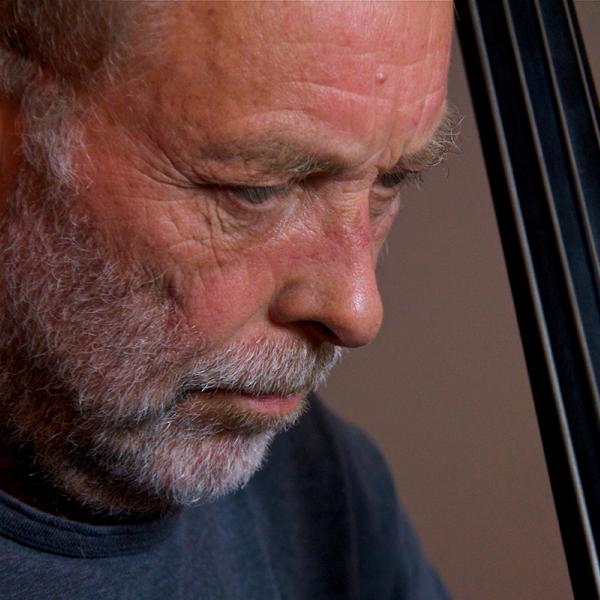

Andy Statman

Transcript of conversation with Andy Statman: Part Two

Old Brooklyn hot, under

Jo Reed: That was musician and 2012 National Heritage Fellow, Andy Statman playing "Old Brooklyn." it's from his latest cd, Old Brooklyn.

Welcome to Art Works the program that goes behind the scenes with some of the nation's great artists to explore how art works. I'm your host, Josephine Reed.

Last week, we heard the first of a two-part interview with Klezmer clarinetist, mandolin-player, and composer Andy Statman. Andt ia receiving the 2012 National Heritage Award for his klezmer music. Klezmer music is the traditional instrumental music of the Jews of Eastern Europe; Andy defines it as Hasidic vocal music played instrumentally. Andy Statman is one of the people responsible for its revival. But as we learned in last week's podcast, it's impossible to put Andy Statman in any neat musical box. He cuts an extremely wide musical path, he followed his initial absorption into bluegrass and the mandolin with a fascination with jazz and the saxophone. Never content to sit still musically, Statman then took up the clarinet and studied Greek, Albanian, and Azerbaijani music. Yet, Statman doesn't drop one musical style for another, he just keeps adding to his stockpot of knowledge and sensibility, moving effortlessly from genre to another. For example, he followed his pathbreaking album Jewish Klezmer Music, with Flatbush Waltz, a mandolin masterpiece of post-bebop jazz improvisations and ethnically-inspired original compositions. However, in his last CD, Old Brooklyn, however, Andy Statman presents a real marriage of all his musical styles. You'll hear strains of bluegrass, klezmer, jazz and blues coming together in this brilliant work.

Statman has released 20 of his own recordings and has performed on close to 100 others. He's worked with the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, Ricky Skaggs, Béla Fleck, Itzhak Perlman, and many others. He fronts the Andy Statman Trio which plays weekly gigs around NYC.

Last week, we heard about and sampled Andy's bluegrass and mandolin. He spoke about the importance of jazz, particularly Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and Albert Ayler to his own musical evolution.

But by 1975, Andy Statman had begun thinking of his own Jewish musical roots. We pick up the interview with Andy meeting the man who would become his mentor: the legendary klezmer clarinetist and NEA National Heritage Fellow, Dave Tarras.

Andy Statman: I looked up Dave Tarras in the union book and uh.. went out to see him, and I had transcribed some of his melodies on the saxophone and mandolin, and at that point I didn't have a clarinet. He was sort of amazed that not only a person much younger than him would be interested in this music, but that I actually did this. And we sort of hit it off. I became like a houseboy there as well. I wanted to play on the Albert System clarinet, which is what the old-timers played, and you know, he gave me clarinets, and, you know he had no real way of teaching, and basically I just slowed down his recordings and- of other people. And what I would do is I'd go over there, and his wife would make us some tea and cookies, and stuff like that, and we'd talk. Maybe he'd want me to take him out for a haircut or get something for him, and then, you know, we'd sit around and talk a little bit. And then he'd take out his clarinet and play for me for about an hour. I'd ask him some questions, and I'd say, "Dave, would you do this this way?" And he'd say, "No, never this way, only this way." And you know, what we call klezmer music, there's like an oral law of how to interpret songs when and how to use ornamentations, and it's very logical, but it can only be really learned through osmosis. It's something that can't really be written down. And so he was really helpful, and he had very strict feelings about a lot of this stuff, and very strong opinions about a lot of it. And we became very close. I know that he'd been a very tough character in the music business, but he was, too, sort of like a, you know, another grandfather to me. And you know, he sort wanted me to carry on for him, but not to be him. You know, he wants me to carry on for him in my own way.

Music up and hot.

Andy Statman: He understood musicians are individuals, and- and the way to carry on a legacy is- is not to be a carbon copy of someone, but for that, you know, to take what that person taught you and move on from it. And that's probably the way he learned, also, from his uncles, and other people who we said were very great players.

Jo Reed: Well, don't you think that's the only way any art stays vibrant; it has to move into the next generation, and then it gets reconfigured in some ways.

Andy Statman: Yeah. I'm simultaneously a purist and expansive at the sa⦠I mean, there are people who I've heard who would make records and do Django Reinhart solos note for note, or Bill Monroe solos, and you can say, you know, "Why are they doing it? It's not as good as, what was improvised." On the other hand, though, they are keeping a certain aesthetic alive. They're really true to a certain aesthetic, and they're trying to keep the beauty of that thing alive. And it's an important thing, âcause you need people who are preservationists so to speak. In essence, if you want to be an innovator in a style, you need to preservationist also, because until you can speak the stylistic language fluently, you can't really understand how to innovate in the style.

Jo Reed: It's like a jazz musician.

Andy Statman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: If you don't know how to play the instrument, you're not going to be able to improvise. You have to know that instrument.

Andy Statman: You have to know the instrument, but you also have to know the language.

Jo Reed: Right.

Andy Statman: So I'm sure it's still possible to innovate, say, in what they call "traditional jazz," but, you have to learn the language. I mean, they're all equally valid. One is not better than the other. They're all saying different things in different ways, you know, because one is older doesn't mean that it's less valid than something newer. The timeline as seen in terms of progression from not as good or sophisticated to better, is really a fallacy, because it really has to do with the power of expression and the ideas being expressed, and how they're being expressed. So with Dave, you know, he said to me, "You know, there'll never be another Dave Tarras," he says. "But, you know, then, there shouldn't be, you know? He's Dave Tarras." And he said, "'Cause you have a lot of heart, you'll be able to carry this on." Soâ¦

Jo Reed: And he left you his clarinets...

Andy Statman: Yeah. I used to get grants for him to write music, so I- I'd try to stimulate, he was a great composer, grants from the record company. I'd try to get him into writing, and he was a great, great musician, and a very, very aware person. And as it turned out, I found out we were distantly related. <laughs> Distant, but definitely related, you know?

Jo Reed: That's funny.

Andy Statman: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Jo Reed: So, what was your first recording of klezmer music?

Andy Statman: âKay, so the first recording I did was with Zev Feldman. And Zev back then was very traditionally oriented, and what we were looking to do was to try and recreate, you know, in our own way, what this music might've sounded like 70 years earlier, you know, particularly if had been in Europe. And so for me, I had to have some stylistic blinders put on because I would hear things. I would see the similarities between Junior Walker and whose studying- playing I studied in, and Dave Tarras. I had to keep it in within certain boundaries, both on the clarinet and on the mandolin. There really wasn't a mandolin style of this music. Based on my understanding of the ornamentation through the clarinet playing, I developed a mandolin style to go with it.

Up and hot

We were doing this just to, you know, really for ourselves, you know? We weren't looking to revive anything. We made a decision. You know, I said, "I really want to do this. No one-- this music is not being played, and we should just try and keep it alive for ourselves." You know, I never expected that it would become the focal point for me for a number of years. And that was also partially by the economics of the business because the gigs I got, you know, klezmer music paid better and were better conditions.

Jo Reed: Plus side.

Andy Statman: Yeah, than- than- than playing, uhm.. you know, in bars with rock-and-roll bands or bluegrass bands or whatever. You know, I was still playing in a lot of different bands at that time.

Jo Reed: I knew you were playing in funk bands.

Andy Statman: Yeah, yeah. That was fun. At the same time I was doing the record with Zev Feldman I was doing this record called Flatbush Waltz, which was just a whole other thing.

Jo Reed: Well, describe Flatbush Waltz. That's a very important early record for you.

Flatbush Waltz under

Andy Statman: To make a long story short, I started developing my own music, and I was very interested in doing something that just reflected all these different influences that I had studied. So it was, in a way, it was a bit of a world music record. There's stuff in there from _____ music. There's the song Flatbush Waltz I wrote, which is a combination of a traditional Jewish song and a Bill Monroe song, and it has an introduction that- that owes a lot to traditional or I say classical Azerbaijani music. Then there were just these things that owe a lot to Eric Dolphy and Mingus compositions on there.

Flatbush Waltz up and hot

Jo Reed: When did you start composing, Andy? Was it with Flatbush Waltz?

Andy Statman: No. I started composing when I was about 16, started writing songs. With Country Cooking, I got sort of reinspired to do it, âcause all these people were writing songs, and Breakfast Special a bit. And then around the time I was doing the thing with Zev, I started getting and composing a lot more, Â just started writing a lot. Goes through stages, and it's just another skill I picked up, you know?

Jo Reed: <laughs> Okay, here come the ignorant questions.

Andy Statman: Yeah, yeah.

Jo Reed: I hope you're ready for them.

Andy Statman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: And that is, moving from the saxophone to the clarinet, what's the difference, in terms of expression and what you can do with them, and...?

Andy Statman: Probably because I played mandolin, I loved the wooden sound of a clarinet, and uh.. I love the feeling of a clarinet. And as great as the saxophone is, there are certain emotional areas it can't cover as well as the clarinet, you know, particularly for me the old Albert system clarinets, and the music that was developed on them. They're just very soulful instruments very beautiful instruments you know, the- the tone and- and the music that's been played on them. They can take a lot of the beautiful things that a violin does, but then do whole other things with it. And terms of playing free music on it, they're great, also. I mean, like if you have a tenor saxophone, then you have much more-- it's deep. You have all these other overtones you can deal with, so you can get a broader type of palette. But there's something about wind instruments that I really like, although I love the saxophone. But probably back in the nineties, I just couldn't do everything, and I just sort of you know, realized that I'm, you know, I sort of have to limit. So I was mainly into the clarinet then and that's sort of what I did, and keeping the mandolin going. And I go through different phases where, you know, I'm more into one instrument than the other, so...

Jo Reed: When you're composing, do you, as you're composing, do you think, "Ah, mandolin; ah, clarinet," or when you're done, you weigh it and make a decision then?

Andy Statman: That happens sometimes, but composing is the type of thing where you have to turn it on, and then you have to turn it off. If I'm writing for a records are very much like menus, and you need to have a variety of, say, different types of food: you know, fish, meat, chicken, desserts that-- you know, so it's like you know, you write for specific types of melodies expressing certain types of feelings. Well, you need this type of song, you want this type of song, so you write going by that feeling. And I find that once I start writing, then whenever I pick up an instrument, I just start writing. So, like, I know like when I'm recording records, I'll wake up in the morning, have breakfast, and as I'm about to go to the studio, a song pops into my head, and I say, "Yeah, we need one of these," and I'll write it in the- in the taxi on the way to the studio, and then we'll record. The problem with writing is that it then- it- for me, is it can take over my whole musical thing, and I need to practice. So at some point, I have to stop writing and not follow the ideas, in terms of songs, and it takes a day or two, and then just get back into practicing. And then when I need to write, I sort of have to turn that on again, it's not difficult-- and then just let it go. But it interferes with my practicing. So it's a uh.. but, you know, professional songwriters, you know, a lot of them nine to five, you know, they get up, go to the office, and they write all day, and they don't have to turn it off. I guess they turn it off when they go home, <laughs> but...

Jo Reed: <laughs> This is jumping around a little bit, but you've been working-- you have a trio.

Andy Statman: Right.

Jo Reed: You've been working with a bassist and a...

Andy Statman: Drummer.

Jo Reed: Drummer...

Andy Statman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: For a long time.

Andy Statman: Yeah, about 11 years now.

Jo Reed: Larry Eagle and Jim Whitney.

Andy Statman: And Jim Whitney, yeah.

Jo Reed: And you play at a synagogue twice a week?

Andy Statman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: You said in another interview. I was really intrigued by this. You guys arrive there, and you really don't have a set planned.

Andy Statman: No, no. We just play. A lot of what I do is improvised, So we sort of see what we feel like playing at that moment, and see where it goes, and sometimes we'll do more, depending on the melody or whatever we picked, more little interpretations, we just really expand on them. And it is really just a matter of the moment and how- and how we're feeling.

Jo Reed: So that's a lot of the jazz influence, no? I mean, that's sort of in the jazz part--

Andy Statman: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. See for me, I'm just interested in playing music. I can play traditionally in a number of styles, but that's not what I usually choose to do. I usually just play music and just let the music go where it goes. I have my own aesthetic, and I've developed my own languages in the traditional styles I play, sp I just sort of play. Basically, I'm looking to go on some sort of "exploration" with the music, an emotional exploration, and get it to the point where the music just sort of happens, and I become a, in some ways, almost an observer, as well. It's just another form of talking when you're improvising. And even if you're playing a song where you're not improvising much it's just melody you're still improvising in terms of how you phrase and how you're gonna ornament, so everything really is improvisation.

Jo Reed: What I think is so neat about your music--many things--but the way it somehow combines the Hasidic tradition of music being transcendent, and recognizes that that's what John Coltrane was doing, as well. <laughs>

Andy Statman: Right.

Jo Reed: And it really comes together with you, I think, in a lot of ways.

Andy Statman: Well, I went through a period basically, you know, after after me and Zev got more into academics, I formed my own band, and we were quite successful. But after a while, like with bluegrass. It's just your traditional music can become just another melody to play. What do you do with it? So I had sort of lost my interest in- in- in- in- in playing, you know, the traditional music. And uh.. <clears throat> it's when uhm.. you know, when I became involved in religious community and Hasidic music, it sort of rekindled my interest in in Jewish music, and I realized that, on many levels, this is where the what we call klezmer is coming from, except that it- it, in many ways, it was deeper and even broader, and I realized a lot of the feelings that I was experiencing from klezmer music were really feelings of, you know, Hasidic melodies. So I began wanting to explore a commonality with some of Coltrane's approach to modal music, and the thing is, with traditional music, even though it's very powerful, it's also very fragile. And once you start putting chords to modal melodies, they can very easily distort, they can change the feeling and the idea of what the music is supposed to be. A good example would be if you listen to a lot of Irish music now, they'll take basically modal tunes and put many different chord changes to it. And in some ways, it gives a different emotional color to different parts of the tune, and it's very nice. Â In other ways, it destroys the original intent of the tune, because the chords determine what the melody is saying. That's like someone like Bill Monroe. He would take a fiddle tune and keep it as un-chordy as possible, while in Texas, they put lots of passing tones and things. It's a whole- a whole other different aesthetic, so coming from Bill Monroe. So I was very interested in the way McCoy Tyner's, like, sort of stacked fourths created a very compelling emotional feeling under modal music. So I looked for musicians who could play that and would have some understanding of the traditional Jewish music.

And I always loved Elvin Jones. I used to go see Elvin play all the time, it'd be incredible, and I there's like maybe 10 people in the place. And I was, you know, like, "There's Elvin Jones!" I remember one time he's looking right at me, playing, and I'm saying to myself, you know, "He can't really be looking at me. Is he really looking at"-- you know, and, you know, and I was like, you know, "No, he" I was really scared. but anyway, so Elvin's music had a big influence on me. So I began putting together ensembles to play versions of Hasidic music with this- with these types of approaches, and I guess the most well-known was this record called Between Heaven and Earth. Actually, it was picked by the Times as one of the top ten records of the year. I remember we I got a great drummer, friend of mine I worked with for many years, a guy named Bob Weiner, and Harvey Swartz. Or he calls himself Harvey S., the bassist. And Kenny Werner, piano player, and myself. And I remember getting together with Kenny, you know, the first time I met him, to do this. And, you know, I was there with another of my another of my friends, who's very, Hasidic dressed, you know. So we're playing these things, and I remember he said, "These like stride behind it." And I said, "No, no." I said- I said, "Kenny, look," I said, "When you play, some stacked fourths behind this thing, and be free with them." He was like sort of like, you know, "What a shock," like he goes, "Oh, yeah?" I said, "Yeah." And we really hit it off. And I remember we did this record. In fact, the first cut on the record was a song I discovered by supposedly by the Magad of Mesuresh who was the inheritor, I guess the second generation of the Hasidic movement. Very beautiful song, and it went into a sort of an open improvisation, and it was like really magic.

Maggid up and hot

Andy Statman: We sold out town hall. We did some concerts, and it led to a contract with Sony. And around that time I started doing these things with Perlman. Anywayâ¦

Jo Reed: You and Itzhak Perlman, you mean, made records together?

Andy Statman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: Yeah.

Andy Statman: And touring, an around the end of this time I started exploring this sort of jazz-Hasidic connection. I wound up getting like a weekly gig at the Housing Works, down in downtown. It's a bookstore. And they raise a lot of money for AIDS and things like that. And I started doing it as originally duets, you know, of improvised music with Bob Weiner or some other, you know, different drummers. And at that time, I had started using a pianist named Brendan Dolan, who was a really great traditional Irish musician, but understood how to play in these you know, in these fourths. And the series became successful, and as things evolved I decided I wanted to play a little bluegrass, and then we started two nights, and one night would be Jewish, one night bluegrass. And then I just said, "You know, I just want to mix everything up and- and not make the separation." And after a while, you know, I- you know, I realized that the chords were just limiting me too much. Chords become king, you know? Chords really determine how you play and what you play. And I didn't want to be tied to what the chordal player was playing. <laughs> Hence the trio, which is sometimes a duo and sometimes just solo. And that's how that whole thing came out of these duets I did at the Housing Works.

Up and hot

Jo Reed: In 2006, you had a pair of very different CDs come out, Awakening from Above, which is Hasidic music and East Flatbush Blues, in which you return to bluegrass. That was a very interesting pairing.

Andy Statman: And the East Flatbush Blues was sort of the more American-type thing I'd done in years. The last thing I did was a record called Andy's Ramble. It was a bluegrass record, probably back in the, it was recorded, actually, in the late eighties, came out in the early nineties. So it'd been a long time. It was sort of my reintroduction to the American, <laughs> you know, music world, outside of the, you know, outside of the sort of Jewish-American music scene.

Andy's Ramble up and hot

Andy Statman: You know both records were very well received.

Jo Reed: And Old Brooklyn, which came five years later...?

Andy Statman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: In a way, it seemed like a bridge

Andy Statman: Yeah.

Jo Reed: Between those two CDs.

Andy Statman: Well, what I wanted to do was to just put a record out which just reflects a lot of what I'm doing, and not worry about labels or styles. And the other two records were basically live. These were studio records, and I decided I wanted to bring in some of my friends who, you know, <clears throat> to play with. So we brought in Byron Berline and, you know, and Bruce Molsky, and, you know, John Schull and, you know, Paul Shaffer and Ricky Skaggs, and Bela Fleck.

Jo Reed: Love Bela Fleck.

Andy Statman: A bunch of other people.

Jo Reed: Now, Ricky Skaggs does a very interesting song

Andy Statman: Oh, The Lord Will Provide? Yeah. Yeah, it's powerful. Yeah.

Jo Reed: How did-- was that his idea or your idea? How did...?

Andy Statman: Well, he had once sung it for me over the phone, and  I was very moved by it. And then we did a house concert at his house in Nashville, and as we were leaving, I said, "Ricky, why don't you sing this song for the guys?" And he sang it, and then when he was gonna come to do the session--we were gonna do some duets, maybe some mandolin duets and whatever-- and he- and he said he would-- you know, "Why don't you sing one?" I wanted him to sing a little-known Bill Monroe song called Along About Daybreak. Anyway, when he got to the studio, he said, "You know, I really don't know it that well, and how about if I sing The Lord Will Provide?" I said, "Great." And he had told me he had tried it in different ways, and I think, he called it an Eastern Baptist style. He hadn't had the style down to his liking, although it always sounded great whenever he sang it. Now he felt it was the time. And I said, "Let's just do it with clarinet and voice." And to me, it sounds like some old field-recording from somewhere.

The Lord Will Provide up and hot

Andy Statman: And on the clarinet playing, it's, you know, aside from the Jewish thing, there's a lot of the Epert sound in there, and there's also a bunch of Charlie Parker in there if you listen. It's funny, âcause after we did this, you know, we felt like anything else we could do, would just pale. We felt we did what we were supposed to do, and that anything else would just be, you know, superficial, so we just left it and that was it, âcause we'd originally had intended to record a few things, but this was so strong, we just left it.

Jo Reed: Left it as is.

Andy Statman: Yeah, yeah.

Jo Reed: Where is your musical curiosity taking you now?

Andy Statman: You know, there's a lot that goes on, and there's not enough time.

Jo Reed: How true.

Andy Statman: Yeah. So, I mean, I just find that, for myself, when I start playing, all these ideas come out, and extensions of my own language, which I record, and then I want to go back and learn so there's a backlog of that. I'm teaching at mandolin camps, and

I'm sort of revisiting some mandolin players who I listen to occasionally during the year, who are big influences on me, and relearning some of their stuff to teach it, and, you know, reconnecting with a lot of those feelings and those ideas and those ways of approaching music. And at the same time, you know, I always listen to Charlie Parker, and I've been very interested in writing songs in the older, fifties rock-and-roll style that we play with- with the band, you know? And I've been sort of revisiting a lot of the old rock-and-roll saxophone styles, not the, like, just Junior Walker and King Curtis, but anonymous guys on Del-Vikings records, and things like that. And particularly on YouTube, there's a tons of stuff, they're really classic blues solos or extensions of blues solos. These guys could the good ones could really play. They're really basically coming out of, you know, swing and the big bands and some bebop, but they put it in a certain type of way, and it's just an incredibly fun and uplifting and beautiful way to play blues. So I've been sort of re-exploring that, particularly using it on the mandolinâ¦

Andy Statman: And also listening to people like, you know, old Gene Vincent things and stuff, and there's an energy in- in that early sort of rock-and-roll, rockabilly, you know, that's absolutely incredible, super intense and really great. So I've been starting to write some songs influenced by that, and doing them with my band. Also I've gotten very interested in the way just sort of you know of jazz from the twenties and thirties, the way some of those solos are con- are constructed, and their use of arpeggios and things like that, and I'd- I'd always been more bebop-oriented, but, you know, there's such great color and creativity in the way these guys play. It's really amazing, and so I've been fooling around with some of that language, and you know, I'm not interested in playing that music as playing that music, but using those ideas as- as part of the the well for my own music?

Jo Reed: You teach, as you said mandolin camp, what do you try to impart to your students?

Andy Statman: You know, on mandolin, you know, and on clarinet. I mean, the first thing I try to do is to get these students to realize that we're all equals, and that some may have more talent, some may have less, but it's all sort of practice, and practice is all desire. In other words, if the music moves you, then you'll have the desire to practice. And someone who may be supposedly less talented, but really practices, will eventually be more successful than someone who's maybe very talented and doesn't practice. I also try and make them realize that, don't worry about mistakes. You know, we're not computers. I tell them that when I play a gig, if I start a song and I know it's not happening, I'll just stop it. And, you know, I say, "Well, you know, I'm not playing music to torture myself for the next five minutes. You know, if it's not happening, forget it, you know, and move on to something else, you know? If you make a mistake, you make a mistake. It doesn't matter." I try and give them a real basis for relaxing in their playing, and that, I mean, I try and do that continually. And then, in terms of mandolin, we might be working on certain stylistic things. But I try and get them into the spirit of the music and what the music is saying, and how to sort of make it their own, and how to get behind their own ideas. In terms of, say, klezmer music specifically, at this point, you know, I've come to feel it's uh.. klezmer, unfortunately, is, since it's not part of a living community, so to speak, there's no such thing as "quality controls." So it's a style that- that- that can be sort of hinted at, but not really played, and people will think you're really playing it. It's a style that's very easily sort of invoked, but not really played. There's a way to do it and there's a way not to do it, and this is what I learned from Dave Tarras. And I sort of feel a responsibility to teach my students how to really play it, you know, and that's sort of a time-consuming way of doing it. The way to teach it is time-consuming, but everyone gets inspired by it, and they really learn how to do it. But it's a slow process. So with traditional Jewish instrumental music, I'm looking to convey a literacy in that music, a grammatical and emotional literacy, as well, in terms of mandolin styles, but overall, to try and have the musician feel some sort of self-confidence in their own ability to be able to play what they want to play, and nnot to worry about all these stupid little things, not to feel pressured. Of course, I tell my students, "The reason we're all playing is because it makes us feel good." And what can happen very, you know, of on- very early on is that you become a prisoner of technique and a prisoner of the music business. And then, you know, you sort of have no musical identity. You'll just play whatever people want you to play, and, you know, what's... you know, we all know great, great technicians, who, if you ask them, "What do you really like to play," they'll say, "What do you mean?" The music it's just something they do.

Jo Reed: It's a job.

Andy Statman: It's a job, yeah.

Jo Reed: Well, no one can say that about you, Andy.

Andy Statman: Well, thanks.

Jo Reed: Not at all. So many congratulations.

Andy Statman: Thanks, thanks.

Jo Reed: And thank you for everything you've done.

Andy Statman: Well, thank you.

Jo Reed: Truly.

Andy Statman: Well the truth is, it's really and, you know, it's really nothing, to tell you the truth, so it's, you know, it's just what I do. It's not such a big deal.

Jo Reed: Oh, well. It is for some of us. <laughs>

Andy Statman: Well, thank you. <laughs>

Jo Reed: That was klezmer clarinetist, mandolin-player, composer and 2012 National Heritage Fellow, Andy Statman.

Don't forget to mark your calendar for October 4! That's when the 2012 National Heritage Fellows perform in Washington DC! Along with Andy, honorees include dobro player Mike Auldridge, The Gospel Quartet, The Paschall Brothers, and Tejano accordion player "Flaco" Jimenez. It will be a night to remember!

Go to arts.gov and click on National Heritage Awards for more information.

You've been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Adam Kampe is the musical supervisor.

- Excerpt from "Wedding March" and from "Gypsy Music and Sirba" from the album Jewish Klezmer Music: Zev Feldman and Andy Statman, arranged by Zev Feldman and Andy Statman,used courtesy of Shanachie Records.

- Excerpt from "Flatbush Waltz" from the album Flatbush Waltz, used courtesy of New Rounder, LLC.

- Excerpt from "Maggid," and from "Purim," from the album Between Heaven and Earth performed by the Andy Statman Quartet,used courtesy of Shanachie Records.

- Excerpt of "East Flatbush Blues" from the album East Flatbush Blues, used courtesy of New Rounder, LLC.

Excerpt from "Forsphiel/Improvisation" from the album Awakening from Above, used courtesy of Shefa Records.

- Excerpt from "Old Brooklyn," "Ocean Parkway After Dark" and "The Lord Will Provide" from the album Old Brooklyn, used courtesy of Shefa Records.

All music performed by Andy Statman

Ricky Scaggs is the singer on "The Lord Will Provide" which was written by John Newton, and arranged by Ricky Scaggs and Andy Statman. All other music was composed or arranged by Andy Statman.

The Art Works podcast is posted every Thursday at www.arts.gov. And now you subscribe to Art Works at iTunes Uâjust click on the iTunes link on our podcast page.

Next week, curator Sarah Cash takes us through the American Wing of Washington DC's Corcoran Gallery.

To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

ADDITIONAL CREDIT:

"The Lord Will Provide" used by permission of Heartbound Songs, LLC. (ASCAP)

In part 2 of our conversation with Andy Statman, we follow his musical path as he blends klezmer, jazz, blues, and bluegrass into a distinctive musical voice.