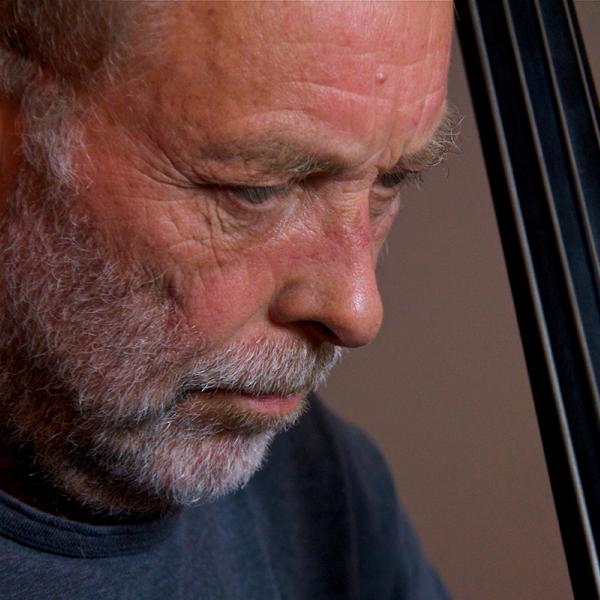

Everett McCorvey

Transcript of conversation with Everett McCorvey

Jo Reed: That was the voice of tenor Everett McCorvey singing La Danza by Gioachimo Rossini. Welcome to Art Works – the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nations great artists to explore how art works. I'm your host, Josephine Reed. Everett McCorvey isn't just a first-rate operatic tenor, he's also the Professor of Voice and director of Opera at the University of Kentucky as well as the founder and music director of the American Spiritual Ensemble. And in case that isn't busy enough Everett is also vice-chairman of the Kentucky Arts Council for the Commonwealth of Kentucky and serves on the board of the National Association of State Arts Agencies. Somehow, in the midst of his very hectic schedule, Everett McCorvey found the time to talk to me about opera and African-American spirituals. I began our conversation by asking what first drew him to music.

Everett McCorvey: What drew me to music? Well, when I was in, when I was about second grade, I guess. I lived in Montgomery, Alabama. And I grew up in Montgomery, Alabama during the Civil Rights Movement. And it was before integration. And so most of the African-American students who wanted to attend college went to an African-American college of some sort where there is one in Alabama, in Montgomery, called Alabama State. At that time Alabama State Teacher's College. And we used to keep boys who went to Alabama State. We had rooms in the back of our house. We had three rooms and we had twin beds in each room; and we kept six young men who were in school, undergraduate school at Alabama State; which was the custom in a lot of these cities because they had dormitories, but not many. And it was a community effort for the people who were going, attempting to go to college. Well, one of the young men played the trumpet. And he was in the band at Alabama State, and I remember coming home one day. And he was practicing the trumpet in his room. And I thought it was the sweetest music I had ever heard in my life. And so I talked to my dad, and I said; Dad, I would really love to play that instrument, and learn how to play it. And so my dad said, "okay." And so he took me up to the local black high school, which happened to be about a block from our home. I talked to the band director there; scheduled a time for me to have a lesson on a trumpet. And he took me down to the store, and we rented a trumpet. And so, I guess about a week later I went up from my trumpet lesson, and it was a life changing experience for both of us. And I'll tell you why. I had a trumpet lesson with the band director. And he died the next day <laughs> That's why I say it's life changing.

Reed: You can't make that up.

Everett McCorvey: No, you can't make that up. And, but I still love the trumpet. And so in the third grade, I was in the high school band. And I was the only elementary school kid in the high school playing trumpet. And so that, that was the start of my relationship with music. I had sung in choir, and in church, and done things like that. But when I heard that trumpet, I thought that's beautiful. And I wanted to be a part of that.

Reed: But you moved to voice?

Everett McCorvey: Yes, I did. When I sang in the choir at my church and when I went to college. By the time I went to college I changed from trumpet to baritone horn. And I auditioned at the University of Alabama on my baritone horn. And I also said; and by the way I sing. And the man who heard my audition, my singing audition was the voice teacher for Jim Neighbors. And I don't remember Jim Neighbors' Gomer Pyle. And his name was Bill Stephens. I'll never forget it. Anyway, he talked me into pursuing a career as a singer. He said, "Son, baritone players are a dime a dozen, but singers." And so I decided to go to the University of Alabama and major in Voice. And that started the journey.

Reed: And it's a journey that has taken so many different roads for you Everett. I was, I was–– you, in preparing for this interview. I looked at my colleague and I said; I don't see how he sleeps?

Everett McCorvey: Well, I have a lot of different activities going on and I love them all. I'm currently involved in the project of I'm the Executive Producer of the opening and closing ceremonies of the All Tech FEI World Equestrian Games, which is the largest equestrian event ever to happen in this country. And so it's a busy time right now.

Reed: It sure is. You still perform.

Everett McCorvey: Yes, I do.

Reed: How did you add teaching and then administering a very prestigious musical program at a university?

Everett McCorvey: Yes, well, it's all having a great staff. And I think that's where it starts. I came to the university to teach voice, actually.

Reed: And that was back in '91?

Everett McCorvey: That was in 1991. And–– but the director of the school at the time said, "I would like to have an international program in voice." And so I made some suggestions in terms of how we might do that. And one of them was that we had to have a larger staff. And we had to produce quality opera. And so, in '91, I took over the opera program around 1994. And we had a $20,000 loan that we had to give back to the University at the end of each year to produce opera. And we'll fast forward now a few years. And now our endowment for opera is about $5 million. And our budget for opera is about $1 million a year, which is amazing for a public land grant institution. Lexington is a wonderful place to live. They really support the arts. And we've been, we've had the great fortune of having some generous donors to endow our program. And we've been able to create quite an exciting program for opera.

Reed: Well, I want to talk about that because with all due respect to Lexington. I think of horses. I think of basketball.

Everett McCorvey: That's it–– and Bourbon. <laughs>

Reed: And Bourbon. And I'm, I am completely owning that that's my ignorance. But you were also pretty smart in looking at Kentucky, and Lexington's love of sports. And thinking how can I model this? Talk about that.

Everett McCorvey: Well that's exactly right. One of the first things I did when I came to Lexington was the president at the time appointed me to the athletic board. And I joined the athletic board, and I really learned so much about how business is done at a university. And the athletic board was its own entity. And it worked within the university. And so that gave me the idea that I should create a society, a group, that's similar to the athletic association. So I was on that board for I don't know, four or five years, and. But during the time I decided to create a board called the Lexington Opera Society. And there was a small opera company in town called Opera of Central Kentucky. And they weren't doing very well, and they were really surviving pretty much by the work that we were doing at the university, using our staff, our students. And so I went to the board and I said; why don't we collaborate and figure out how we can take the best of Opera Central Kentucky has and the best of what U.K. Opera offers, and put it together. Well, I found a lot of resistance. But people eventually decided to do that. And I changed the name. I created the Lexington Opera Society. And so, it's a 501(c)3 organization. And it does not produce opera. But what it does is it promotes opera in Central Kentucky primarily through the productions at U.K. Opera Theater. And so this is a 33 member board. I I personally chose the 33 people on the board. They had, they have each year, they give a $1,000.00 to be on the board. And so we had a budget of $33,000.00 to work with. And so this board became the fundraiser board, and the "friend raiser" board for the opera program. And so it's a town and gown collaboration. They don't make decisions in terms of the productions or anything like that for the opera program. But they are our cheerleaders in the community. And they go out and they help us fundraise. And they help us make people aware. They have–– and so it's probably now. The board is still 33 but we have a Bravo Society that's like the Guild, and that's about a 400 member organization. And so now they help us raise–– gosh, they probably contribute in time and money over $100,000 a year to the cause of the opera program. And so that's what's helped us to create the awareness of opera in the community. I just follow the athletic tradition. And it worked for athletics, and I felt well, why not make it work for opera. So even at the basketball games we have opera singers sing. And basketball is definitely the religion. And yes, we are proud that hopefully we're going to have five first-round draft picks. <laughs> But, we've joined in that model. And so, and so now when there are athletic events our singers sing. When there are large events in the singers–– large events in the city, our singers participate. I'm on a lot of boards in the city. And I must say I learned that from Charles Nelson Riley who the opera fans will know was a great opera fan when he was alive. And one of my jobs through the NEA was to….I went around the country doing on site evaluations for Young Artists programs. And one of my on site evaluations was in Chicago at the Chicago Lyric Opera. When, and that day that I was there Charles Nelson Riley happened to be there working with the opera singers. And something he said really changed my life. He said, "If it's important to you, then it's your job to make sure that it's important to them, to everybody." And he was telling that to the opera singers in the Young Artists program. He says, "Make it important. If it's important to you then make it your job to make it important to them." And so that's something that I do in Lexington when I'm in–– I'm on–– gosh, five or six of the boards. And I find out what they're doing, and I get involved in what they're doing, and then I encourage them to get involved in what I'm doing.

Reed: So, it's a reciprocal relationship.

Everett McCorvey: It's a reciprocal, absolutely.

Reed: And underline relationship.

Everett McCorvey: Absolutely. It's a reciprocal relationship. And it is a relationship; and so, I don't go. I go first and find–– I go to them first. And I engage in their activity. And then, so it's very easy for them then to engage in my activity because I've already participated in theirs. And so it's a great relationship that we've built in the city. And it's really, it's quite exciting. And the entire city has taken ownership of the program.

Reed: Well, you had a world premiere there, River of Time.

Everett McCorvey: That's right. We've had a–– during the Abraham Lincoln Celebration of course Lincoln was from Kentucky. And we felt it important to make sure that Kentucky celebrated Lincoln along with the rest of the nation. And so we had several major Lincoln events. One was a premiere of an opera, River of Time. The boyhood life of Abraham Lincoln, and the influences that made him the man that he became–– very successful. We also brought a very big Lincoln program to the Kennedy Center, called Our Lincoln. And it was, we brought about 350 musicians from Lexington, and had a huge celebration at the Kennedy Center. And I'm very happy to say that my professional group, the American Spiritual Ensemble gave a citywide concert in Gettysburg on Abraham Lincoln's actual 200th birthday. And that was really exciting.

Reed: Can we talk very briefly about the formation of the American Spiritual Ensemble?

Everett McCorvey: Yes.

Reed: And I want to begin by asking you what the difference is between spirituals and gospel? Because it's often confused.

Everett McCorvey: And thank you for recognizing that difference because a lot of people, even in this country and in other countries don't recognize the difference. But there is a difference. The spirituals are the folk songs of the American negro slaves. And from the spirituals, many sorts of music and art forms grew. But when the slaves came over they were not allowed to bring their instruments. They only had their voices. And so when they would work in the fields, or when they would meet privately, they would sing. And the slave masters did allow them in some cases to go to their churches, and sit in the back, or whatever. Because they had to assimilate the ways of their slave masters. And so they took the music, the rhythms of their culture, and combined it with the music that they heard in America. And they created this new music called the spirituals. And so from spirituals grew all sorts of music. And you, when you think of gospel music, really you have to go to the 20th century in the 1930s and ‘40s, Thomas Dorsey, who is in many instances is called the Father of gospel music. Thomas Dorsey was a, he was a blues musician. He played in the clubs and he played the more popular music. And then at one point he was asked to play in church. And he took some of the music that he had been playing in the clubs and brought it into the church. Well, they –– the church members called it the devil's music. They didn't like it at all. All these blues chords, and these popular chords, and then they would put in religious text. And they didn't like it at all. And so, but the minister noticed that all of a sudden the young people were starting to come back to church. And so the minister sort of liked it. And so really gospel music grew out of the blues and the spiritual tradition that had already been established. But the spirituals were the mother music. They, it's, the spirituals is where it all started. And then the late 1800's the African-Americans who wanted to learn how to write this music down of course could not go to colleges. They couldn't go to conservatories. And so it was really Antonin Dvorak who came over in 1890 to head a music school in Washington. It's no longer there. But Dvorak came over to head this music school. He was one of the first people to allow African-Americans, negroes, to attend this conservatory. And Dvorak wrote his probably his most famous piece, The New World Symphony when he was in this country. And he said as, in the preface to the New World Symphony, he says, "In the music of the negroes and the Native Americans you have all that is needed to create an entirely new school of music." And that was the first time that the melodies of the Negroes were recognized. And it took a European composer coming over to recognize these melodies. And his most famous student was a man by the name of Henry T. Burley. And Henry Burley was was a base baritone, singer but they learned from each other. Burley taught him all of the wonderful melodies of the Negro slaves. And Dvorjak taught Burley how to write all of this down. So that then it could be there for posterity.

Reed: Let me ask you. Because I think of the music of the Civil Rights era.

Everett McCorvey: Yes, spirituals.

Reed: As spirituals.

Everett McCorvey: Spirituals, yes. Yes, those are–– and that was the other thing about spirituals that was so amazing is that they have the ability to sort of reinvent themselves as the times warranted it. And so you have the spirituals that brought people through slavery. Then you have the spirituals that brought people through the Civil Rights Movement. You had spirituals being sung even during the Obama elections. And if you look, if you go back and listen to the prayer of Joseph Lowery that was at the end of the Obama Inauguration, they are all spirituals. And it was amazing how he brought it all front and center by repeating a prayer that was all of these spirituals. And I happen to be at the inauguration. And I'm telling you when I heard him do that it was just, it was something that I'll never forget.

Reed: Yes. I was very pleased that Joseph Lowery was honored in that way.

Everett McCorvey: Yes, that's exactly right.

Reed: And used the platform <inaudible>.

Everett McCorvey: And used the platform so well; and to celebrate these wonderful melodies.

Reed: So you formed an Ensemble. How many years, 15?

Everett McCorvey: Fifteen years ago; and the American Spiritual Ensemble, they are comprised of all opera singers. And they live all over the country. And when it's time to perform they all fly into Lexington. And we rehearse there. And then we go to parts unknown. And basically, when I started the group 15 years ago. I just called 15, 20, of my friends and said; hey, I think I'm going to start a group to celebrate the Negro spirituals. Because I realize that people were not aware of the difference between spirituals and gospel music. And that these great Negro melodies were being lost and being clumped into a larger category of gospel music when they had their own and deserved their own identity. And so we started the group, and I have been amazed and honored at the number of singers that have traveled through our group in the 15 years: Lawrence Brownlee, Angela Brown, Karen Slack [ph?]. Many of the performers, African-American performers who were on the world stage today, many of them came through the American Spiritual Ensemble on their way up. And Angela Brown for instance, still calls me and say, "Okay, I'm ready whenever I'm available, I'd love to sing with the group." And we travel all over the world. I mean, it's been very exciting to celebrate these songs, and to help keep this tradition alive.

Q: Well let me ask you. And in some ways this is a completely unfair question. But, you sing opera. You sing spirituals. What are the differences and what are the similarities?

Everett McCorvey: Well see, that's a very good question. Because if you think about singing and the history of singing, everyone who wanted to sing took voice. And if you think about amplified sound, that's another 20th century phenomenon. And so before then people had to study voice if they were in any sort of career that required that there, that their voice needed to project; ministers, lawyers, professional speakers. And so with the advent of the microphone, then what happened is that people lost that ability to do that. But when the spirituals were being sung there was no microphone. And so the fact that these opera singers who have trained their voices and are able to sing it with no microphone are singing these spirituals is just an amazing experience.

Amen up and hot

Reed: You hear a lot of singers. A lot of young singers, particularly.

Everett McCorvey: Yes, I do.

Reed: What is, what do you think is important in training a young voice. Or, in opening up a young voice to opera?

Everett McCorvey: Yes. I think probably what happens in young singers, what we have to work on a lot is helping them to understand their bodies. Learning how to breathe. I call them a singing athletes. They are professional athletes. Their area just happens to be singing. But they have to learn their bodies, and how to breathe, and how to use their bodies to learn how to project the sound. That's a biggie. The other thing that we concentrate a lot on for young singers is helping them to be good musicians. And so it's important, especially for young people if they, if parents see that they have a child that may have an aptitude for singing. It would be great to get that child in violin lessons to help them to train their ear. That's the instrument that I recommend the most. Also help the student to get into piano. Piano is the mother instrument. And every performing artist has a relationship of some with the piano. And so we get them started there so that then when they come to college they have some of the tools that they'll need to be able to grow as a singer and as a musician. Something that I do that is very important to me is I talk about training the complete singer, the complete artist. And what does that mean? That means in addition to being a good singer, and a good musician, you must be a good colleague. And you have to be a giving colleague. Not a taker but a giver. And so, people who are not givers don't do well at the University of Kentucky.

Reed: You know, it's interesting that you say that because my next question to you was going to be the University of Kentucky has not just such a well regarded school. But it's so companionable.

Everett McCorvey: Yes. And that's by design. We feel that we are creating citizens, contributing citizens to society. And how can we be a giving, contributing citizen to society. And our medium happens to be opera and vocal music. But we want people who are going to give to their community, not just take from their community. And so in that sense when we bring people to the University of Kentucky we train the entire person. And yes, you can have a tremendous talent and be a tremendous citizen and a giver. You don't have to be a taker. And that's something that's a, that's something that's really important to me. And I think that it has helped me in my career. And I want to train other young people as they come in and are trained, and moved to cities around the world that they get involved in their communities so that our art form won't die. And won't be stuck off in some little corner because we're not contributing in the rest of the fabric of the city and the community. But when we get front and center, and contribute to the fabric of the community, then when we ask them to come to our events, they will do so gladly and willingly.

Reed: That's so wise. It's so obvious. It's so true. Everett, it was such a pleasure.

Everett McCorvey: Well, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me…

Reed: On the contrary, thank you for taking the time to talk to me. I really enjoyed it. Thank you.

Everett McCorvey: Well, thank you.

Reed: That was Tenor, Director of Opera at the University of Kentucky and music director of the American Spiritual Ensemble, Everett McCorvey. You've been listening to Artworks produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the assistant producer.

We opened the program with La Danza by Gioachimo Rossini, sung by Everett McCorvey.

And we heard the traditional spiritual, "Amen", sung by Everett McCorvey and the American Spiritual Ensemble. The ArtWorks podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. Next week, documentary film-maker, Ken Burns

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Additional credit –

The performance of "La Danza" was taken from a live performance of the UK Opera Theatre performance of DIE FLEDERMAUS from the party scene in Act II. The date of the performance is March 13, 2010 at the Lexington Opera House in Lexington, Kentucky. UK Orchestra under the direction of John Nardolillo.

"Amen," from the CD Ol' Time Religion (2001), arranged by Robert De Cormier, used by permission and courtesy of Everett McCorvery and the American Spiritual Ensemble.

Operatic tenor Everett McCorvey talks about how he was drawn into the music, how he helped build the opera program at University of Kentucky, and the difference between spirituals and gospel, among other topics. [26:17]