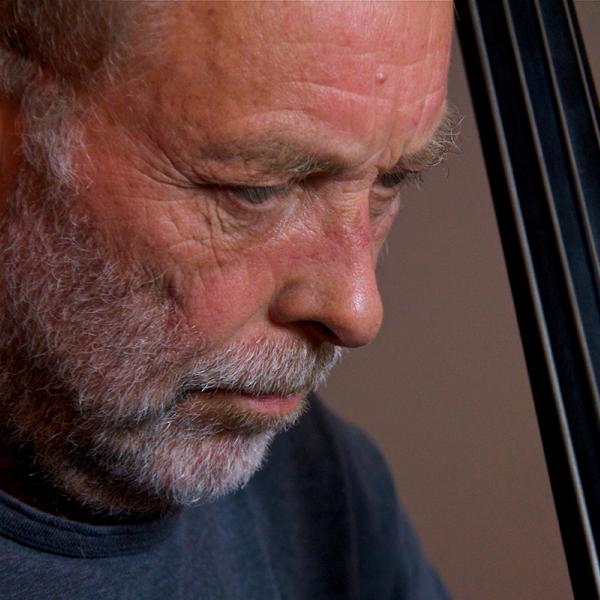

Jonathan Tucker

Music Excerpts: "Twararutushye," composed and performed by Samputu

from the cd, Celebrating LEAF, 2005

Transcript: Jonathan Tucker

All I know is wind

During its inconsiderate visits

My organs tremble like dust

A hollow chorus of vibrato

Whistling its way through my insides

Intrusive and always unwelcomed

All that I know is plantation

Meticulous murder scene stretched

Noble and wide

A cotton-colored grin bent

Against southern sky

Birds with feathers made of ash

Beating against humid air

They flutter like frightened brown children

At the crack of daddy's leather

All that I know is this existence

Hung loosely on a rusten wire

Crossed toward all the feather flapping mouths

Above my head meant to make pale cheeks stretch

For amused smiles

All I know is this land

All the crime it done committed

The blood it swallows

The vegetation it vomits

All that grows from this ground tastes like black hands

All I know is sunset

The sons of the sun are simply silhouettes

Breaking the path of an evening breeze

Lifeless pendulum swaying in a grave

Six feet of oxygen dug from midday sky

Skin moaning against the weight of death

They don't really need me

When there are things far more frightening

Being hung in these fields

Not sure if I'm protecting the crops or the carcasses

Because I can't seem to scare these birds past

The stench of lynched flesh

Wrapped in obsidian skin

All that we know is wind

Music Up

Jo Reed: That is Thomas Hill performing his poem, "Scarecrow," at an international youth poetry slam. Thomas is the current DC Youth Slam Champion and this is Art Works, the weekly podcast produced by the National Endowment for the Arts. I'm Josephine Reed.

The National Book Festival takes places on Saturday August 30 and once again the NEA is sponsoring the Poetry and Prose Pavilion. This year's authors include Billy Collins, Paul Auster, and Elizabeth McCracken, and we're also adding something new. We asked the District of Columbia’s top youth slam groups -- the DC Youth Slam Team and Louder Than a Bomb DMV -- to participate in a poetry slam. Champion delegates from both groups will perform new poems on the subject of books and reading, and one of them will be named the city’s top youth slammer.

Poetry slams are credited for reinvigorating poetry, and bringing it out of the classroom and into the street. Young people in particular have taken to slam poetry, in part because it encourages experimentation with content, style, and delivery. You can trace the growth of its popularity through the ever-increasing competitions, ranging from the local to global. One of the most dynamic festivals is Brave New Voices --the only international youth poetry slam. The winners of this year's Brave New Voices Festival? That same DC Youth Slam Team that will be performing at the book festival. What follows are excerpts from poems the team performed in both the 2013 and 2014 Brave New Voices festivals, and a conversation with the team's coordinator Jonathan Tucker. Here's Jonathan Tucker -- giving us some of the basics of slam poetry.

Jonathan Tucker: A poetry slam is a competition where the competitors use their poems to compete and they’re judged by five random people chosen from the audience who do not know any of the competitors and might not know anything about poetry either. But they’re people in the audience and they’re willing to stick around the whole time and give a number to each poem. And what the judges do they give a number between zero and ten. We ask them to use decimal points, so between 0.0 and 10.0 so as to avoid ties. And they judge the poems based off the content of the poem, the performance of the poem, the creativity of it and they come up with these numbers. And out of the five judges we chop out the high score. We chop out the low score. And the middle three scores get added up so the best possible score is a thirty. And it works tournament style just like diving or gymnastics or something like that where we have different rounds that we go through. And at the end of the night, whoever has the highest score wins the poetry slam.

Jo Reed: And is there a topic typically given to the poets that they need to construct a poem around?

Jonathan Tucker: No. If we’re talking purist form, poetry slam, how it was invented in 1986 by Mark Smith in Chicago, there’s not a topic. You can talk about whatever you want. There’s complete freedom of speech. But I should say that poetry slam has evolved greatly since then and people have used it in all sorts of different ways and for different purposes. And so there have been many themed poetry slams that I’ve been a part of and have helped to organize. And those are things that exist. But when it comes to the national competitions and most competitions there normally isn’t a theme. It’s normally you do what you want.

Jo Reed: Okay. The D.C. Youth Slam team…

Jonathan Tucker: Shaka Zoon

Jo Reed: …is sponsored by the poetry organization Split This Rock.

Jonathan Tucker: That’s right.

Jo Reed: And you are the coordinator of youth programming there.

Jonathan Tucker: Yes.

Jo Reed: So, tell me about Split This Rock and the D.C. Youth Slam Team.

Jonathan Tucker: Split This Rock is an amazing nonprofit organization that uses poetry to get people to speak up about social justice, and we use our poetry to support movements for social justice. Around 2008 we put on our first huge festival, where we thought we really need to bring together poets and raise up our voices and say that, you know in addition to writing books, in addition to performing on stages and in these slams, we have something to say about society. And we want to take a key role in public life and bring public discourse and civic involvement to the arts world. And make sure that the poets who sometimes are seen as these people sitting alone in their rooms writing, they’re actually involved in everyday life and that their voices matter and that they should come together and form a community that can speak up and advocate for issues that they care about.

Jo Reed: Tell me about the decision of Split This Rock to sponsor a slam team.

Jonathan Tucker: The D.C. Youth Slam Team -- that’s my heart and my joy. There are some amazing young poets around the D.C. metropolitan area who are writing some very courageous work. And so around 2009, 2010 the D.C. Youth Slam Team was looking for a new organization to host it. The D.C. Youth Slam Team has been around for about 20 years. And so Split This Rock of course had known about our reputation for the D.C. Youth Slam Team, and so it was a great fit. It was perfect. Our students were already speaking up for peace and justice in their own way. And so to combine forces with Split This Rock and to have that home where our poets knew that each year there would be another D.C. Youth Slam Team because Split This Rock would take care of it, that was a really important decision. And I’m really thankful that we did that.

Jo Reed: Poetry is so personal and especially, I think, when you’re a teenager. If they were like me at all, you’re quite vulnerable.

Jonathan Tucker: Yeah.

Jo Reed: And yet at the same time, you also want to be honest in your assessment of it, and compassionate. It just strikes me as kind of a very fine line.

Jonathan Tucker: It’s a very fine line. It’s a very difficult line to draw. I mean, getting teenagers in high schools in Washington D.C. to care about poetry at all and form an afterschool poetry club is a difficult thing. That’s a challenge from the jump. And to get these young men and these young women writing these vulnerable poems that you speak of is not an easy thing, but it’s a necessary thing. And we find that they are already writing these poems. It’s a matter of whether they’re willing to work on them and whether they’re willing to share them with a group of other poets in their school. And so what we do is -- Split This Rock sends teaching artists into the local high schools and the teaching artists help run afterschool poetry programs. And through these programs we recruit students, and we motivate students, and we inspire them and we give them the tools and the techniques that they need to write their own poems. And not only individual poems but group poems as well. We do this big competition called the Louder than a Bomb DMV Teen Poetry Slam Festival. And these afterschool clubs they turn into slam teams and they select four to six poets whether through a slam competition or through some other sort of audition model. They select poets to represent their school at this competition. And so then it becomes very intense where it’s not only them representing themselves and being vulnerable on stage for themselves and for the sake of the message that they’re getting out and the story that they’re telling. But they’re also representing their school in a competition where they’re trying to win. Although they’re trying to express themselves and all of these other things and we promote the good sides of literacy and all of those other things, at the end of the day, it is a competition. And even if the points aren’t are the point, the poetry is the point they would still rather win the competition than not win the competition. And so we send these coaches out to work with them and to help develop their voice and to be comfortable being vulnerable first in front of five or ten people in the poetry club after school. And then in front of maybe 20 or 30 people who come to the open mike at school. And then maybe in front of 100 people who came Busboys and Poets and see them one time. And then hopefully we get them comfortable enough to speak their poem in front of 300 people at the Louder than a Bomb Poetry Slam Festival.

Poem:

Merriam-Webster:

We recommend that you add Columbusing into the latest edition of your dictionary

Columbusing: verb. White people discovering and glorifying existing things in colored communities

You, Webster, of course, have the power to give title to this tyranny!

Haven't heard of the term? Just walk around your city's art district

There, I'm sure you'll be able to find rows of Columbus stores, such as:

Caribou Coffee, American Apparel, or, of course, Urban Outfitters -

Where you can look like a black person from the nineties!

Declare it yours, decorate it in dubstep and step all over the history

Even the most patriotic people will scream

"Con los terroristas!"

But our Harlem shook far before your beat dropped

Our go-go derived from beating buckets and bottles

It was not a joke, not a laugh, nor drunken jump

It was the sound of uncompromised culture

The noise of our city, before being drowned out by cranes and construction work

It was movement, fluid

Shake off the shackles, lend the limbs to the wind

Before 1492, when Christopher Columbus compassed this land and called it his own

People lived here

Before 2000, when metal beasts and business folk compassed our land of DC and called it their own

We lived here

They only acted on it upon discovery

Transformed our chocolate city into vanilla bean ice cream

Jonathan Tucker: We've seen tremendous growth, and some of the students who you would never expect to get up there and be bold with their stories, when the pressure comes, they find what they need to really represent themselves in the best way possible.

Jo Reed: Tell me about what you’ve seen in the young people that you can attribute to their participation in the DC Youth Slam Team or in Louder than a Bomb?

Jonathan Tucker: So it’s hard for me to start with this because I’ve seen so much from so many different students around the area. And one of the most beautiful things about the Louder than a Bomb program which we partnered with the Young Chicago Authors who started Louder than a Bomb in 2001 to bring it here to DC in the DMV area, and from the jump it’s always been about bringing together students who don’t normally meet each other. And using poetry and creative writing and performance as the medium through which they could meet one another. D.C. is a very divided city. And it’s been like that for a long time. And with the increased development and gentrification that we have going on there’s a lot of movement and a lot of change going on in the city. And therefore, there’s a lot of conflict, and a lot of debate going on about who the city is being developed for and who gets represented as Washingtonians. And these poetry slams have helped these young people really find their power and find their voice at a time in their lives when they’re constantly being silenced and being told that they’re not valid. And that their stories are not important and that they are seen as a threat. They are seen not as citizens but as potential criminals. And our poetry programs give them a space where they can just be teenager and just be free and they can write whatever they want. If they want to write love poems because they’re a teenager and they’re in love, that’s cool and we have coaches there who will help them do that. But if they want to write some political poems and talk about the problems of racism and sexism and you know, the war and militarization of the police forces in their communities or of war going on overseas, if they want to talk about these things, we’re here to help them talk about those things and express themselves. And what it provides is this sense of self that I haven’t seen provided to students in other ways.

Jo Reed: I was speaking to Carla Perlo from Dance Place and she says that a child who performs, it gives them a confidence that they can simply take anywhere. That it helps them straight across the board.

Jonathan Tucker: A confidence that they can do anything. Something that they hadn’t imagined before is all of a sudden possible because I risked myself. I put myself onstage. I read my piece. And afterwards everyone is screaming and cheering and all of a sudden I’m on the radio and I’m speaking on the radio. And so my students were on WPGC 95.5 a very popular hip hop station around here and they were able to perform their poems on the air and meet some of these on-air people that they had never thought they would meet. They were able to perform at the Kennedy Center. We went to South Africa last summer.

Jo Reed: I was going to ask you about that.

Jonathan Tucker: We were able to fly all the way across the ocean simply because these kids wrote some amazing poems. And so those types of things really open a young person’s eyes up. I mean they open anyone’s eyes up, really, who sees it. But since we work with teenager it opens these young people’s eyes up to if you try hard, if you dedicate yourself to something and you really put yourself out there, there are benefits that will follow that. And some of it can be seen very easily like a trip to South Africa. And some of it is more invisible and just that team bonding that we have and these best friends that are formed for life now who would have never meet because D.C. is so divided.

Poem:

We're just a little too caught up in the way the world sees us

And the way my people see yours

And the way my people see yours

And the way our people see ourselves

1996: A Jewish girl was born with the Shabbat candles glistening in her eye

1996: A Muslim girl was born with the Adhan ringing in her ears

She only knew of her own [?]

She never noticed that Muslim girl

She never noticed that Jewish girl

Holding the same needles and threads that she did

Sewing quilted generations from stitches and callous palms of their past

Friday prayers

Religious songs

Like God

In Hebron, a 14-year-old Palestinian girl was killed

When a Jewish settler shot a bullet into her right eye

She'll never get to witness her holy land come back to her

In Herzliya, a 14-year-old Israeli girl was killed by a Palestinian pipe bomb

She was trying to eat her dinner at her favorite restaurant by the beach

We are told to stay within the confines of our religion

Of our tradition

As if a young Palestinian girl's life ended by Israeli gunfire

Is worth any more or less than a young Israeli girl's life ended by a Palestinian pipe bomb

This world would rather chew up and spit out our history than help these two girls

That could have been us.

Jonathan Tucker: And so we bring all of these kids together under the power of their language and give them the power to choose how they use that language up on stage, with a microphone, representing themselves. And we find that they represent themselves very well if we give them that chance.

Jo Reed: We can’t just drop South Africa. Tell me about that. How did this trip come about?

Jonathan Tucker: So Washington D.C. has entered into Sister City agreements with many different capital cities across the world. And a couple of years ago the D.C. Commissioner on Arts and Humanities put out a request for proposals for grants interacting with these sister cities. And so as part of this cultural program, we submitted something from Split This Rock saying we should bring our young poets from D.C. and bring them over to the city of Tshwane and sort of show them how young people have played a role in social justice movements across the world with this tangible example of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. And have them see that history compare that to the Civil Rights Movement here in the United States. Compare the post-Civil Rights Movement that they’ve been growing up in to the post-apartheid state that we would visit in South Africa. And come to a better understanding not only of a historical context of who they are as, you know, young African-American teenagers but also a context of as an artist and as a person who cares about social justice what is my role? And what are the different tactics and strategies that can be used to make a difference in my community? We spent two weeks over there. We also visited Johannesburg as well. We performed in Pretoria at the South African state theater. The South African government treated us so nice, brought us around. It was truly a life transforming experience for these young people. The name of our program was called “Fly Language.” And we named it that because our students, their language, their poetry was so fly that their own government wanted to fly them overseas to represent us. And that’s a big thing for a high school person, to put that on your college resume and be like I’m applying to college and oh yeah, I’m a cultural ambassador for the United States going over to South Africa with my poetry. And, oh yeah, I’ve performed at the Kenney Center. The D.C. Youth Slam Team -- they’re amazing. The things that they do with their poetry and as a team collectively just astounds me all the time.

Jo Reed: How did the poetry translate across cultures? How did the people in South Africa respond?

Jonathan Tucker: Mm-hm. They responded much like most audiences respond to the D.C. Youth Slam Team which is utter amazement. These teenagers are truly talented in a way that I just don’t know how to quantify. One example is they competed against the Adult D.C. Poetry Slam Team in this thing we do every year called the David versus Goliath slam. And this year for the first year the D.C. Youth Slam Team won. They beat the adults. And I’ve been encouraging my students to enter the adult competitions. And a lot of these writing competitions aren’t limited by age, although they expect mostly people over the age of 18 to submit. I’ve been telling my students, you don’t need to wait for that. Not only their writing skill, but the way that they perform it with such authenticity, with such vulnerability and courage to get up there and share their stories that are sometimes very traumatic, sometimes very painful -- they amaze everybody. They get to see a whole bunch of other teenagers who are also reading their poems and willing to be vulnerable and that’s an amazing thing. The voice that it gives them, the encouragement that it gives them just to care about how they present themselves is a really important thing.

Poem:

My earliest memory is my mother's voice

Telling me that if I found a bird feather on the ground

It was my father's attempt at communication

At my age I didn't understand if it was because my last name was Bird

Or because the holiest birds flocked around the gates of Heaven

And a descending feather was just his invitation for me to join him

I never understood

But all the years and all the times that I put on my hawk eyes

And looked for every bird feather I could find

I never heard my father's voice

And he never heard mine

But daddy just in case you can understand this

You shouldn't have been taken from me

I know it wasn't your fault and I know it wasn't my fault

But I just feel like I could have done something more

I was only two

Two years old, too little, too late to do anything to change the outcome

Too young to understand that I need more pacifist and pacifiers

Too small to realize that you had planted your roots

With two different family trees

Too dumb to assume for fourteen years that that meant you were just like those other deadbeat daddies

But thank you for the stereotypes that you did beat, daddy

They told me I got my ability to question the world from your Y chromosome

So daddy, had my ignorant assumptions tarnished your medal of honor

Daddy, did you let me keep my mother's last name because you knew I would need to fly to see you again

I would have answered these questions by myself

But I was only two

Jonathan Tucker: So in South Africa they got a standing ovation. And they constantly ask us, “How does this happen? How do you get these most amazing kids? How do you write poetry like that at the age of 15?” And often -- this is my problem with my job -- is that I’m sitting here supposed to help this student edit their poem and they’re writing the most amazing piece and I’m sitting here trying to write my own poems and go compete in the slam. And I’m just like these kids are going to beat me.

Jo Reed: Let’s talk about the performance because part of slam is, in fact, not just reciting a poem but there’s a performance aspect to it, which doesn’t mean it’s inauthentic. But you have to think about how you’re delivering it to an audience. How do you, as the coordinator of youth programming, how do you coach that? Making it clear that you have to think about how the poem is being received but at the same time they need to hang on to their authenticity.

Jonathan Tucker: Yeah, it’s different poem by poem and I guess coach by coach and every poet has a different opinion about it, but one of the things that we make sure that our students know from the jump is that it’s not important whether they win or lose the poetry slam because that’s completely fickle. You never know what the judges are going to do. And that they should be writing to express themselves more so than writing to impress the judges. And that the performance is always just something that we use to enhance the impact that your message has. And what is the message of your poem? Why are you writing? What are you trying to convey? Okay. Now, once we decided that maybe a heightened performance can help bring that across. Maybe we need less performance. Sometimes we need to draw down the performance so that you’re not focusing on my hands or what I’m doing choreography wise or anything else like that but you’re focusing solely on my words, because I have some very important words for you. Other times, the performance is very important. And so it’s a delicate balance that we go back and forth on. The problem with slam poetry unlike other poetry contests is you can’t reread the poem. You can’t re-listen to it. You have only that first take. You’ve got three minutes on a microphone. The judges only have those three minutes to judge you. So they can’t reread what you wrote and see how amazing it was. You have to connect with them on that first instance. So sometimes, it does take a little bit of performance to really let them know how you feel but also what they should be thinking about it.

Poem:

In the fifth grade, swim class was a gym requirement

My predominantly white classmates gathered around the edge of the pool

They wanted to watch as I disproved the myth

That there is no buoyancy in black boys

I saw the congregation of hazy white clothes gleam down at me

Felt my skin tighten and twist

In 1964, a white hotel manager poured acid into a pool in which blacks were staging the Saint Augustine swim-in

Wonder how tight their skin got

History will gossip of black bodies paving ocean floors

Like drowning family trees

This is why waves taste like tears

This is why oceans are salted

Black bodies have always known pain when it comes to water

I pressed my ear to an abandoned skull

Hear the thoughts of the woman who used to live inside of it

The struggle of screams

They tried to tell me it was the sound of the ocean

That I was holding a conch

But they didn't know

They mean god's first gift to humans was a seashell

But they didn't know her voice could always be heard

A reminder that whether slave ships, fire hoses, levees, or tears

Black bodies have always known rebirth when it comes to water

Young, we're taught the rules of float or flight

When it rained, we never ran, we stood

We covered our heads, not in fear

But in prayer

We have always been the middle passage

Between ashes and holiness with a graveyard at our feet

Our savior's faith walking on water

No bullets, no fists, no chains, no whips can hurt an ocean

We are children of the sea

Underwater is where we have always learned to-

Up on the shore they work all day, out in the sun they slave away

While we're devoting full time to floating

Under the sea

Jonathan Tucker: And it’s about bringing the best energy that you have and giving it to that audience. And one of the things I love about poetry slam is that it’s an interactive thing. There’s an interaction between the audience and the poet. And that energy transfer is real. It’s the difference between Broadway and a movie, the same exact thing. There’s a real energy being transferred currently. And you have to experience it right then. And if you do you will get those chills up your spine. And I would show my students the goose bumps on my arm when I knew that they were doing the poem right. I would say I felt it in my spine. This was a magical moment that just happened right here and you created that.

Jo Reed: And your team, the D.C. Youth Slam Team --

Jonathan Tucker: Shaka Zoon [?]

Jo Reed: Just won first place at Brave New Voices and that was out of 50 teams.

Jonathan Tucker: Yeah, 50 teams from all across the world including our friends from South Africa, the Cape Town South Africa team was there and they were on final stage with us in the final four. But it was amazing. It was the first time D.C. has ever won the Brave New Voices International Youth Poetry Slam Festival. Like I said, we’ve been going for 20 years. We hosted it here in Washington D.C. in 2008 when it was featured on HBO. But this is our first time winning first place. So we’re really thrilled and very proud of our students.

Jo Reed: The D.C. Youth Slam Team is competing at the National Book Festival this year and it’s the first time there’s a poetry slam at the National Book Festival.

Jonathan Tucker: That’s right. We’re very excited. Yeah. Saturday, August 30, from 6:00 to 7:30 P.M. We’re going to be on the National Mall in the poetry and prose pavilion. And yeah, it’s going to be a poetry slam, a themed poetry slam about books and reading and literature and how much we love literature and reading. And it’s a limited poetry slam. There’s only about eight or ten young poets competing and they’re some of the best young poets in the area and it’s hosted by one of the coaches of the D.C. Youth Slam Team, Elizabeth Acevedo. She’s the reigning world champion Adult Beltway Poetry Slam Team.

Jo Reed: You’re a poet as you mentioned, what led you to working with young poets?

Jonathan Tucker: So I was working with young people before I was really working with poetry. I had done poetry myself but I was never working with it. I was never performing and getting paid for it and stuff like that There is an amazing nonprofit organization in D.C. that changed my life, and really redirected my path. It’s called Operation Understanding D.C. and it’s a black and Jewish cross cultural dialogue group for high school juniors. And so I spent a year in this program and I learned all about the Civil Rights Movement and many other movements and many other histories. But the thing was, we spent a month in the summer on a bus going down south together and studying the Civil Rights Movement by meeting the people who are involved in it and going to the historic places. And it really opened my eyes to the injustices that are still going on in the world, and that there are people still fighting for these things and dedicating their lives to it. It’s not something that is a bygone movement. And so through that program I just got re-inspired to life and to pursue something greater than money. I understand the necessity of it but at the same time it can be insidious and it can be a problem. So basically that organization-- I came back and started working for that organization. I was in college, actually, my last year of college I started facilitating that program and working with young people then. And I started leading them on that same journey down south that I had been going on and that was my first eye opening experience where I had the power to work with young people and it was beneficial. It was good. Everyone grew out of it. And so I had been working with young people. After that I was working with a paralegal in D.C. I was going to go to law school but on the weekends and stuff I was volunteering with these nonprofit organizations and working with young people and doing tutoring and things like that. And eventually when I made it on to the D.C. poetry slam team I had to take off an amount of work that the law firm would not allow me to take off. So I chose to get fired to go to a poetry slam. And that sort of tipped the balance for me in terms of, you know what, maybe instead of dedicating my life to law, I should dedicate it to poetry and education and working with these young people. And ever since then my path has been geared towards empowering young people to speak up for themselves and to find the tools that they need for success. Because I had people here to support me coming up, and that really changed my life in a significant way. And I’ve seen how poetry can really change people’s lives in a dramatic way that they would have never expected.

Jo Reed: Jonathan, thank you. I really appreciate it. Thank you for all of the work you do.

Jonathan Tucker: Thank you for having me here. It was my pleasure.

Jo Reed: You’re very, very welcome. And I’ll see you at the book festival.

Jonathan Tucker: Awesome.

#### End of Jonathan_Tucker.mp3 ####

Music Up

Jo Reed: That's Jonathan Tucker--he's coordinator of youth programming at Split this Rock and he shepherds the DC Youth Slam Team. We also heard the following young poets: Thomas Hill, Malachi Byrd, Amina Iro and Hannah Halpern, Chyna MacCombs and Morgan Butler.

You can hear these poems and others from the team on YouTube. Just search for DC Youth Slam Team. And come to the Book Festival, where you can hear them in person. Go to arts.gov for more information.

You've been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Next week we're taking a holiday, but we're back on September 4th with a new series, Hidden Lives. They may be a grocer, a mechanic, or a maid; but they also make beautiful art. We'll be looking at some of the people who have jobs and careers, but somehow still continue to create their art. We kick it off with painter and blue color worker, Ralph Fasanella.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter.

For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

###

The DC Youth Slam Team is an award-winning internationally acclaimed poetry group. Listen to their poems and find out how it all comes together.