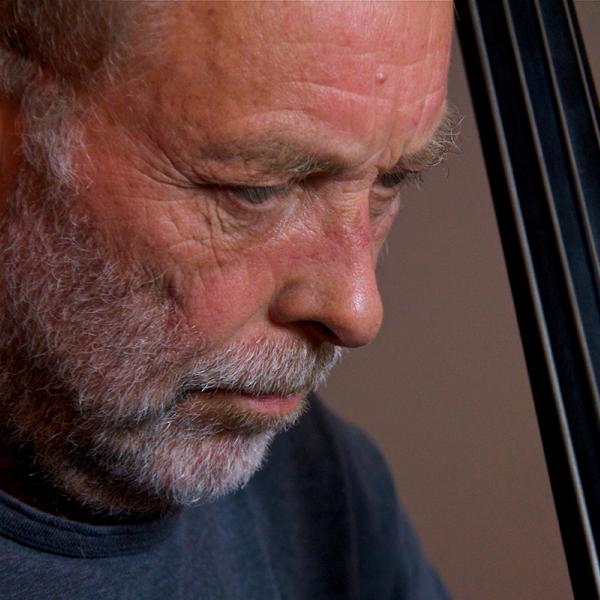

Howard Herring

Music Credit: “4 Dances” from Estancia by Alberto Ginastera performed by The New World Symphony Orchestra at the grand opening of the New World Center, Miami Beach, Fl; 2011

(Music Up)

Howard Herring: It's a young audience; it's a diverse audience. It's an active audience- they tweet, they text, they video, they share it with their friends. People actually find out that it's going on and come here, as a result of the social media. We have a line out front; it's a hot ticket. It's a pretty amazing event.

Jo Reed: That was Howard Herring— the President and CEO of New World Symphony…and this is Art Works— the weekly podcast produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed….

The New World Symphony is the brainchild of conductor and National Medal of Arts recipient, Michael Tilson Thomas. He was concerned that, after getting a degree and often a graduate degree, any number of talented young musicians were left to flounder about on their own. Tilson Thomas believed they needed a place where they could continue to hone their skills, launch their careers and find a community. In 1987, in Miami, Florida Michael Tilson Thomas made that happen. The New World Symphony is the only full-time orchestral academy in the United States which prepares musicians for careers in symphony orchestras and ensembles. And its Artistic Director is Michael Tilson Thomas.

Co-leading the charge in the development of the New World Symphony’s innovative programming is its president and CEO, Howard Herring…. For the past 14 years, Howard has had the boldness to imagine the presentation of classical music in the 21st century— the jewel in his crown has to be co-developing the academy’s new campus: the spectacular New World Center, which was opened in 2011. Designed by architect Frank Gehry, it was created to reimagine the concert experience for performers and audiences. Acoustically almost flawless, visually theatrical- it is a marriage of sight and sound. Performances vary: they include full-orchestra concerts, a new music series, percussion consort series, small ensemble concerts, a family series, and special festivals and recitals. Some performances start at 9:30 or 10 o’clock at night; some last 30 minutes; some are broadcast outside on the walls of the building itself. But this isn’t innovation for innovations sake, as Howard Herring explains. All of this contributes to the experiential training of young musicians, which remains the heart of NWS's mission.

Howard Herring: Our exact title is the New World Symphony, America’s Orchestral Academy. We are a graduate program, a non-degree-granting fellowship program, and we are selecting talented young musicians. They must have at least an undergraduate, the majority of them masters these days. We’re bringing them from distinguished music schools and conservatories in this country and also around the world and they come to us for a three-year fellowship, pursuing a curriculum that we describe as experiential, and we are preparing them on three levels. The first is all about excellence in playing, the second one has to do with engagement both in the hall and online, and the third category is leadership, entrepreneurial and entrepreneurial-- how you get yourself ready to craft your own career and be your best, pursuing your unique talent and expression.

Jo Reed: How many students have gone through the program?

Howard Herring: We have almost a thousand alums all over the world. The thousandth alum is on stage this season for the first time so we’ll hit that mark in about two years. And they are in orchestras and ensembles, also in music faculties. Some of them are pursuing some pretty wonderful educational experiments and three are now running orchestras; the president of the Milwaukee Symphony, the Indianapolis Symphony and the Knights in New York are all three New World alums. So we are having an impact and we’re very proud of that and our alums are now coming back to coach the fellows and be part of the extended network. One of our alums says that we are the Harvard MBA program of classical music and he’s not far from wrong there. He’s very much on target because we’re able to get our guys ready but also as they move out there there is a really wonderful robust network of support in the field and then as we bring alums back making things happen here at New World Symphony.

Jo Reed: I am hardly breaking any news to you when I say symphony orchestras are certainly going through very challenging times. The symphony orchestra itself is being questioned as possibly archaic, and I know that’s something that you confront fairly directly at New World Symphony.

Howard Herring: Yes, we do. We envision a strong and secure future for classical music and we make it our business to reimagine, reaffirm, express and to share this music with as many people as possible. That’s our vision statement and we’ve built programs to back it up. We are pursuing new audiences in a variety of ways and we have a cycle of development for this engagement which begins with identifying a specific audience, then building an experience around the living pattern of that audience, the things that they do day to day and what their preferences are. We do this by adjusting start times, by adjusting durations of concerts and always a lot of conversation between musicians and audience members. In the center of that experience is an uncompromised performance of classical music. No compromise on the repertoire, or on the excellence of the performance. It is at the heart of this larger experience. Once they've come and been part of it, we then survey in an aggressive way. We have a survey system that is both paper surveys and online surveys but also focus groups and we try to understand what happens to them in that experience, what they liked, what they didn’t like, what resonated, what was-- what had intrinsic value, and that leads us then to re-calibrating. So we have three alternate formats and we are gaining audience in a rather remarkable way.

Jo Reed: I’m going to just interrupt you for one second because I would like you before we talk about that to talk about the New World Center, which opened four years ago. Explain how the design of that building both inside and out reflects the goals.

Howard Herring: We imagined a program for the New World Symphony that’s experiential curriculum and it took us just over three years to come to grips with who we wanted to be twenty and thirty years from now, and we took that program to Frank Gehry. Frank and his team began to interpret our ideas. Michael Tilson Thomas was intent on creating a primary façade that was an invitation. Tracking back in his career all the way back into his twenties when he was in charge of the New York Philharmonic’s Young People’s Concert broadcasts, he was very much aware of what electronic technology and visuals can do for and with music so there’s a lot of projection inside our space. We’re able to reimagine the presentation of classical music and we do that in a variety of ways, integrating video in music, adding a theatrical element, bringing the audience very close to the performers; proximity we think makes a difference. Just the lighting of the stage is already a different feel at the New World Center in part because we are capturing some of our concerts for the Wallcasts. This is where we turn the building inside out and live and in the moment simulcast the concert on the primary façade of the building, but it’s interesting because with all that light for video it-- the light bounces off the floor and the faces of the players are more clear, the audience is-- we’re steeply raked so that the audience is gathered around the primary stage, and there’s a lot of interchange and a lot of visual interchange between the players and the audience.

Jo Reed: And it’s not a very big theatre.

Howard Herring: Only 750 seats.

Jo Reed: So it’s rather intimate.

Howard Herring: That’s right. We program for the fellows and we want to always play to a full house and we do a good bit of experimentation so if we have a popular program we play it twice, we’ve even played them three times, and if we have a program that’s more experimental we’ll play it once, but we pretty much always have a full house at the New World Center and that’s something that we feel is important for the players and for the audience.

Jo Reed: Let’s talk about how you go about now trying to attract a younger, more diverse audience because as we know classical music has some challenges and part of that is the audience is aging, and the art form is often perceived as elitist and you kind of knocked those pins down, one, two three.

Howard Herring: We have indeed. We think this music speaks to everyone and we begin each day believing that we will find ways to distribute this music, to present this music, to integrate it into a community in such a way that people can be moved; they can be transformed by the performance and by understanding more about the music. And that goes back to first of all excellence of performance but also we do a 30-minute performance; we do it at seven and eight o’clock over an-- the course of an evening. We have affinity groups who are with us. We have yoga students; we have bicyclers; we have runners. This is part of their larger evening but we’re up in the 45 to 50 percent range new to the database for those performances. We do 4 evenings like that per year.

Jo Reed: Let me interrupt right now because I would be all over that. When I read about that I thought it was brilliant because a half hour to an hour for me is a perfect evening of music with few exceptions, but I’m pretty notorious about going for the first half of a concert or the second half of a concert. Unless it’s a program or a musician or a conductor that I’m truly, truly interested in.

Howard Herring: So one of our survey questions is to ask people what they felt about their aesthetic growth and the emotional resonance of the evening. And it turns out that a 30-minute performance is just a touch more powerful emotionally and aesthetically—

Jo Reed: I believe that.

Howard Herring: --than a traditional performance so short can be quite good. And then when you’re in that 45-percent-new-to-the-database range so you’re bringing people for the very first time you’ve really crossed a barrier; the next step of course is can you bring them back. So we’ve been at this for six years, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation very much behind us here and wanting us to go find these audiences and build our own audience but also make models for other orchestras. But in fact we have about 13,000 new people as a result of this work over the last 6 years and we’ve brought 33 percent of those folks back once and we’ve brought 19 percent back twice, and they don’t always come back to the performance format that was their point of entry. They might come to a 30-minute show and then come the next time to a 60-minute show or to a full-length show or to the wall. So we’re not trying to predict where they come back; we just want to observe and learn more and more about why they come back, what was the intrinsic value that brought them, and then capitalize on that. So that’s our goal. And we have seven professional orchestra partners. They’re all having success with short-form performances and it’s expressing itself in different ways. We see it happening-- we see it working, the contextualization. I think people are very much eager to get more information about this music and I think it helps them then be transformed in that moment as well as develop a long-term relationship with the music, but then with the players as well as they go back and forth in the dialog after the performance is over.

Jo Reed: Now of course what you’re doing at New World Symphony, interacting with audience, is part of the training that your fellows have. What about with some of your partners where the musicians might not have had the benefit of that? Is that a leap for them? Is it difficult or do they embrace it or sometimes both?

Howard Herring: You know, I think it’s a leap for all of us. People often say to me, “Well, you have the advantage of having young players.” We have some conversations with our fellows. Yes, they’re younger, perhaps more pliable, but we have to be careful about the dignity of the presentation and the focus of the audience and we need to always be mindful of bringing these new experiences together in such a way that the music is at the very heart of it, but what we’re discovering is that the musicians in our seven-partner orchestras when they begin to see the results, when they realize that they are indeed finding new audience, their decision to continue is an easy one because they understand that this is about the future of the art form and I think that will continue. When we think about what an orchestral season, what it looks like in ten years, there’s going to be three or four product lines, maybe more, and there’s going to be specific audiences for those product lines. I hate to use a phrase from the corporate world that sounds maybe too clean and cut and dried, but in fact if you are a lover of classical music in 30-minute doses and you happen to then like to take a yoga class after that in the park across from the concert space then why not let that happen and let that be your point of entry and then your continued relationship with the art form and with the institution and the musicians. No reason not to see the future in that way as far as we’re concerned.

Jo Reed: Your late night concerts, which are called Pulse concerts, are extremely successful. Describe them. What happens there?

Howard Herring: You bet. It is absolutely true. Miami Beach is a late-night city and we began our lives in the Lincoln Theatre and that’s on Lincoln Road, and a good bit of this alternate-format started because we could so easily get people to come off of Lincoln Road and into the theatre if we just explained to them what was about to happen. And we did a tango festival and we simulcast-- we put a screen out on Lincoln Road and chairs and we simulcast the concerts, and we would teach people to tango before the concert started. So this whole business of informality and use of screens and dancing and then bringing people inside and letting them listen but having just danced, all that was sort of the early steps, but when we began to think about the new facility, the new campus, the business of flexibility was uppermost in our mind because we could see that in a traditional concert hall you can only make a certain number of moves and they were relatively small compared to the old style of we play; you listen. So as we pushed our way through the design and as Frank Gehry and his team kept asking us these terrific questions, “Well, what if and what if and what if,” we realized that the business of juxtaposing it, mixing genres-- musical genres, was something that we could do quite easily if we had this flexibility. So-- that takes us to Pulse where we pull the first seven rows back but we even drop the fourth ring of the orchestra so people in the audience can actually walk down through the orchestra while they’re playing. It might sound sacrilegious to some. I can tell you that people have never been that close to the fire; they cannot believe the energy that comes off a stage and when they stand in the middle they’re transfixed. So all of that value comes from these new relationships that are being developed because you can put the audience so close to the players and vice versa. Now where that all goes and does someone come to a Pulse concert and then come back later? John Adams’ “Short Ride on a Fast Machine”; it works every time. Are they going to come back and hear some of John’s music, at a full-length concert or a one-hour performance? We hope they do and we think that there’s links to be made there and we’re working hard to make that happen.

Jo Reed: I’m so curious about the mechanics of this, Howard. What happens? Does the deejay spin some tunes when the orchestra takes a breather and then it goes back to the orchestra? Does it go back and forth?

Howard Herring: Yes, that’s how it works. So we start up at about 9:20-9:30 and the deejay begins relatively low in terms of decibel level-- kind of getting things started, and 10:20 we play the first orchestra set. The sets are about twenty minutes long and then the deejay takes it back and then at about 11:20 we play the second set and at the end of that orchestral performance the deejay just turns it loose; it becomes a dance party. Meanwhile, at midnight we go down the hall and we play chamber music in our 100-seat chamber music space for those who want to come and listen in the quiet. And if you can believe it we may have 5 or 600 people in the performance hall listening to the second orchestra set and a hundred of those folks are quite happy to walk down the hall and listen to chamber music at midnight. So, that was an experiment. We didn’t know whether it would work or not, it works quite beautifully, but the idea is to not just have the deejay stop and the orchestra start. We’ve begun to make arrangements of music so that the deejay will be playing and then all of a sudden the audience realizes that the sound is coming from the stage, not from the speakers and that’s because we’ve bridged over; we’ve pulled harmony and melody out of the deejay leaving the rhythm and letting the orchestra then pick up that rhythm and start to add harmony and melody back in. They play that transition, the cadence. Then there’s a moment where the conductor announces what’s about to happen and off we go; it’s the orchestra set. So by integrating one and the other-- we’ve watched people get excited and it’s even more intriguing to them as a result of that. So that’s how we run it. It’s 1400 tickets and people go and come as they please, starts at 9:30, ends at 1:30, 40 percent new to the database, 46 percent identifying as non-white. We’re very proud of that statistic. Median age is 38; we know that it’s actually lower than that because surveys tend to skew high in age and you know that from walking the space on a Pulse night. It’s a young audience; it’s a diverse audience; it’s an active audience. They tweet; they text; they video; they share it with their friends. People actually find out that it’s going on and come here as a result of the social media. We have a line out front. It’s a hot ticket; it’s a pretty amazing event.

Jo Reed: Are people shocked, shocked, shocked that you are doing this?

Howard Herring: Some people are, but you know, I guess some people find it undignified. But once you’ve spent 30 minutes at Pulse you realize just how serious we are about bringing this music forward in a way that will speak clearly and dramatically and vibrantly, and then when you talk to the audience, and when they talk to us in the focus groups, they are reporting that the music that we are performing as an orchestra is at the heart of this experience and in part because they’re surprised by that. They’re coming to something ‘cause they’ve been told it’s a hot ticket. Many of them just don’t go to orchestra and the next thing they know an orchestral ensemble has knocked their socks off. So there’s this wonderful element of surprise and we try to capitalize on that. So we think that by cutting back across the grain; by surprising this audience we’re actually even more effective than we might otherwise be. We’re catching them off guard and that’s a beautiful thing.

Jo Reed: You, of course, are still continuing to present classical music in a more traditional way.

Howard Herring: Absolutely. I spoke to the Emerging Arts Leaders Conference at American University and I took them through the three alternate performance formats and the statistical results and some of the intrinsic values that we’ve discovered, and one of the first questions was “Don’t you do traditional?” We do 70 performances at the New World Symphony across an academic season. Each one of these alternate performance formats happens on two weekends so we set aside-- and there are three alternate formats so there are six weekends that are set aside for this experimentation, but in fact those weekends have traditional performances going on as well. So, six nights out of seventy is experimentation time. What’s interesting is to watch the experimentation begin to migrate into some of our other formats that were originally more traditional, and the fellows of course are quick to pick up on this. They’re solid thinkers, they’re creative and entrepreneurial individuals, so they’re starting to include some of the aspects of the alternates in their own presentations. They have a good bit of the season is made up of concerts that are designed by the fellows; that’s becoming an ever more important part of New World Symphony. So it’s-- what goes on in those six weekends is beginning to spread out into the rest of our season, but many, many times it looks very much like a concert would have looked like in 1962 because there’s tremendous value in that kind of presentation and we don’t-- we’re not going to walk away from that.

Jo Reed: Do you play an instrument?

Howard Herring: Well, I’m a pianist in my deep, dark past. I still play for myself. I play for myself occasionally but I try to practice in the summer; I don’t always get that done.

Jo Reed: What first drew you to music?

Howard Herring: Well, I grew up in a little town in Oklahoma, it’s where Continental Oil Company, now Conoco, was founded and I was quite lucky. The research and development division of Conoco was in this little town. And scientists were intent on having a full life and there were some very smart people who just made sure that there was a community concert association and that the schools were filled with music. Throughout my high-school days, we had a full orchestra rehearsal, every day. We would have at least two concerts at the end of the season when all of us who had a concerto to play could play it with the orchestra; we would accompany one another. We did Handel “Messiah” at Christmas and at Easter, full-blown orchestra, chorus. It was a music town and I also had some really terrific teachers so I loved it from the time I began to sit at the piano and I just was lucky enough to be in an environment that supported me throughout. I actually worry because there’s so-- it’s hard to know whether we can even come to terms with this-- with statistics and data but we are told that the United States is-- the public schools are less able to deliver consistent and high-level music training. I know that our fellows have grown up-- the majority have grown up in cities and in towns where there has been a strong music program and just like I was supported they too had what they needed to develop their talent. I think we’re a better society. I think that we are smarter as individuals. I think that in a creative economy, which is certainly where we are now, you had better be ready to develop that aspect of your personality and your intellect and your emotion so it’s a critical thing. I just got lucky, and I hope that we as a society will go back toward more serious music making throughout the public-school systems.

Jo Reed: Amen to that. Okay. What’s next for New World Symphony?

Howard Herring: A good question. So, we want the fellows to be ever more involved in these experiments, we want them to begin to drive these experiments, and it’s not just the new audience. We work hard at integrating video and music and theatre. Michael Tilson Thomas is a master at crossing genres, mixing genres. We also are beginning to think about the capture of teaching moments. We’re out there right now in a beta 2.0 version of this online reference; we call it Musaic. We have nine partners, major conservatories and music schools in this country and in Europe, and we’re experimenting; we don’t know quite what this all means yet, but we think that there will be a significant help to musicians of the future. I’ll give you an example. We do a lot of new music, we do a lot of music by living composers, and in all cases-- we’ve played as many as 25 living composers in an academic season and in each case they are with us. Most often they come in person but if they can’t be here in person they come on the Internet so we are able to listen to them describe the inspiration for a piece of music and then the specifics, I want more flute; I want more percussion there. We’re able then to capture that and have it for posterity. The reference I always make is, as a pianist, there’s four or five big questions I have of Beethoven. I’ll never get those questions answered from him but had he lived in a digital age and someone would have asked him about those particular instances, we’d know. So, there will be greater clarity going forward and we’ll be listening to composers on voice describe what they intend and we think that’s quite valuable.

<Music>

Jo Reed: That was Howard Herring. He's the President and CEO of New World Symphony. You can find out more about New World Symphony at NWS.edu. You've been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAarts on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Reimagining the presentation of classical music.