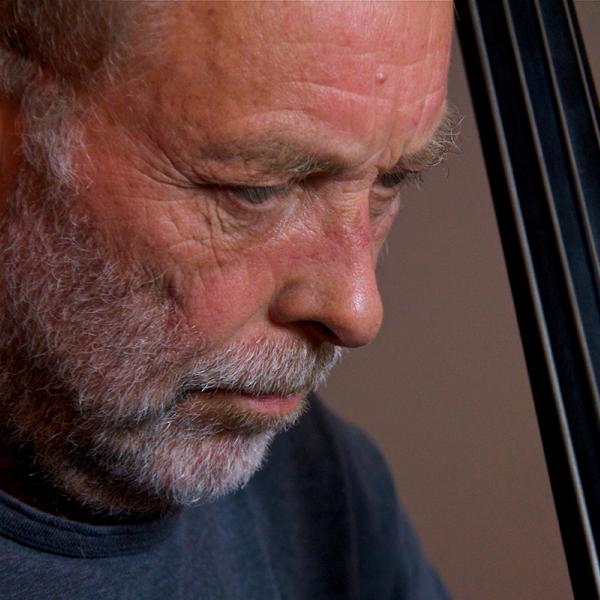

George Wein

George Wein—Podcast Transcript

George Wein: What drove me into jazz was pop music back in the '30s. I studied classical piano when I was eight, nine, ten years old, and playing things like "Liebestraum" and I used to sing. "I Wanna Go Back to My Little Grass Shack in Kealakekua, Hawaii." My mother used to play a little piano. She wasn't very good, but she could read sheet music. But I always wanted to accompany myself, so I started taking pop piano lessons, which turned into jazz piano lessons. And then I started listening to jazz, and my brother would bring home records. I remember he bought a record player that had 13 Bluebird records with buying the record player. And I mean, those records with Louis Armstrong, "Saints Go Marchin' In," and Jimmie Lunceford "White Heat," and all these jazz records, and that's where I got the message. Jo Reed: That was the great jazz impresario and 2005 NEA Jazz Master George Wein. Welcome to Art Works the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation's great artists to explore how art works. I'm your host, Josephine Reed. Although George Wein has been displaying his chops as a jazz pianist since he was a teenager, the 87 year old is known primarily as Jazz's leading impresario. In 1950, straight out of college, he opened a jazz club in Boston and called Storyville. There he booked most of the leading jazz musicians and went on to establish a Storyville record label. In 1954, he literally invented the idea of an outdoor Jazz Festival when he launched the first one ever held in the United States at Newport. And the Newport Jazz Festival went on to become an annual tradition. Wein went on to start a number of festivals in other cities, most notably the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, known to all as Jazz Fest. Branching out a bit, he also established the now-annual Newport Folk Festival. His company Festival Productions has also run large scale Jazz events in cities around the world, including Paris and Tokyo. In 2007, at the age of 81, Wein decided to take a break and sold his production company. But two years later, when the successor company was headed for bankruptcy, Wein jumped back in the game. He was determined that the jazz and folk festivals live on. To that end, in 2010, he founded Newport Festivals Foundation, a not-for -profit whose mission is keeping the Newport Jazz and Folk Festivals financially viable and musically vibrant. George Wein has received many honors for his work - let me just highlight a few. He has been honored at the White House by two American presidents, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton. The Association of Performing Arts Presenters, or APAP, presented him with the Award of Merit for Achievement in Performing Arts. And of course, he's been an NEA Jazz Master since 2005. I met George Wein in his New York City apartment the week of the 2012 NEA Jazz Masters' Awards Ceremony...I asked him to tell me more about learning to play jazz piano as a teenager. George Wein: I started listening to small band jazz and collecting records. Then I started to play more and learned this magical thing known as improvisation. How did you do that? Then you learn how to do that, and then that's the rest of your life. I was locked in, and I organized my own band when I was 15, 16. I was like one of the kids with a rock band, except I had three trumpets and two trombones and four saxophones and a drum, bass guitar, my cellar, my house in Newton, Massachusetts. And we were playing "In the Mood" and "Tuxedo Junction," and all those arrangements of the big band, and it was the same thing as a kid in a rock band in his garage band now. And that's where I learned. Jo Reed: Do you remember the first jazz concert or club or just live performance you saw? George Wein: I don't know that I remember the first, but I know that I used to go at a very young age to hear Cab Calloway's band at the Southland in Boston, and that's a band that had Cozy Cole on the drums and Dizzy Gillespie was on trumpet. I remember the first time I heard Duke Ellington. Jo Reed: Oh, tell me about it. George Wein: I knew of course how important Duke was - I'd heard some of his records, but to hear him live...and I didn't know the guys in the band, and when Johnny Hodges stood up and played, I felt gooseflesh all over me at that sound. He wasn't even playing an Ellington tune. He was playing a tune called "Whispering Grass." But when that beautiful alto came into my heart and my psyche, that changed me forever. And these these things last with you till the rest of your life. Jo Reed: You played professionally for a while, didn't you? George Wein: Well, I still do to a degree. I mean, I've been playing this year more than I have in the past few years. I love to play, but I started while I was college. I came out of the Army and went back into...went to school. I went to Boston University. And while I was at Boston University, they needed a piano player for Maxie Kaminsky and Pee Wee Russell, and Miff Mole-- three famous, legendary figures. And they needed a piano player, and I was one that was known, and they taught me the Dixieland tunes, and the next thing I know I was working six weeks with them, seven days and Sunday afternoon, while I was going to college. And then I went to work with the Edmond Hall Quartet in '49, and I was there for like two months or three months-- I don't know. And all the time I was going to school and working seven days and nights-- seven nights a week and Sunday afternoons, and going to school. I never thought I'd be a piano player. I'd been playing all these years, but I mean, I was still a student, and somebody said, "Open your own club." Of course I'd been working in clubs in Boston, and a lawyer said to me he thought that I had a head for business, which I really didn't, but I at least understood that if you spent 10 dollars you had to take in 11. That I did understand. And so I leased a room from a hotel, and I started off with the same kind of music I'd been playing. I had Bob Wilber and his band. But then somebody called me from an agency and says, "Why don't you use George Shearing?" I didn't even know what George Shearing was doing, but he had a big record called "Jumping with Symphony Sid," and "Lullaby of Birdland," and "September in the Rain." And I put a little ad in the paper-- George Shearing-- I was paying him a lot of money-- 2500 dollars a week. I had never paid more than 900 or a 1000 dollars a week for a band. Next thing I know, the place was absolutely packed-- sold out every-- for eight days, sold out. And I guess that's when I realized that I might be a promoter the rest of my life. Jo Reed: Well, where did the name "Storyville" come from? George Wein: Well, that's the history of jazz. Storyville was the red light district in New Orleans, and was named after Alderman Story in New Orleans who wanted to relegate all the sin to one section of the city, and that's where Lulu White's Mahogany Hall and all those fabled, mythical names-- that weren't so mythical. Those names came from the history of jazz, and so they rewarded Alderman Story by naming this section of the city after him. They called it Storyville. And I just called it Storyville: The Birthplace of Jazz. That was what the name of my club was, Storyville. George Wein's Storyville. I always put my own name in there. I don't know why. I guess because I liked to see my name in the paper, and since I was paying for the ad, I could my name in the paper. George Wein's Storyville: The Birthplace of Jazz. Then one day Sid Catlett was playing drums with Bob Wilber, and Louis Armstrong had a concert at Symphony Hall with his All Star Group-- Cozy Cole and Barney Bigard and Jack Teagarden, Earl "Fatha" Hines-- all the greatest names in jazz. And I gave Sid, who had played with Louis, said, "You go down to Symphony Hall and get those guys coming back to the club." And I'll never forget this night as long as I live. One by one the guys came in, and Sid, as they walked in the door, Sid brought them to the stand. "And here comes Barney Bigard," and he walked right up on the stage, started to play. "And here's Earl "Fatha" Hines," and he walked and goes to the piano and sits. It was a small room, and they'd come in the big, and he was up the front. And the last one to come in was Louis Armstrong. He walked right to the stage. It was like it was rehearsed. It wasn't. And he sang "Sleepy Time Down South." [Musical break - Louis Armstrong's "Sleepy Time Down South"] George Wein: And the electricity in that room was so incredible that I said, "This is what I have to do. I have to be associated with the great people." And that's what directed my life. Jo Reed: You played there with Lester Young. You played the piano with Lester Young. Tell us that story. George Wein: That's one of the funniest stories. I had a lot of chutzpah saying I was going to play with Lester. I loved the Basie style and the swing era. I hadn't-- I'm not a-- I'm still not a bebop player. I play more modern than I used to, you know I played sort of a simple, Basie, Teddy Wilson style of piano playing. Lester had great piano players who played with him in the previous eight or ten years of his life, but they'd all been bebop piano players. So I put together a band with Buck Clayton on trumpet, who'd played with Prez in the old Basie band, and I had a good bass player and a drummer. And so Prez came in by himself, and was sitting talking, and he says, "Who's going to be on trumpet, Prez?" He would call me Prez, since I was the boss. I said, "Buck Clayton." "Oh, Lady Clayton, that's fine, man." I said, "Marcus Foster...," and then, "Who's going to be on piano, Prez?" "Well, I'm going to be on piano, Prez." "You're going to be on piano, Prez?" And this conversation went on like that. "Well, I know your tunes, Prez." "Oh, well, cool, Prez." So we get on the stage-- he won't get on the stage. And I said, "What do you want to play, Prez?" "Whatever you're feelings, Prez." I said, "Well, how about 'Pennies from Heaven?'" He said, "That's cool, Prez." I said, "What key?" "Whatever your feelings, Prez." And he wouldn't get on the stage. And I said, "What tempo?" "As you wish, Prez." So I started playing. I played a chorus, and I says, "Prez?" He says, "Have another helping, Prez." I had to play four choruses. After I played four choruses, Prez picked up his horn and came on the stage and said, "You and I are going to be all right, Prez." And my heart just went like this-- I says, "Thank god." Jo Reed: High praise, indeed. George Wein: I mean, I had a lot of guts, because I wasn't that good a piano player. But I did know how to comp for him and play simply, not get in his way, and we had a ball. Jo Reed: You played with Charlie Parker in Storyville too. George Wein: I just did one number with Charlie Parker. I had the Mahogany Hall All Stars downstairs. We had two clubs-- Mahogany Hall and Storyville. And the Mahogany Hall had traditional jazz and the Storyville had at that time more contemporary music. And so Sunday afternoon we'd have jam sessions. So Bird was playing upstairs, so I asked Bird, "Come up and play a number with us." So we played "Royal Garden Blues." And when he started to play the blues, everybody turned-- he was so strong and so fantastic, and it just wiped everybody out. One chorus, and that was it and something you never forget. Jo Reed: George, who was the audience that came to Storyville? George Wein: Boston had a very interesting group of people because all of the colleges, Harvard and MIT and Tufts and Boston University. And we drew a lot of the faculty members they liked jazz, more than the students. Because the students couldn't come-- there was a 21-year-old law about drinking beer, and they just drank at home. They'd go out and get the beer and drink it in their parties, but they couldn't drink in public. And so we didn't draw a lot of the kids. And there was not a large African-American population in Boston, but there was a significant population that liked jazz that came out of where Duke and Basie were part of their social life, and we brought and we sort of broke a few barriers down in that respect. And we drew an audience, a lot of older people that came out of the swing era, and they liked jazz. Still very similar to today; jazz draws an older audience, doesn't draw a lot of young people. And so we started the Storyville Jazz Club for Young People, so we had a young crowd and some of those people that joined in those days, I still run into them. The Storyville Jazz Club became important in the history of Boston's jazz scene, and it was very important in my life because I learned my trade at Storyville. I met all the artists, everybody working-- Art Tatum, Charlie Parker, Dizzy, Miles, Duke, Louis, Ella, Sara, Carmen. Jo Reed: Billie Holiday gave one of her last performances at Storyville, didn't she? George Wein: Her next to last performance was at Storyville. I had been in Europe, because I had started doing business in Europe, and she'd been there the whole week. I came back, and it was a Sunday, and she was doing an afternoon and evening, 20-25-minute performances, two in the afternoon and three at night. And I sat the whole day, and I went up to her afterwards, says, "Billie, I can't believe it. You sound like you did 20 years ago, it's just fantastic. What's happened?" She said, "I'm straight now, man, I'm straight. You got to help me. You got to help me." I said, "Well, good. Look, I'll call Joe, her manager, agent, and said, we'll do Newport." And two weeks later she was at a club called the Blue Moon Café in Lowell, Massachusetts, and I wanted to go up and hear her, but Father O'Connor had gone up to hear her, Father O'Connor, Catholic priest, was the jazz priest, a very close friend, a man I loved dearly, and he says, "Don't go, George." She had just gone so down in those few weeks, and after she finished in Lowell, she went in the hospital, and that was it. Jo Reed: Tell me about the Newport Jazz Festival. How did it come into being? George Wein: Well, one night a woman from Newport, Elaine Lorillard came in with a professor from Boston University. And she was auditing some classes at Boston University, and the professor, Donald Borne was a friend of mine. And so he introduced me, and Elaine was saying that, "Newport is dull in the summer," and they tried something the year before with the Boston Symphony or the New York Philharmonic, I guess, and they'd lost a lot of money, and maybe they could do something with jazz. So Donald Borne says, "Why don't you ask George to do something with jazz?" And so she said, "Well, I'll come back with my husband." So she came back with her husband in three nights and I couldn't believe it because people are always saying, "We'll come back and talk about it." And they said, "Yeah, we'd like to do something." And I said, "Well, let me think about it." And I went home and I thought about, you know Tanglewood has a music festival, a classical music festival, why can't there be a jazz festival? And I went back and told them, and I gave them an estimated budget, a concept. And Louis authorized me to draw 20,000 dollars out of his bank in Newport, and then they went to Capri for their vacation, left town. And it just happened. We broke even the first year, and never had to use that 20 thousand dollars, never had to draw on it, and in the business for the rest of my life. Jo Reed: We're so used to jazz festivals now that I think it's hard to remember that you were really the first to produce an outdoor, multi-day, multi-venue jazz festival. George Wein: Well, I received that APAP Award which was for changing the directions in which people listened to music in the summer. And I was very appreciative of that award, because when we were doing things, you didn't realize we were pioneers. We weren't going by a book; we were writing the book as we went along. Nobody had ever done these outdoor festivals the way we did them, and learning about sound, learning about how to work with communities, learning all the little things that are par for the course now. And we had to create them as we went along. We learned about outdoor sound. We learned about crowd control. And one thing led to another, and then we did the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. I started the Newport Folk Festival. And next thing I know I had a nonprofit board. Pete Seeger came up with the idea of all the musicians, no matter whether they're Bob Dylan or Joan Baez or Georgia Sea Island Singers, everybody got 50 dollars a night. We had, seven or eight of the greatest music events that ever happened. They weren't jazz, they were folk. But they were just fantastic events. So all of these things are part of my life. And then out of the folk and jazz festivals is what came the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. Jo Reed: Which is huge. George Wein: Yeah, because I just combined the two together. So those are a few of the things I've done in my life that have had meaning. That's why I was appreciative of the award because, as you say, people almost forget-- they don't almost forget, they forget. George Wein: So it's nice to be recognized but the point is, it's all nice to be part of history, but now I'm doing one of the more important things I've done in my life, and that's turning Newport back into a nonprofit, because when I went back there in 1962, I had to make it a business to keep it alive. But now I turned it back into nonprofit just last year. Where the mission is that jazz is an ever-evolving music, and if we don't recognize this evolution of the music and the directions that young people are taking, the music is going to die. And we have to give them a stage, and we have to try to build them the image and the reputations of the really talented young players. And so Newport, out of 30 artists, 20 of them will be young, relatively unknown musicians. And it's a big risk on our part, because we're not using any big-name performers to sell the tickets. We're selling a festival. We're selling a festival of jazz and what is happening today. But all jazz, not crossover music. And I'm very excited about it because I'm getting to know all the young musicians. I have them up here for lunch, and we talk about Newport and what it means, and hope that they feel it's important to their career. And the more important they feel Newport is, then the more important Newport is. And I was very pleased to see that we were number one in the Jazz Times poll for the best festival this year. Jo Reed: Congratulations. George Wein: So that made me feel good again to be back on top. But that's because of what we're doing. And we have the advantage of the fact that it's not a business, and my board is willing to go along with me, and the fact that I'm putting in money along with them. The profit is not the direction, just putting on great festivals is the direction we're going in. Jo Reed: 1956, the great Duke Ellington performance at Newport. Gave Ellington's career a huge boost. It got him on the cover of Time magazine. George Wein: That shows a why the passion for jazz is important. I was very passionate. To me, Duke Ellington was a god. I did not know that Duke Ellington's career was on the wane. I didn't have the slightest idea. To me he was Duke Ellington. I didn't know that he was having career problems, and I just treated him as the star of stars. And he called me two nights before the festival, actually it was when the festival had started, and said, "What's happening up at Newport?" This was a Thursday. I says, "Lot of people coming. Lot of press are going to be"-- I said, "What are you going to play?" He says, "Well, we'll do the medley, do--" I said, "No, you better not do that. You better come in her swinging," I said, "because everybody's going to be here, and you better come in with something happening." And I guess that's when he went in and he came up with the "Reminiscing in Tempo" with Paul Gonzalez. And once he started to play, he saw the crowd start dancing, and he kept it going. And the excitement just kept regenerating itself. More and more and more and more and more and they kept playing, 27 choruses. [Musical Break - Duke Ellington's "Reminiscing in Tempo"] George Wein: The first happening at a jazz festival. It was a real happening. Duke used to say ever after that, "I was born at Newport in 1956." Jo Reed: You had said that you'd never seen a crowd that enthusiastic. George Wein: At that point, everybody got up out of their seats and started to dance. The crowd was well behaved though, but Duke knew how to treat the crowd. When he did finish, finally, I wanted him to come off the stage. He wasn't about to come off the stage. This was his moment. But he had Johnny Hodges play a slow ballad, and the crowd just settled down. And boy, did I learn from that. Jo Reed: You were very close with Duke Ellington. George Wein: I had the opportunity to work with him. There's a book, "Everyday in the life of Duke Ellington" And I went over that book-- so they got the booking sheets I think from Associated Booking-- and it listed every event he did in the last 20 years of his life. I was involved with Duke on 365 different occasions. So in other words, one-twentieth of his life, his last 20 years, I was directly involved with. And we became good friends, and we trusted each other, which means he trusted me, because I always trusted him. He was somebody you could trust implicitly from a performing point of view. And it was never any possibility that Duke might not perform because something wasn't going right. He would say, "I don't care what the problems are or what the-- if I get paid or I don't get paid, or that one thing is wrong or another thing is wrong. I'm going to do my program because people have paid to come see me, and I'm never going to let them down." A lot of other artists didn't feel that way. So if Norman Granz would bring in, if the piano wasn't just right for Oscar Peterson, he'd cancel the concert. Or if something was wrong, he would not do it. I would never do that with an artist. To me, you straighten out the problems, then you don't work with the guy again, or you just whatever it is. But there's a dedication to the music that is absolutely necessary. And as a performer, I'm the same way. Because when I was a kid playing in some of the joints, sometimes the pianos were a half-tone out of tune. And I had to play everything transcribed in the wrong key, and I wasn't that good. But you struggle through and you do it. Hey, what's the difference? Jo Reed: Why do you think the Newport Jazz Festival, the granddaddy of all festivals, why do you think that festival originally was so successful? George Wein: A lot of these things relate to destination. I always wanted to go to Newport, I'd never been there. I'd read about the summer cottages, the breakers, and the elms. And there was a fascination about going there, and I never had driven down there. It was a little out of the way. It was 70 miles from Boston, and it was near Providence. But there was one bridge, and the other side you had to take a ferry. There were no trains. No planes went to Newport. And you had, as I said, pay a toll on a bridge, so you had to take a ferry. You couldn't get to the island, you know, no way to get there. So I said, "This will be a good place for a jazz festival." Jo Reed: Also one thing that unique about Newport is that you had musicians playing different types of jazz. It wasn't a festival of one particular type of music. George Wein: Well, back in the '50s there was this division in jazz between the swing era and the swing musicians, and this new music that Dizzy and Charlie Parker had created, bebop and modern jazz, and Lennie Tristano. And there was still this strong fight. And in the very first festival, I put Eddie Condon, who represented Chicago jazz, and Gene Krupa and Billie Holiday, the swinger, Teddy Wilson, on the same program with Dizzy Gillespie and Lennie Tristano and Lee Konitz. It was the first time people had done that, of just say jazz and people, I'd say "Jazz is a music from J to Z." I always had that feeling. I didn't realize we were pioneering. I knew what my club was. I had many different attractions in the club. One week it would be modern, the next week might be Lee Wiley with Bobby Hackett, and then the next week might be Count Basie's and then Art Blakey and Horace Silver. So I knew all the musicians. I liked it all, and I was getting to know and learn more about music all the time. Jo Reed: Finally, three wishes for jazz, what would they be? George Wein: It's tough to ask me that, because I've realized most of my hopes and wishes, and I keep thinking of new things. So now I just want Newport to continue after I'm gone.I have no family particularly, and whatever I have, I am going to leave towards an endowment for the festival to continue. And if that endowment is matched by my board and by friends, the festival will go on forever. At least for the next 20 or 30 years. That's the main wish that I have. The young people want to play the music. There are thousands of young people coming out of schools. I mean, this is what people dreamed of, to making jazz part of the educational system. It is part of the educational system. And I think remarkable things are going to happen. But my wish is very personal, that Newport continue after I'm gone. Jo Reed: George, thank you so much. And thank you for everything you've done for jazz. George Wein: Well, thank you. Jo Reed: That was the legendary Jazz Impresario and 2005 NEA Jazz Master, George Wein. You've been listening to Art Works, produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor. The following excerpts were used courtesy of Sony Music Entertainment: "White Heat" written by Will Hudson and performed by the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra, from "Lunceford Special," Jimmie Lunceford, 1939-1940. Used by permission of EMI Mills Music Inc (ASCAP) "When It’s Sleepy Time Down South" written by Clarence Muse, Leon Rene and Otis Rene, from "Louis Armstrong: Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man," 1923-1934. Used by permission of Shapiro Bernstein Co & Inc. (ASCAP), 35% EMI Mills Music Inc (ASCAP), and 1.667% Colgems-EMI Music Inc (ASCAP) "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue" and "I've Got it Bad (and that ain't good)" both written by Duke Ellington and performed by Duke Ellington and his Orchestra from Ellington at Newport, 1956. Used by permission of EMI Mills Music Inc (ASCAP) I've Got it Bad (And That Ain't Good) written by Duke Ellington and performed by Duke Ellington and his Orchestra from Ellington at Newport, 1956. Used by permission of Sony ATV Harmony (ASCAP) The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. And now you can subscribe to Art Works at iTunes U -- just click on the iTunes link on our podcast page. Next week, air force veteran and poet Lynn Hill. To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.A conversation with George Wein, the man who launched the first outdoor jazz festival in the US--the legendary Newport Jazz Festival.