The Medea Project: Where Art and Social Activism Meet

When we spoke last week, theater artist Rhodessa Jones said that a great social worker is like a great artist who chooses humanity as their medium. But Jones is also proof that the reverse is true. Using playwriting, acting, and directing, she has created her own brand of social work designed to empower incarcerated women and women with HIV.

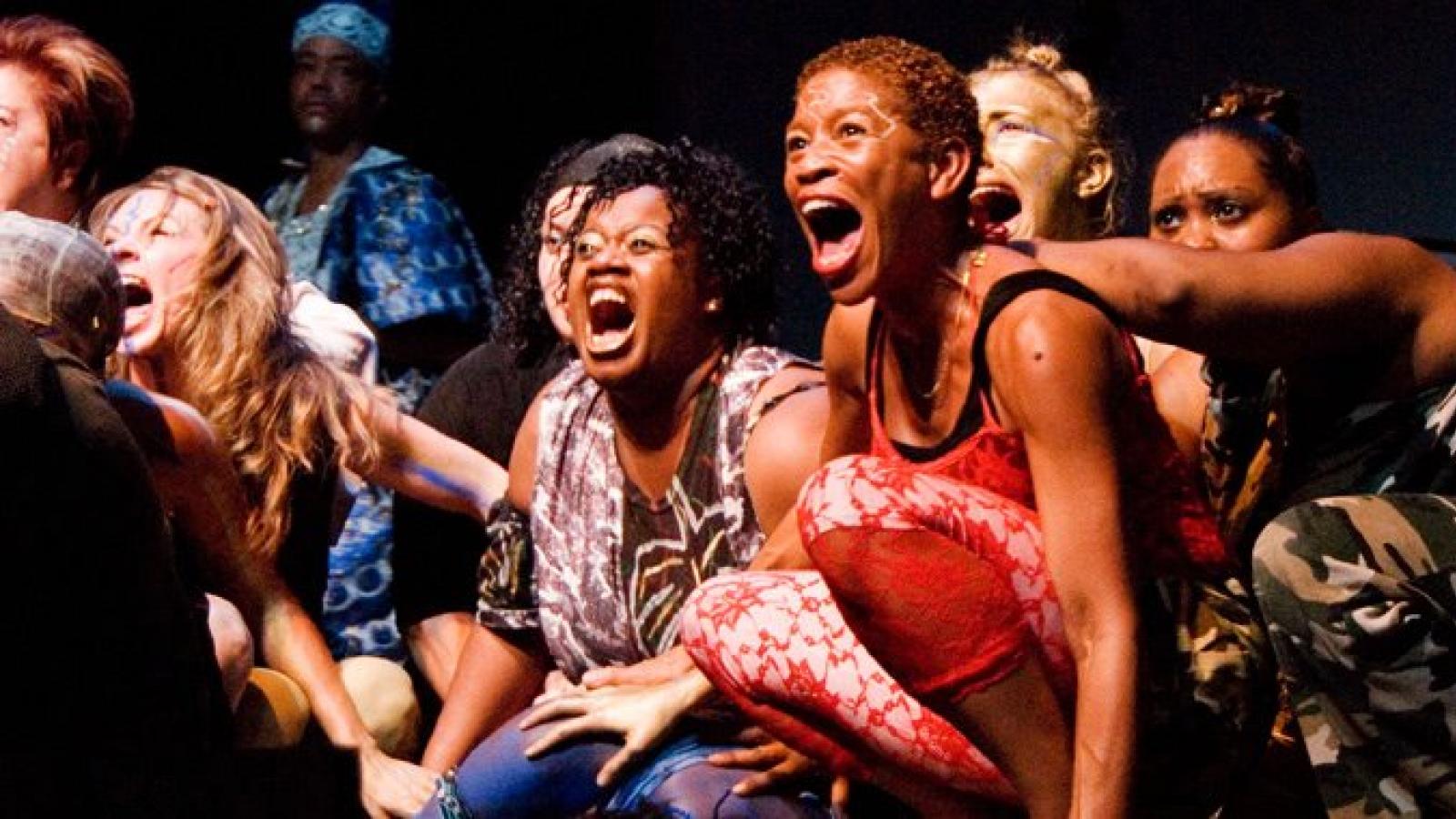

Jones began to work in prisons in 1989 when she was hired to teach aerobics at the San Francisco County Jail. But she quickly realized that she could do more good addressing the needs of their hearts and minds rather than their bodies. She founded the Medea Project: Theater for Incarcerated Women that same year, a program of her performance company Cultural Odyssey, a frequent NEA grantee. The Medea Project works with incarcerated and HIV-positive women in the United States and South Africa, turning their personal stories into dramatic works that they then perform. By having women dig deep into their emotions and memories, Jones hopes they will gain the healing and confidence needed to decrease their chances of recidivism, or simply take positive steps in their lives.

Below, Jones recounts the roots of her creativity, how theater can help marginalized women find their voice, and her views on the relationship between art and social justice.

NEA: You and your siblings are all extraordinarily creative (her brothers include writer Azel Jones and choreographer Bill T. Jones). Can you talk about your childhood and how you became introduced to the arts?

RHODESSA JONES: My mother and father were migrant workers. We had a home in Florida and every year, they would pack us all up in April and we would be gone right through to October. We would travel up the Eastern Seaboard picking vegetables and for us kids, we would all go to these various schools. We were like outsiders in America. I think part of us as communicators and as performers has to do with the fact that we were constantly in and out of different environments, and having to figure out a way to navigate it all.

We used to meet a lot of black vaudevillians who had no recourse but to join this seasonal trek to make money. The theaters were closing; that whole “tough on black asses” circuit was dying. [Ed note: Black vaudeville’s Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA), operated by whites, was sometimes said to stand for “Tough on Black Artists,” or “Tough on Black Asses,” for its treatment of black performers] So these people who had [performed] most of their lives would come to the camps. On Saturday night they would dance and tell jokes and they knew [comedy duo] Butterbeans and Susie, they had been onstage with Louis Armstrong. But now they were just simple illiterate workers because they had not any other education other than the stage. It really helped shape us.

All this was a part of finding your way as an artist. The history of being a black artist in America came from this kind of barefooted, raw, soulful presentation of your skills—tap dancing, singing, singing in harmony. All of this shaped who we were. And then in the 1958, 59, my father made the decision to stop traveling up and down the road because my mother was very concerned about us getting a full education. And for them, that was simply finishing high school. We were poor and trying to get a foothold, so we were constantly given boxes of books and clothes. We had books before we had television, and I think that too helped shape us as performers and as thinkers, writers.

NEA: You mentioned a few times this feeling of being an outsider. Do you think that has informed your current work with incarcerated women, who are very much on the margins of society?

JONES: I think so. It just made sense to me that I would go into these communities. It didn't frighten me or unsettle me to do this work. I had been a theater artist in San Francisco, so I'd been an artist in all these public places, including schools. In the Mission District where I taught a lot, there were so many different kinds of children. I thought, “How do I get these children to see each other and all of their gifts? How do I get these children to appreciate their differences?” We had show and tell, and I would have the children bring in their grandparents. Then the grandparents started to bring in food from where they came from. All of a sudden the children are having this exchange—a culinary exchange, a cultural exchange, a musical exchange. It was stunning, and it just made sense to me. Again, it's back to how America has become a melting pot of all the outsiders.

That's how I got an invitation from the California Arts Council to go into jails and teach aerobics, because they had heard about my work with children around the city. That's how it all began with the Medea Project. All of a sudden I was in jail with all these women—there are so many women in lockdown, again from so many different places. They weren't interested in aerobics, but they were interested in storytelling. It was a device to get them to listen to each other, to share their stories of where they'd been, as well as taking them back to a place before they were a number, or a criminal, a prostitute or a paper hanger, even a murderer. It was getting them to go back to a place before life hurt.

NEA: How did your work in South Africa develop?

JONES: I turned 50, and I wanted to talk about menopause in America. I wanted incarcerated women to talk—let's share this phenomenon of insomnia, night sweats, memory loss. So the women in lockdown started to share their own experiences with menopause. Out of those intense conversations, which were wonderful—they were raucous and funny and sad—a lot of women shared that they were also HIV-positive. They were facing 50 and they were lockdown and all their children were in lockdown, because they [as mothers] hadn't been around. I did a piece entitled Deep in the Night on menopause and insomnia and night sweats and HIV. I did the piece at the Yari Yari conference [an international symposium of female writers] at NYU in New York. There was a woman there named Roshnie Moonsammy from Johannesburg. She came up to me, and said, “If I can arrange the money, can you come to South Africa?” I said, “Sure!” I wanted to find a way to reach out and touch the lives of women who are incarcerated in South Africa. She got me a couple of workshops in the prisons, and therein began this long relationship with the prisons in South Africa.

NEA: How is the culture of incarceration different in the United States and South Africa?

JONES: In America, I think that the powers that be saw that women suffer such depression. They eat garbage, there's too much sugar, and women are simply labeled as “bad girls.” When a woman is in labor, she's taken to the hospital in chains and handcuffed to a bed. I remember seeing that for the first time many years ago and I said, “This woman's in labor. She's not going to run, trust me.” They just looked at me like I was an artist, so what did I know? Some of them were babies—they were young women themselves—and they were terrified, sad, disappointed. Now you're having your first child or your third child in prison, they're going to take this baby away from you, and you're going to go back to doing the rest of your time.

In a prison in South Africa, you will be dealing with at least seven different languages, and English. The jailers are usually black, largely. There's a sense of unity, there's a sense of kinsmanship that the jailers have in South Africa [with prisoners] that I have not felt here. I feel like black folks here suffer such self-loathing that we're harder on our own people, the people who look like us. Whereas in South Africa, they even have something called Culture Day that happens three or four times a year, when everybody is allowed to put on their native costumes, dance, and eat food from their respective communities. The jails are very decrepit, they're very old, but there's much more of a sense of humanity, at least in the women's prisons.

The prison industrial complex is becoming big business here in this country. It's not about people being rehabilitated. We still don't know what to do with prisoners, and we really don't know what to do with women prisoners. In California at any rate, [former San Francisco Sheriff] Michael Hennessey was very supportive when I came on board, because he felt like art maybe was the last frontier. If there was a way to use art to get people to open up and talk, to move, to sing, to seek redemption, forgiveness, then he was all for it. I was very lucky that I came in on his watch.

NEA: How do you see participants change throughout the program?

JONES: Women must have voice. You must be able to say, "This happened to me. This hurt me.” I had a project for a while called Baby Medea. It [worked with] the daughters of incarcerated women, and created a “No” chorus. So a little girl learns early that it's okay to say no. Yell, fight—it's okay. Yell loud and hard. I've met women who ran away at 12, 13 from abusive situations they were living in, and still they're looked at as criminals. But if I meet them, I say, “If you can tell me what happened to you, let's look a it. You were right to fight for your life; you have a right to your life.”

It's about self-determination. They'll arrive at this place and say, “I don't want to be doing this anymore. I don't want to be a crackhead anymore; I don't want to be a prostitute anymore.” In the processes, you have to do a lot of writing and a lot of soul-searching. I'm no day at the beach. I can be a pretty hard nut. And the ones who can hang learn a lot from it.

NEA: Do the women write their own plays?

JONES: Yes. They write, and then my job is to direct and put it all together. We’ve dealt with the ugly duckling, we've dealt with Persephone and Demeter, we've dealt with Sisyphus. Greek mythology has always been great to throw out and tell stories and then get women to hang their own experiences on the same premise. Then they start to write. It could be anything from “If you could change your life, what would you do?” to “Who loves you?” to “What is love?” “When was the last time you saw love?” I have a whole list of autobiographical questions. Then I have another list of questions for women with HIV: how has being diagnosed changed your erotic approach to relationships? How has it changed your sense of self? In Africa, it was a lot about how we put ourselves in harm's way. It was very interesting because when I first went into the prisons in Africa, I said we're going to write letters home, we're going to write on a particular subject matter, and we're going to write to our children, we're going to write to our families, we're going to write to our churches. They all understood. One young woman said, “You mean we're going to write like Papa Mandela?” It just filled up my heart that they already had a signpost. And I have bushels of writing. One of the best exercises I have is “What is it that you need to know about me?” It gets you to look at yourself. That's been a really interesting exercise. Another one is “How do you honor yourself as women?” We're up against a lot out here, so how do we honor ourselves?

NEA: How do you view the relationship between the arts and social activism?

JONES: I think the arts are the last frontier. Art is supposed to shake things up. Art is supposed to set up a series of questions and quandaries. As my friend Shawn would say, to be a great social worker is to be a great artist—an architect of humanity. I feel like being an artist is about finding ways to ennoble our humanity. It's about finding ways of opposing those questions that are painful, that are hard. At the same time, the real genius is how do you make it as universal as possible.

Art to me is a lot of examining, pursuing, deconstructing ideas. Some of them have already been thought about, some of them are new for maybe me, but there is always some gold in these hills, there's always some rough diamonds to be exploited, to be shared with a community.

The Medea Project itself is a very popular theater project for the community. I think it has to do with people wanting to come out and hear the stories because we live with such shame, and such stigma. My first big project with women with HIV was named Dancing with the Clown of Love. I did the project and then I opened it up for questions at the end. There were people that came out in that audience about their status. They came out and said to a community of people, "I have HIV, and I’ve been hiding all these years." The work is largely the private made public, which to me is a large part of what social activism is. It gives other women permission to claim it, to claim the lion that's in you. You want to come for me? I've already told you the truth now so there's nothing you can drag through the mud about me.

Art for art's sake is fine. I don't have time for it. I think art should save lives on some level. It's about moving us all forward. How can we as a community be inspired by the arts, by the stories of incarcerated women, by the stories of women who are living with HIV? How can we share this with our daughters? Somebody's child needs to hear this. I hope there ends up being joy and jubilation, that's good, but it's scary and dangerous out here, and we must be the ones to tell our daughters and our sons.