. You say exactly what I hoped a reader would say.

Margot Livesey: Thank you so much, Jo. You say exactly what I hoped a reader would say.

That was novelist and NEA literature fellow Margot Livesey. You can hear read her read from and discuss her novel The Flight of Gemma Hardy this Saturday in the poetry and prose pavilion at the national Book Festival.

You’ve been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor.

Excerpt from the “Didda Fly and Dodger” from the album Lost in the Loop performed by Liz Carroll used courtesy of Compass Records Group. You can subscribe to Art Works at iTunes U -- just click on the iTunes link on our podcast page.

Author Margot Livesey discusses The Flight of Gemma Hardy -- her reimagining of Jane Eyre. [32:40]