“I believe that folk and traditional arts speak to family and community, intergenerational transmission of knowledge, and shared language, culture, and history. What I find fascinating about these forms is the sheer vitality and, all too often, fragility you encounter when in their presence ...” – Sabrina Lynn Motley

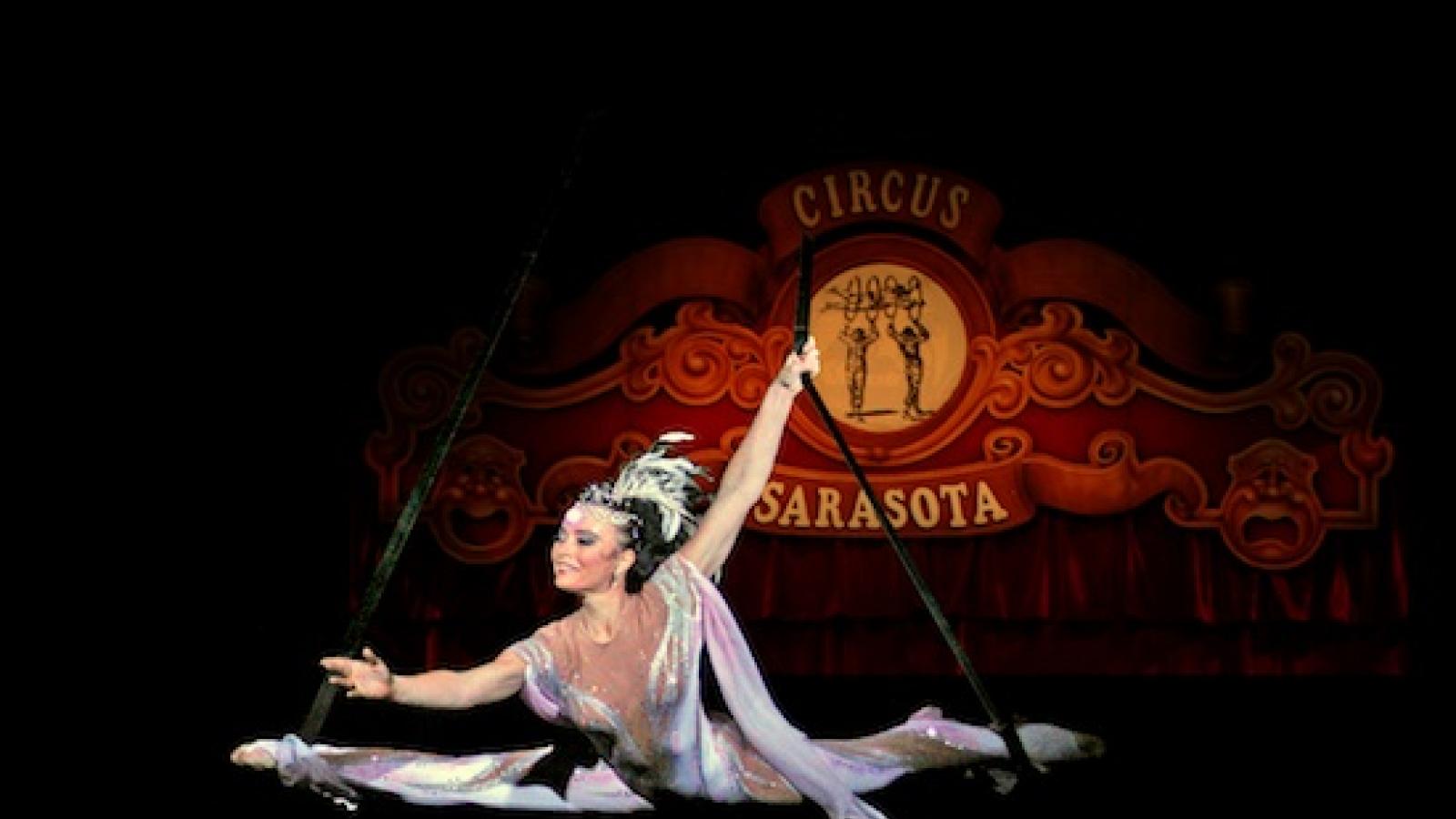

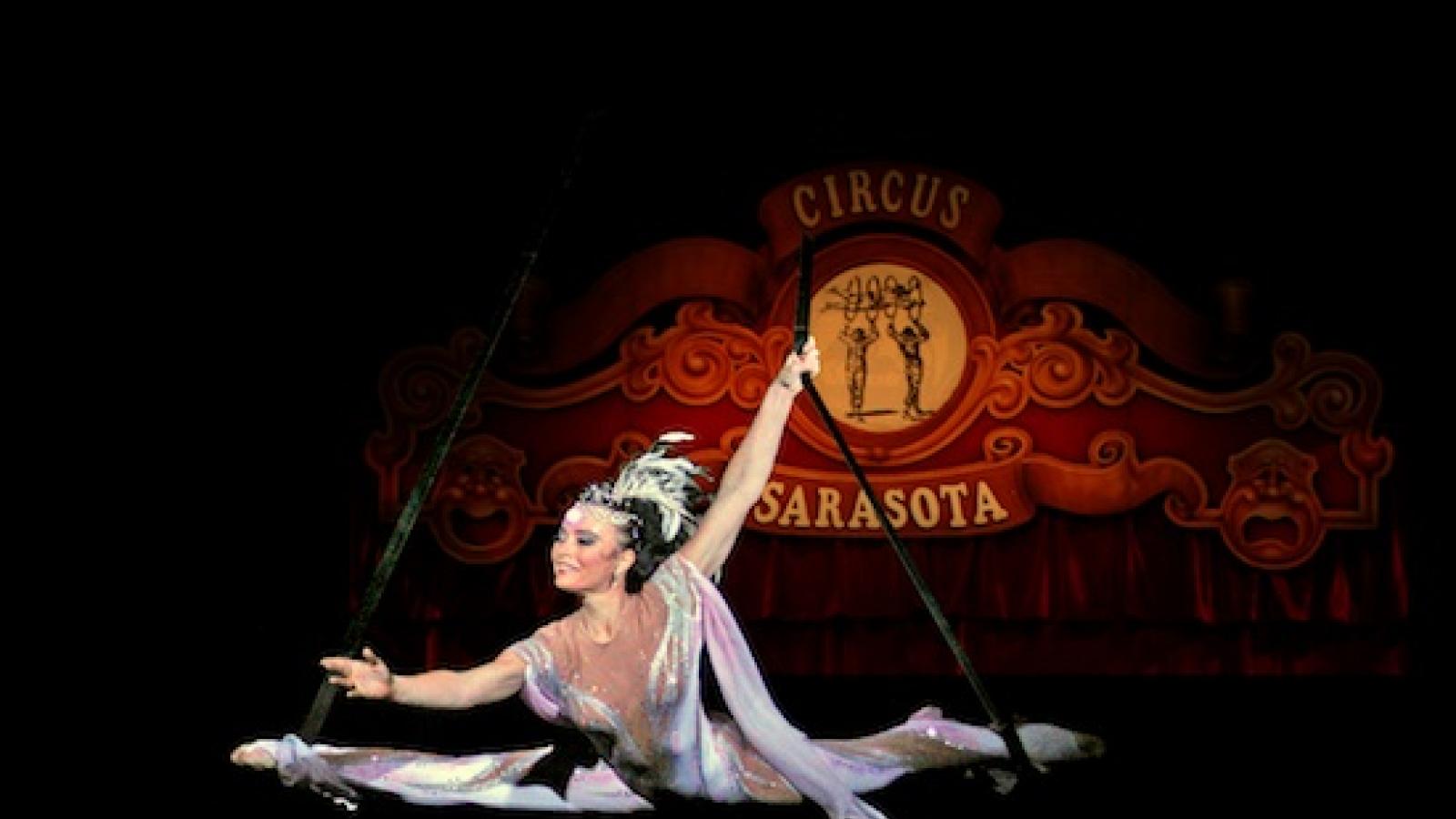

When you hear the word circus, what do you think? Clowns, trapeze artists, parading elephants, and the like no doubt. And while the circus arts are definitely about spectacle--we dare you not to catch your breath when Heritage Fellow Dolly Jacobs performs one of her breathtaking aerial stunts--they are also about tradition, community, and apprenticeship. In other words, glitz and glitter aside, the circus arts belong on the family tree of the folk and traditional arts. To learn more about the centuries-old art form as well as about contemporary understandings of circus, we spoke with Smithsonian Folklife Festival Director Sabrina Lynn Motley.

NEA: The term "folk and traditional arts" comprises a large diversity of art forms. What is it that defines a folk and traditional art, or allows an art form to fit into that category of arts?

SABRINA LYNN MOTLEY: One of the wonderful things about working at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Culture Heritage is that we have a mandate to wrestle with this question day in and out. Our work has meaning because we are able to do so in collaboration with an incredible diversity of artisans, musicians, dancers, researchers, policy makers, and more from around the world. Like so many others, including the NEA, I believe that folk and traditional arts speak to family and community, intergenerational transmission of knowledge, and shared language, culture, and history. What I find fascinating about these forms is the sheer vitality and, all too often, fragility you encounter when in their presence (as performer, audience member, researcher, and/or presenter). Of course, all of this becomes more complicated when considering the place of/for more recently developed forms of expression. Hip hop is an obvious and frequently referenced example, but there are so many others. This is why the question will remain an open one. That’s a very good thing.

NEA: How do you define the circus arts, and how do they fit into the folk and traditional arts?

MOTLEY: A few days ago, I had a conversation with wonderful people at American Youth Circus Organization. They posed a similar question, “where do we sit alongside other art forms,” so I’ll take my cue from them and respond first to the last part of your question. If we agree that folk and traditional arts include the qualities mentioned above then circus arts tick all the boxes. For example, I’ve been struck by discussions about changes to the transmission of knowledge and practice. By no means have multigenerational circus families disappeared, but circus schools have become increasingly important sites of exchange. These schools and programs, which exist in every state in the union by the way, provide an entrée for those born outside the traditional circus family structures.

According to research conducted by our curators, “circus arts” describe several clusters of both performance and material arts that have evolved over time and that have come together to create the spectacles described generally since the mid-18th century as “circus.” Circus performance arts have focused primarily on various aspects of physical movement, strength, and endurance and the ranges possible for the human body and physique. Circus-related material arts include aspects of painting and drawing, design, costuming, and tent making, as well as several derivative arts inspired by the circus such as toy making and miniatures. However, it should be noted that there is no single universally accepted definition of the term “circus arts”, which makes the field particularly rich and interesting (particularly today when heritage factors also are examined and taken into account).

I’m not hedging, but in the end I think that defining “circus arts” is best left to those who live and practice it. What is exciting to many about this period in circus history are concerted efforts being made by performers, scholars, journalists, and others to pull back the tent flap. Doing so will allow those of us in the audience to have a deeper understanding of what the world of circus arts is.

NEA: As you’ve already mentioned, one of the hallmarks of a folk/traditional art is that there seems to be a deep connection or rootedness within a community. How does that manifest with the circus arts?

MOTLEY: As a complete outsider, I’ve found this notion of “rootedness within a community” to be extremely interesting when applied to the circus arts. So on the one hand, performers speak very clearly about what that means in their own traditions. You find these beautiful reflections on communities of practice by clowns, aerialists, jugglers, and so on. On the other hand, you have stories of audience members in communities who speak to the importance of the circus visit. The curator Deborah Walk at the John and Mable Ringling Museum told me that the late Maya Angelou had a soft spot for the circus. Who knew? Growing up, it was one place where entertainment was made and presented equally for and to children of all backgrounds. A lot of those performers were new immigrants themselves. Imagine their experience crossing this country during a very turbulent and painful time in our social history. This, too, complicates our understanding of how communities connect. I won’t overstate the case of circus as an equalizing site, but it is a story echoed throughout the segregated cities in the American south and north.

Here, “rootedness in community” takes on other layers, just as it does when looking at circus schools. They, alongside both independent and corporate troupes, have been at the forefront of what is called the “social circus.” It’s where circus, community, and social engagement—activism for some—intersect in resource-poor neighborhoods, hospitals, after-school programs, and the like. Take a look at circus-making efforts in Ferguson, Missouri. Look, the circus is about possibility, which is a big part of its appeal and its ability to flourish in difficult terrain. Long story short, the very idea of community is a complex one and not easily answered by focusing on place, although cities like Sarasota, Florida, and Peru, Indiana, certainly must be recognized as important capitals of circus.

NEA: I think many people are familiar with the circus arts through Cirque du Soleil or Ringling Bros. Is that the same kind of circus as when we're thinking of the folk and traditional arts? Is there a spectrum?

MOTLEY: Again, as someone outside looking in, this is a tricky question. There is an entire generation of young people who will grow up equating circus with the theater of a Cirque du Soleil. This reflects change, which we all know can be difficult. These shifts have also fueled many to shine a bright light on what rightly can be called “circus heritage arts.” It should be noted these heritage arts also exist within large corporate circuses like Ringling Bros. In any case, it would be a mistake to think that the push to know circus deeply is being done out of desperation. This is an acknowledgement and celebration of a past that in many cases is quite alive in this present moment. Still, like so many other folk and traditional forms, vibrancy and fragility sit side by side. So yes, there is a spectrum, but like any other spectrum we need to have a clear picture of the parts that comprise it in order perceive it correctly. Here, again, I turn to people like [2015 NEA National Heritage Fellow]

Dolly Jacobs who through performance and advocacy, teaching and mentoring give needed definition to circus heritage arts.

NEA: What's the most important thing you want people to know about the circus arts? What myth (or myths) do you want to dispel about the circus arts?

MOTLEY: I was a museum-obsessed kid. As a child, circuses made no sense to me. I’ve learned that many people as children have complicated relationships with the circus and, like me they wind up being completely charmed by it as an adult. The attraction is not only to spectacle, although I am hardly one to deny the power of spectacle. Somehow all of that registers differently as one gets older. Anyway, I think a large part of the appeal has to do with the very things that make folk and traditional arts meaningful: diversity of forms, multiple avenues for skill and knowledge transference, that wonderful “rootedness in community” mentioned above.

Look, stories are the real take-aways. I’ve heard of a famous high-wire walker who only lets his mother make his shoes. What a poignant image! As children we routinely put our lives into the hands of our parents. He continues to do so in such a literal way. Stories like this tell us about the continued role of family in circus life. Then there are the skills are required to erect tents. Mental and physical acumen is a must. Dolly Jacobs and Pedro Reis at Circus Arts Conservatory have a program in which math and science are taught through the circus arts. This is life work. I hope that Dolly’s Heritage Fellowship raises awareness so that people take their seats with a greater sense of what lies at the heart of circus.

Of course, all of this makes circus arts perfect fodder for the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and it will be a signature program during the 2017 season when we celebrate our 50th anniversary. Program curator Preston Scott and program associate Jim Deutsch are working with a team of collaborators who share the goal of promoting circus arts as heritage, folk, and traditional forms. They envisage a space where visitors encounter story and spectacle. We provide a beautiful platform on the National Mall for this to occur, but the dispelling of myths, the answering of tough questions, and the sharing of deep knowledge is the hard graft of Festival participants. Of course, being able to encourage visitors to learn to juggle or maybe fly through the air with the greatest of ease will only make the work all the sweeter.

Did you know that you can catch the 2015 NEA National Heritage Fellowships Concert live even if you're not in Washington, DC? Just tune into the livestream on arts. gov. More details here.